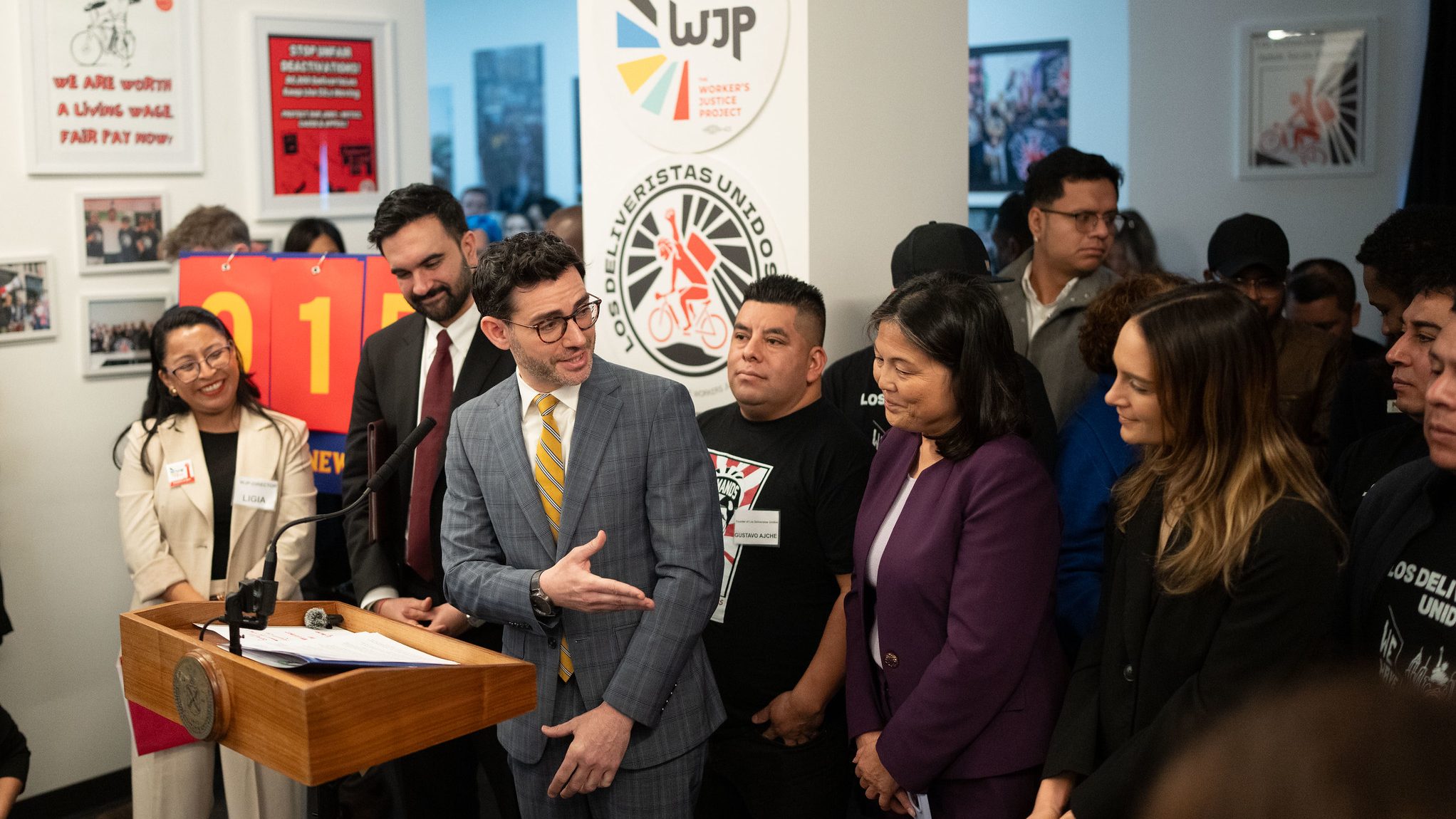

The Department of Transportation must redesign the city’s truck routes for safety and environmental justice, a move that could reduce the number of gas-guzzling big rigs that currently disproportionately roll through low-income communities of color, leading to increased asthma, cardiovascular disease and road violence, pols and advocates said on Monday.

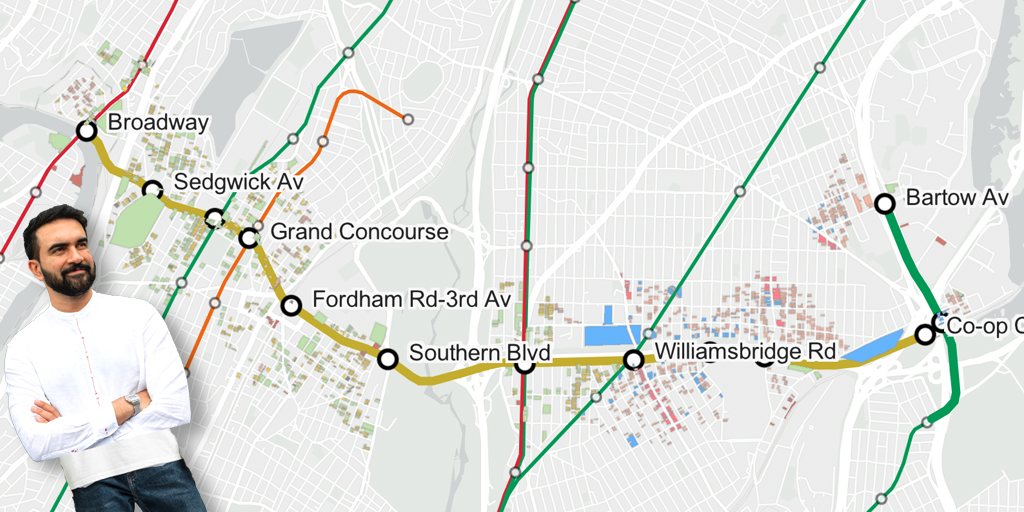

The current truck route map — comprising about 1,300 miles across the five boroughs — has remained largely unchanged since the 1970s, though DOT said it made “minor edits” in 2015 and 2018. A bill, Intro. 708, introduced on Monday by Council Member Alexa Aviles (D-Sunset Park) would force the agency to do a complete overhaul.

