The Council member representing McGuinness Boulevard slammed the Department of Transportation for an "inadequate" preliminary redesign of the highway-like roadway, where three people have been killed since 2014, including a beloved teacher whose hit-and-run death finally convinced the city to act.

"I'm really quite disappointed in the Department of Transportation and the presentation this evening," said Council Member Lincoln Restler, adding that local elected officials, including Assembly Member Emily Gallagher and Borough President Antonio Reynoso, have been calling for the elimination of one of the two travel lanes to slow down cars and reduce crossing distances on the wide road. "Really, go back to the drawing board and take a much harder look at how we can make this street safer."

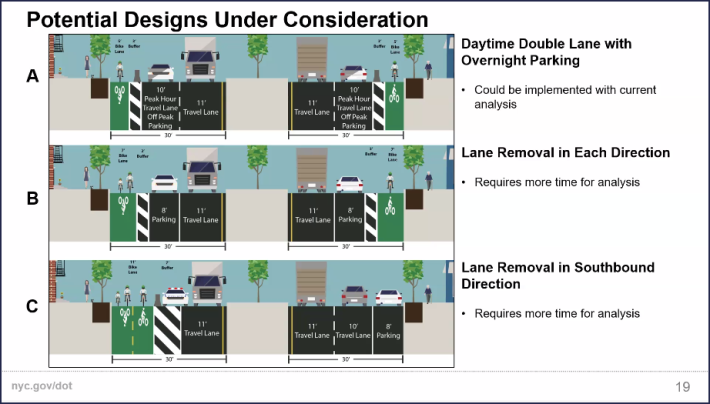

Restler's comments came after DOT presented three preliminary options for the roadway and truck route that connects Meeker Avenue and the Pulaski Bridge, is often used as a shortcut by drivers, and where, since 2013, there have been 1,548 reported crashes, injuring 40 cyclists, 59 pedestrians and 236 motorists (basically one crash every other day). The three options included

- Option A would follow a pattern of Second Avenue in Manhattan, where parking is allowed only during non-rush hours to accommodate high vehicle volume. It would add a protected bike lane, but would not reduce the four lanes of traffic, as the local officials want. The parking lane would return at night to narrow the roadway when speeding is most common.

- Option B would remove a lane in each direction and add a protected bike lane on each side, but it would maintain parking, which many supporters of safety believe is the root of all roadway danger.

- Option C would remove a car and parking lane on the southbound side and include a two-way protected bike lane on the west side of McGuinness (the graphic included an illegally parked police car as a serving suggestion).

Supporters of road safety focused on Option B, but the DOT said that it would need to perform additional analysis because in Option B or C, truckers and car drivers would likely use residential side streets to avoid traffic.

In other words: wait 'til next year. The agency said it will consider all the comments — the meeting went on for hours — and would return to the community board this fall, meaning that nothing will be built on the roadway until 2023, two years after the latest reason for the road redesign: the hit-and-run killing of Matthew Jensen in May 2021.

Within weeks of that death, then-Mayor de Blasio pledged $39 million for a major capital renovation of the roadway, with a design to be determined. But the capital plan is on the back burner now — it can't be started until after whatever "in-house" design the DOT ultimately selects. Agency rep Eric Wyche said the "in-house" design would "inform" the capital plan.

Several members of the public spoke out against any option that would remove parking — with one local business owner, Tony Argento, describing parking as a basic civil right.

"They're taking away our parking spaces! It's very unjust," he said.

But others spoke of a different injustice: The danger of a roadway that did not always exist in its current state, but was widened in the 1950s from a quiet neighborhood street to a mini-highway. The result has been disastrous for safety, pollution and community cohesion, many speakers pointed out (Wyche added that the biggest concern of neighbors who were surveyed was the need for walking and biking improvements, and the desire to rein in aggressive driving).

After Argento spoke, Chris Roberti retorted that he's afraid to cross McGuinness with his kids: "We need something more drastic to cut pollution, bring our community together and keep our children safe."

A neighbor, Luke Ohlson, added, "If people's reaction to this is concern for parking and not the safety of kids, that should tell you something." He said he supported Option B, but called it "the bare minimum."

"Come back with something better," he added, citing how parking spaces only entrench car culture for another generation.

Safety has gotten lost in the conversation, added Jackson Chabot, calling for a real "road diet" for the wide boulevard. "The reason we're here this evening is because Matthew Jensen was hit and killed by a reckless driver." Chabot used the rest of his speaking time for a moment of silence for Jensen.

In the end, at issue is whether the DOT will make efforts to reduce car and truck use of McGuinness so that the high volumes that use the roadway can be reduced and the roadway be transformed back to the neighborhood street it once was instead of a shortcut for people driving between the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and the Long Island Expressway. An estimated 30 to 50 percent of the traffic on the road is simply short cut drivers, the DOT said.

DOT said it could find ways to mitigate what it believes will be spillover into local streets by changing the direction of some of them, but would need months to figure out which ones, said Shawn Macias, also of DOT.

Restler was clear where he and Gallagher stand.

"The degree of traffic violence that we experienced on McGuinness is totally unacceptable," he said. "The way we're going to fully connect Greenpoint community and make this this street safer is by having less lanes of traffic. And I'm really disappointed that after hearing so clearly from the elected officials in the community, from many thousands of neighborhood residents signing on enthusiastically to the Make McGuinness Safe campaign that still DOT came forward with this presentation tonight [with] plans that fails to curb it in meaningful ways."

In an unrelated story, the DOT also presented a "bike boulevard" plan for the Berry Street open street, but it came up so late in the meeting, and without warning, that no one was in the mood to consider its advantages, which would be similar to the successful version on 39th Avenue in Queens.

"There is so much in this new plan," said Eric Bruzaitis, the committee chairman. "When I heard directional changes. I don't know. There's so much. ... Honestly, this is not what I was expecting to see tonight." (The DOT did, in fact, set up a workshop on the bike boulevard design in May on Berry Street, committee member Bronwyn Breitner pointed out, but the agenda item only listed the discussion as "a design proposal for the Berry St Open Street.")

The idea would reverse the direction of Berry Street in three places, specifically to capitalize on the fact that more cyclists and pedestrians use the open street now than drivers. Here's the full plan:

The Berry Street proposal comes just two days after the DOT proposed a slightly different "bike boulevard" for Underhill Avenue in Brooklyn, another open street that is slated for experimentation [PDF].