We warned him.

Mayor de Blasio promised to reduce his, and his fellow citizens', reliance on cars, but the numbers show that New Yorkers and municipal workers are not doing that.

Hizzoner’s creation of Vision Zero in 2014 called for fewer car trips with the ultimate goal of eliminating all traffic-related deaths by 2024, but one of the most crucial aspects of actually getting to zero — breaking the city’s car culture — has stalled, thanks in part to the Covid-19 pandemic that scared New Yorkers into avoiding public transit.

But the increasing number of cars on the road didn’t start with the pandemic, advocates say. Car ownership under de Blasio — who took years to finally support congestion pricing — has been steadily rising since his very first days in office.

“We’ve been sounding the alarm for years, and are disappointed that Mayor de Blasio did not seize the opportunity to make streets fair and provide more alternatives to get New Yorkers out of their cars," said Cory Epstein of Transportation Alternatives. "The status quo on our streets is unhealthy, unsafe, and untenable."

Well, at least de Blasio doesn't blame himself for leaving behind a city with more cars, and more carnage. He said it's a societal problem that predates him, and he has done his part to address it, like with expanding bus lanes, bike lanes, and creating the citywide ferry system.

"I don't put that one on my legacy tote board there, I just don't," he told Streetsblog at his Dec. 27 press conference. "There's been an explosion of car ownership in general over the last few decades, it's a bigger societal phenomenon. The answer is to create more and more, and better and better mass transit and to discourage car use. I am very comfortable that we did a lot of foundational things, including what we did with busways, Select Bus Service, expanding bike lanes and NYC Ferry. These are all things that are gonna grow a lot more, and are crucial to how we turn around car usage in this city." [The mayor offered a similar comment in Streetsblog's bus analysis, published on Monday.]

Looking inward

Fixing a problem often starts at the top — and for this one, that's means curbing the city fleet that grew during the de Blasio administration.

When de Blasio took office in 2013, the total number of on-road vehicles in the city’s fleet was 23,671. By 2019, it jumped to 25,348. By 2021, the number of on-road vehicles did go down to 24,581, but that's still an increase of 910 vehicles, or 4 percent, since his first term, according to the Department of Citywide Administrative Services.

Nonetheless, the administration celebrated its small victories. The city met its goal — ahead of schedule — to remove 1,000 gas-guzzling government vehicles from the road by June, 2021. And it has managed to reduce its total fossil fuel use by 19 percent, despite managing a total fleet — which includes generators, light towers, forklifts, and containers — that is 12-percent larger, according to DCAS.

And its electric fleet has increased from just 618 units in 2013 to 3,135 in 2021 — helping to meet its original 2025 target of 2,000 electric vehicles in 2018, seven years early. The city has since updated that goal to at least double the number of electric vehicles — 4,000 — by 2025, which it’s also on track to hit, according to a DCAS spokesperson.

Just days before leaving office, Mayor de Blasio announced a $420-million investment for creating a fully green municipal fleet, including looking at the possibility of nixing his beloved SUVs altogether.

“We have a lot of vehicles. They have to all become electric," de Blasio said on Dec. 22. "We have sped up our previous goals because of the urgency. Every vehicle will eventually be electric, whether it's a school bus or a public safety vehicle or the cars that officials drive around in. And speaking of those officials, we are requiring those vehicles to be converted to electric in the very near term. And we also want to get away from SUVs once and for all, there are better alternatives available and more and more green alternatives available. That's where we need to go.”

Vehicle electrification is only a part of the problem of cars and other vehicles. Actually reducing the number of cars, trucks, and SUVs — both private and those owned by the city — is the real long-term goal of advocates of livable, safe streets.

“The transition to electrification of the city fleet is really critical, and doing an evaluation of the use of SUVs is necessary and appropriate," said Julie Tighe, president of New York League of Conservation Voters. "People are by far the biggest culprits."

Breaking the car culture, or not

Promoting public transit and getting New Yorkers to part with their dependence on private automobiles starts with having a mayor who leads by example — like by biking, and riding the subways and buses himself. But Mayor de Blasio didn't, except for the odd photo op, and the result is a city filled with dangerous gridlock that costs New Yorkers their time, money, and lives, experts and advocates say.

“Mayor de Blasio should have done more to support public transit," said Kevin Garcia, a transportation planner with the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance. "For example, he opposed congestion pricing for years before he finally came around. It's obvious that traffic is returning to pre-pandemic levels and with that, we expect to see greater emissions in our city. The majority of bus riders come from low-income households and are New Yorkers of color. With bus speeds falling, these are the New Yorkers that are going to pay for increased emissions with their health and bear the brunt of the inconveniences of our crumbling public transit infrastructure."

Instead, the car-loving mayor has said his time is more important than the 8 million people he represents. When challenged by reporters to take the subway, he said he wanted to, but could not because he had "a lot going on."

Even during what were supposed to be so-called “Gridlock Alert” days for the UN General Assembly in September, people continued driving into Manhattan in roughly the same numbers as the week prior, Streetsblog reported at the time — a result of the mayor’s failure to create policies — HOV lane mandates, for example, or road closures — that get people out of cars and into mass transit, advocates said.

It's not clear exactly how many more private cars are on the road now, as the city doesn’t track that data and the New York State Department of Motor Vehicles won’t provide it explicitly. But according to stats and anecdotal evidence — both on the road, and in the form of New York Times exposes — it’s a lot more.

This much is clear: According to the DMV, residents of the five boroughs registered 419,845 new vehicles as of Dec. 1 — up 53,397 from 2020, and 55,156 from 2019, or about 15 percent. Not every new registration is a new car, but the post-pandemic increase in new registrations — i.e. people who've acquired a car, either new or used, and registered it in their name for the first time — certainly means there are tens of thousands more cars on the road, a DMV spokesman said.