The DOT said it supports the bill.

“The current situation is already problematic,” said DOT’s Eric Beaton during an oversight hearing on Monday. “We know we do need to make changes. The trend in recent years has only been in one direction, up and up. We want fewer truck miles on our streets."

Beaton added that the city does not support the portion of the bill that would mandate daylighting at each intersection adjacent to the truck route network.

“We don't think a blanket policy is appropriate,” he said.

Truck deliveries skyrocketed during the pandemic with the rise of e-commerce — more than 80 percent of New Yorkers receive at least one package each week, and 18 percent receive packages at least four days a week, according to DOT. Those packages are delivered on an average of 120,000 trucks a day, carrying 90 percent of the city’s goods, with that number expected to rise over the next several years. Just eight percent of the city’s goods are transported by water, DOT said.

And the explosion of truck deliveries — coupled with the rise in distribution warehouses like Amazon, FedEx, and UPS in neighborhoods where property values are lower — has been a burden on communities like Sunset Park, Red Hook, and sections of the Bronx and Queens.

"Since the pandemic, the communities that I represent ... have experienced a rapid proliferation of last-mile logistics facilities flooding our streets with massive uptick of traffic and air pollution in what was already an environmental justice community," said Aviles during a rally outside City Hall ahead of the hearing. "We must take action."

And what makes matters worse is that highways like the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway cut through such neighborhoods.

“Last-mile facilities bring increased traffic to residential areas with narrow streets that are not designed for these uses, worsening air pollution, high asthma rates, health concerns, congestion and pedestrian safety issues,” said Sarah Elbakri of UPROSE during the rally. “These mega facilities exacerbate the cumulative impacts of the Gowanus Expressway, and BQE and other public infrastructure that have been historically cited in communities like Sunset Park.”

DOT last week unveiled a pilot program featuring 20 “micro-delivery hubs” around the city, where designated curbside areas will be set aside for truckers to unload packages, which will then be delivered by cargo bikes or other small vehicles.

In 2019, then-DOT Commissioner Polly Trottenberg cited gentrification in industrial zones and the mixing of trucks and bikers as a major reason for rising cyclist deaths.

And in 2022, 42 out of the 258 total road fatalities involved trucks and 68 percent of injuries took place on truck routes, according to DOT.

Several recent high-profile fatalities involved trucks, including the death of 28-year-old Carling Mott, who was killed by the driver of a tractor trailer on E. 85th Street in July 2022; 37-year-old Sarah Schick, who was killed by a truck driver on an unprotected portion of Ninth Street in January; in March, 56-year-old Eugene Schroeder was killed by a truck driver in Williamsburg; last October, Kala Santiago was killed by a truck driver on Parkside Avenue; 35-year-old Alfredo Cabrera Liconia, who was killed by the driver of a massive Bud Light truck near a new protected bike lane on Crescent Street in Astoria in 2020.

All those deaths — and so many others — highlighted the dangers of trucks mixing with cyclists and pedestrians, and the question of whether the big rigs were even allowed to be on those streets.

When we ask @NYPDTransport to enforce oversized trucks, it's not some kind of abstract concern. I just saw this situation @nypd78pct yesterday. It's not a fair match-up. In fact, it is deadly. They need to be prevented from exiting the highway in the first place. https://t.co/HlUn2igfPr pic.twitter.com/WirKAFN0fj

— Joanna Oltman Smith (@jooltman) July 27, 2022

In the Astoria incident, a sign forbids truckers from making a right turn onto Crescent Street, unless for a local delivery — which is what cops said at the time that trucker did.

Advocates say that more enforcement is needed to keep illegal 53-foot trucks off city streets, and keep those that are legal on their correct paths.

“We also need to get better and smarter at enforcing truck-route regulations. With advances in navigation technology, no truck should be off route except when using the most direct last-mile path to a delivery or pickup, and we should explore using GPS tracking to enforce violations,” said StreetsPAC’s Eric McClure during his testimony. “We also need to adopt a zero-tolerance approach to 53-foot trailers, with fines great enough to keep them off city streets, period.”

For its part, the Trucking Association of New York said it supports a redesign of the network — and daylighting.

"The truck route network is a key safety tool, and we must ensure trucks stay on route,” said Zach Miller, the association’s metro region operations manager in his testimony. "Lastly, we are happy to see an emphasis placed on daylighting at intersections adjacent to the truck route network.”

In addition to the truck route redesign legislation, the council is also pursuing Intro. 906, which would require the city to identify one location in each borough that could be designated off-street parking for tractor trailers by the end of this year, and create such parking by the end of 2025; and Intro. 924, which requires the Department of Transportation to study street design as a way to limit or reduce the use by commercial vehicles in residential neighborhoods.