It's time to put the park back in Park Avenue. But how — that's the question.

The city Department of Transportation is moving ahead with its plan to repurpose space from car drivers on the iconic, and once bucolic, boulevard — in some spots, more than doubling the median, to 48 from 20 feet, by cutting one of three moving-vehicle lanes — but advocates are demanding that some of the space be set aside for cyclists.

The median revamp, for which the DOT will issue request for proposal for landscape architects this spring, would transform the puny remaining greenery between East 46th and 57th streets to create "more open, accessible public space for people and businesses in the bustling area of East Midtown," according to Council Member Keith Powers. “The pandemic has already accelerated a movement towards a more pedestrian-friendly experience across the city, and this project is a great example of how shifting priorities can help shape a more enjoyable streetscape.”

The median project comes as the MTA, which runs the trains into Grand Central Terminal, is readying a 20-year project to rehabilitate the tracks under Park Avenue, which will require ripping up the street (which is really just a roof over the tracks). The construction ushers in what many are calling a watershed opportunity to reclaim the median. In 2020, the DOT asked for responses on an array of choices for the formerly wide green strip — including reconstructing what’s there now, expanding the median without changing its uses, installing a promenade with concessions and event spaces or even expanding it still further to include those things plus a bike lane.

The DOT, for now, won't say which of several schemes it floated will prevail in the newly expanded medians, only that the expansion "will help Park Avenue better live up to its name,” said spokesman Vin Barone, directing Streetsblog to a DOT schematic drawing of the project's "conceptual geometry," which showed overwhelming support for expanding the median at the expense of cars. The uses of the median will be governed by the master plan developed by the architect, Barone said, and the costs of the project can't be shared yet.

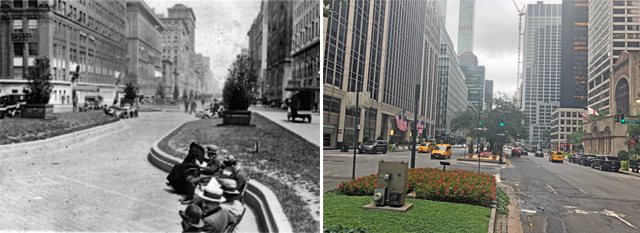

The question of how much car reduction will happen on the avenue is a trenchant one. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Park Avenue had at its center a lovely park that drew pedestrians and promenaders from all over the city, if not the world; the park, with its benches and plantings, was considered a prime New York attraction and drew comparisons to the grandest boulevards of Paris. Sadly, in 1927, the city surrendered much of the greenspace to create another lane for growing car traffic — and the road since has degenerated into a polluted car sewer that is enervating for residents and businesses and dangerous for pedestrians.

Advocates want the full freight — the biggest space possible for people, fully car-free stretches, and a bike lane — because Park Avenue, which does not have buses running on it, can support it.

“Park Avenue is a rare thoroughfare in Midtown Manhattan where planning doesn’t need to account for bus travel or bus stops," said Jon Orcutt, the communications director of Bike New York and a former Department of Transportation official. "We want the city to take full advantage of this to extend a median-side bikeway and improve pedestrian space."

Orcutt said the revamped streetscape should resemble Allen Street on the Lower East Side, a "median promenade and greenway" with "benches, art, movable tables and chairs, events, concession, mall to mall crossings, walkable paths and bike lanes," according to city documents.

Presently, Park Avenue has three car travel lanes and a parking lane on each side of the medians, parts of which are fenced off. Something's gotta give ... and that's car drivers.

“Expanding room for pedestrians while adding in new green space is a great way to reclaim space from cars and make one of New York City’s most iconic streets more vibrant, healthy, and safe,” said Danny Harris, executive director of Transportation Alternatives. Harris added that he hoped that the new Park Avenue would demonstrate the principles of the group's NYC 25x25 plan, which seeks to convert 25 percent of car space into space for people by 2025.

Like other pedestrian projects around the city — those that have transformed parts of Broadway in the Flatiron district, the Financial District, Downtown Brooklyn, and Union Square, to mention only a few — the Park Avenue median project is being pushed and partly funded by private commercial interests, including the local Business Improvement District, the Grand Central Partnership, and Fisher Brothers, an investment firm with offices on the avenue. The trend of business groups spearheading pedestrian efforts is controversial, pitting wealthier areas with BIDs against deserving poor neighborhoods that lack them.

Sometimes, too, businesses' zeal to transform local streetscapes falls flat; for example, a 2018 competition that Fisher Brothers put on to produce innovative designs for the avenue wound up with a bunch of wacky proposals. Fisher Brothers seems determined to pre-empt any pushback against pedestrianization that might arise from the car lobby. It sponsored a survey that found that there is 80 percent less public space per office worker on Park than in similar commercial districts.

“This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to transform Park Avenue’s malls back into the pedestrian enclaves they once were,” said Alfred Cerullo, president and CEO of the Grand Central Partnership, a BID. “Even before the pandemic, East Midtown was starved of much needed open space. By committing to hire a world-class landscape architect, the city has seized this opportunity to invest in East Midtown’s future as we look to build a lasting economic recovery.