And according to a DOT report released earlier this month, the number of household vehicle registrations increased by 8.7 percent between 2010 (before de Blasio took office) and 2020 — before the pandemic car-buying spree. It's unclear how many of the new cars on the road are a result of the city's growing population, which rose by about 400,000 people from 8.4 million in January, 2014, to roughly 8.8 million today, according to city estimates.

Statistics from the MTA further prove that New Yorkers are abandoning public transportation for private cars, either their own, or in the form of app-based taxis, which have also skyrocketed during Blasio's tenure. Bus and subway ridership compared to pre-pandemic days is still hovering around just 50 and 60 percent, while the number of cars driving across the state-owned bridges and tunnels is roughly 90 percent of pre-pandemic "normals," with some days topping 100 percent. For example, on Dec. 14 — a typical Tuesday — a whopping 894,669 cars crossed the bridges and tunnels, 103.3 percent of a comparable pre-pandemic day, according to MTA data.

And in 2013, the year before de Blasio took office, the total number of Vehicles Miles Traveled for all cars and trucks in the city, excluding buses, was 21.042 billion. In 2017, halfway through de Blasio’s tenure, that number rose to 21.3 billion. And in 2019, it rose again to 21.4 billion, according to city data — increases of .4 percent from 2017 to 2019 and 1.8 percent since 2013, according to data provided by the city.

Small jumps, but still indicative of the mayor’s failure to get people out of their cars, especially when that number should be trending the other way, according to transit and carbon emission expert Charles Komanoff.

“It should have been going down,” said Komanoff, who frequently contributes to Streetsblog. "If we had a climate mayor, and a mayor who understood that to help New York City prosper, we would be heightening and building on the city’s asset, which is low-car, high transit. ... And he didn't do that."

The mayor had a small window of opportunity to incentivize people to get out of their private cars and onto public transit, like when fewer people were driving during the height of the pandemic — as much as 93 percent less in Manhattan, according to an NYU study.

Last May, after advocates started sounding the alarm over the likely surge in car ownership and congestion as many New Yorkers were, and still are, avoiding the subways, the mayor finally created a panel to offer insight and suggestions into how to mitigate the influx of traffic as the city reopened.

But as he did with his own expert panel on the BQE, the mayor ignored the panel's robust suggestions — including building out at least 40 miles of emergency bus lanes, 60 miles of busways, and expanding the bike network.

A city with more cars

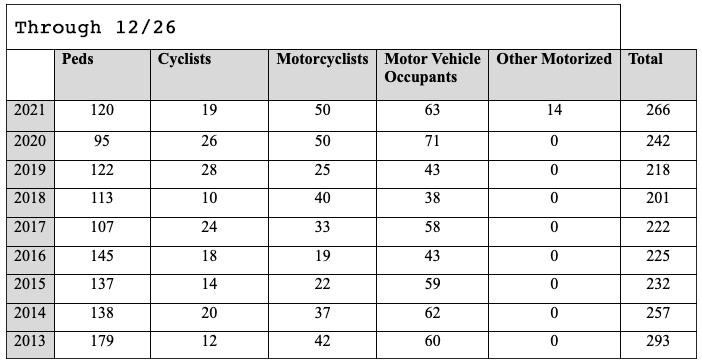

The result of a city with more cars on the road is a city with more crashes and more bloodshed. Through Dec. 26, 266 people have been killed in the five boroughs this year, including 120 pedestrians and 19 cyclists — the highest number since de Blasio took office in 2014, when 257 people were killed through the same date that year.

The mayor did successfully help curb traffic violence for several years throughout his two-terms — though in 2019, 29 cyclists were killed, the highest number since 2000, Gothamist reported. But as more New Yorkers took to cars, the carnage started rising again.

And the other group of people to bear the brunt of the increase in car ownership is bus riders, many of whom are low-income essential workers. Bus speeds are now slower than they were when de Blasio took office. Recent data from the MTA shows buses citywide crawled along at an average of just 8 miles per hour — down from 8.2 mph in January 2015, when the first of such data was published. They hit their peak of six years — 9.2 mph — during the height of the pandemic in April and May 2020, when there were fewer cars on the road and less congestion.

The problem is now in Mayor-elect Adams's hands, according to advocates. Also on the next administration's shoulders is actually implementing the hundreds of miles of new protected bike lanes and bus lanes as outlined in the long-awaited Streets Master Plan, and supporting alternative modes of transportation like electric bicycles.

“For a walkable city with the most extensive public transit in the nation, there are still vastly too many cars, too much unrestricted parking, and too many travel lanes given to private cars," said Danny Pearlstein of Riders Alliance. "Despite some progress on bus lanes, this administration hasn't boosted bus speeds nor moved the needle and decisively cut driving. Now the next administration will need to meet those challenges head on."

Nonetheless, a spokesperson for de Blasio remains defiant that the mayor did more to get people out of their cars and onto public transit — be it by building out busways, bike lanes, and open streets — than of his predecessors, all of which will have a lasting positive impact on the city.

“No mayor has ever done more to make public transit more attractive. This administration built almost half the bus lanes that have ever existed; re-imagined iconic infrastructure like the Brooklyn Bridge to be friendlier to cyclists; and used Open Streets and Open Restaurants to repurpose street space away from private vehicles," said Mitch Schwartz. "He also did what other mayors hadn’t: he leveled with New Yorkers about the scale of the dual climate and congestion challenges, and he told them explicitly to leave their vehicles at home – or never buy them in the first place. That’s an immense rhetorical shift for a mayor of this city. The challenge remains, but this mayor has acted boldly and permanently changed the conversation.”