They should have known how dangerous New York City streets are!

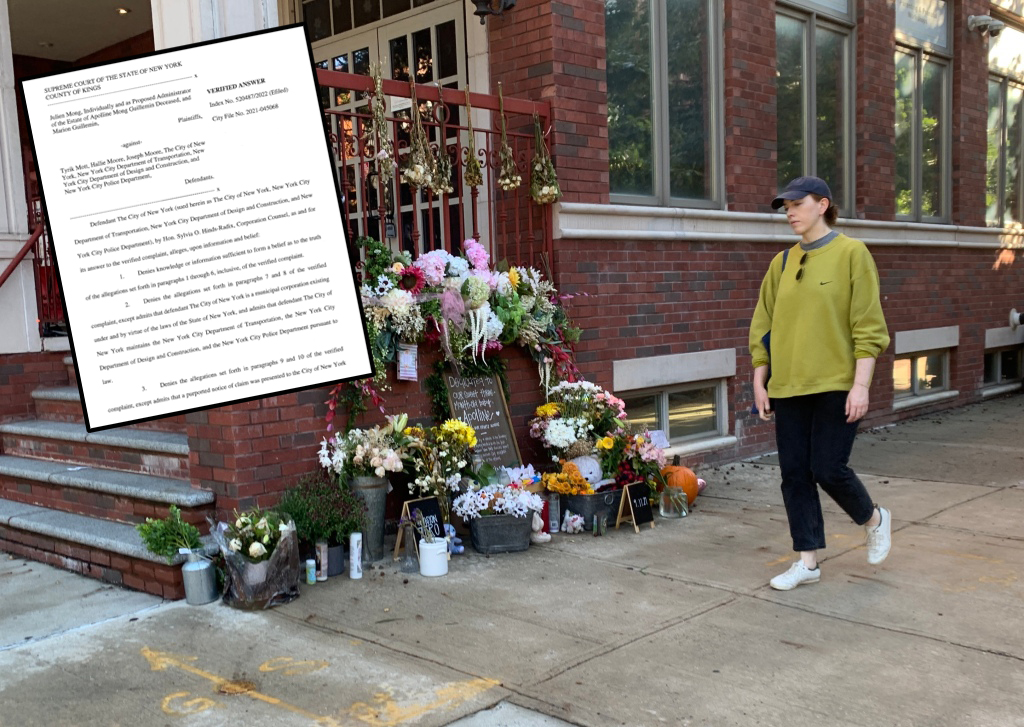

In a particularly painful example of victim-blaming, the city is arguing in court that the parents of Apolline Mong-Guillemin "caused or contributed to" the death of their 3-month-old baby when a reckless driver who never should have been on the road crashed into another car before both fatally struck the child and injured her mother on the sidewalk.

"Plaintiff[s] culpable conduct caused or contributed to the alleged injuries and the alleged wrongful death," the city's Assistant Corporation Counsel Elizabeth Gross wrote in court papers filed late last week in response to a wrongful death lawsuit filed last month by Apolline's parents, Julien Mong and Marion Guillemin against the city and the drivers involved in the crash. "Plaintiff[s] negligence caused or contributed to the alleged injuries and the alleged wrongful death."

And after blaming both parents for "negligence" and "culpable conduct" for taking their daughter for a walk on the sidewalk along Vanderbilt and Gates avenue in the gloaming of Sept. 11, 2021, the city twists the shiv a bit deeper by claiming that the parents should have known how dangerous it is to walk along a New York City street — a legal argument that at once seeks to hold the city blameless while also admitting that it is failing to keep the streets safe.

"Any and all risks, hazards, defects, and dangers ... were of an open, obvious, apparent, and inherent nature, and were known or should have been known to plaintiff[s]," the city's court papers claim (read them in full below).

"It's beyond offensive," said the Mong-Guillemin family's lawyer, Harris Marks, an attorney at Belluck and Fox. "As attorneys, we have an obligation to not make frivolous claims, and in my opinion, saying that Julian Mong or Marion Guillemin are negligent or had anything to do with the death of their child because they were standing on a sidewalk is offensive and should be withdrawn. The city knows it's absolutely not true, but they put it in there anyway."

The Mong-Guillemin suit specifically blamed the city for failing "to design, construct … and maintain [roads] in a reasonably safe condition thereby creating dangerous and hazardous conditions.” The city was warned in the past that drivers sometimes drove the wrong way up Gates Avenue as a shortcut to Vanderbilt, as driver Mott allegedly did as he fled cops before slamming into a car belonging to Hallie and Joseph Moore, who are also named in the suit.

The suit also blames the NYPD, whose unidentified officers “acted in wanton disregard in their unsafe pursuit of Mott’s vehicle for running a red light” prior to the crash. “Defendants engaged in pursuit when circumstances warranted discontinuance, and failed to adhere to the NYPD patrol guide.”

“The risks to the public,” the suit continues, “outweighed the danger to the community if the suspect was not immediately apprehended.” (Mott was still driving even though his car had been slapped with 106 camera-issued speeding and red-light tickets since 2017 — and he had driven with a suspended license.)

The city papers argue that the Department of Transportation can't be held responsible for roadways that it fails to redesign for safety.

"The City of New York is immune from suit," the court papers argue, because its actions "involved governmental planning decisions undertaken with adequate study and a reasonable basis, and/or the exercise of discretion in the performance of a governmental function and/or the exercise of professional judgment."

Gross's paperwork even absolves the NYPD for the alleged chase that preceded Mott's mad dash before he slammed into the Moores's car, which careened into the Mong-Guillemin family.

"The actions ... were tactical police decisions involving the governmental exercise of professional judgment and discretion, and defendant ... is immune from suit," the papers say.

Lest anyone believe that the city holds the Mong-Guillemin family fully responsible, the city does affirm, "Any damages allegedly sustained by plaintiffs were caused in whole or in part by the actions or omissions of defendant Tyrik Mott, Hallie Moore, and Joseph Moore."

As egregious as the victim-blaming sounds in these court papers, such language is standard in wrongful death cases against the city. In 2020, when the family of an architect killed by falling debris sued the city, the Law Department blamed the victim for doing something virtually every New Yorker does every day — walking on a sidewalk.

“Plaintiff(s) knew or should have known ... the risks and dangers incident to engaging in the activity alleged," the city Law Department wrote, according to the Daily News, which pointed out that the “activity alleged” was walking on a sidewalk.

And if that wasn't blamey enough, the Law Department's counter-claim also blamed the victim for failing "to use all required, proper, appropriate and reasonable safety devices ... to assure his/her/their safety.”

For the most part, the city's court papers in the Mong-Guillemin case seek to avoid putting any culpability in writing. Instead, virtually all clauses in the city's papers begin with a blanket denial of the corresponding paragraph in the family's lawsuit. Sometimes, the denial of guilt adds in language that seeks to put off a real discussion until all parties are before a judge.

"Allegations that are conclusory and evidentiary and present questions of law and fact should be reserved for decision at the time of trial," the city argued.

In other words, we'll see you in court.

Julien Mong v Tyrik Mott Et Al Answer With Cross c 5 by Gersh Kuntzman on Scribd