A study on congestion pricing that the MTA was required to give the federal government predicted that the drop in traffic volume attributed to the toll would be larger than previously believed.

The MTA submitted the study, titled "New York's Central Business District Tolling Program: Program Overview and Traffic and Revenue Study," to the Federal Highway Administration in January 2020. The study was part of the exchange of information between the agencies when the federal government was determining whether the MTA needed to complete a full environmental impact statement or an easier environmental assessment before it could institute its congestion pricing program, a process that was eventually bogged down by political interference from the Trump administration. News coverage at the time referenced the document, but Streetsblog obtained the "traffic and revenue study" via a Freedom of Information Law request.

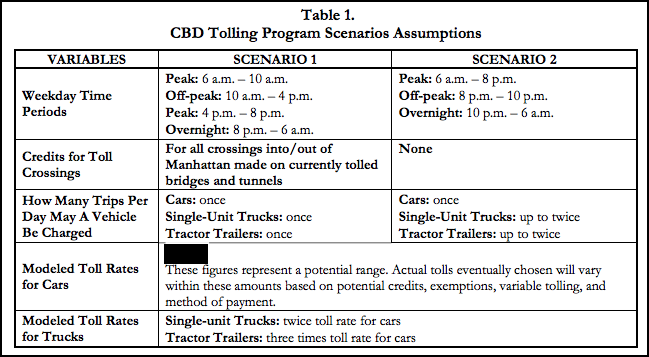

The study, prepared by engineering consultants WSP, explored what would happen in three different scenarios: One in which congestion pricing was not instituted; one in which it was instituted with two shorter rush hour peak tolls and toll credits for Manhattan crossings that are already tolled (Scenario 1 below); and one in which tolls were set with long peak and overnight prices and drivers got no credits for being tolled (Scenario 2).

To determine the traffic impacts under the two scenarios, WSP used 2017 traffic figures as a "conservative estimate of expected revenues." Congestion pricing expert Charles Komanoff said vehicle traffic more or less remained unchanged through the years.

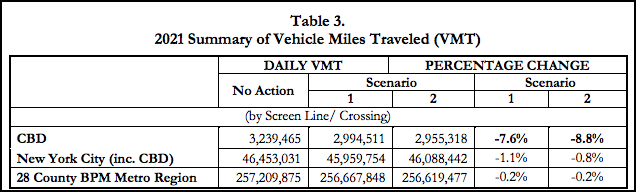

Using that data, WSP found that congestion pricing will significantly cut total vehicle miles traveled inside Manhattan's central living district, and even contribute to a sizable drop in VMT for the whole city. In Scenario 1, VMT within the so-called Central Business District drop by 7.6 percent, and in Scenario 2, the total mileage drops by 8.8 percent.

The percentage drop is smaller for the entire city, but would still result in 364,589 to 493,277 miles not being driven. That's only a drop of roughly 1 percent for the city, but it still "would produce a significant improvement both in traffic congestion and in vehicles emissions," the study authors told the federal government.

Advocates for congestion pricing and better transit said that the study's VMT reductions showed that congestion pricing could reduce driving even more than the Bloomberg-era proposal to toll drivers south of 60th Street in Manhattan, but not on the East River bridges.

"One thing that's clear is that the program the MTA envisions; a Manhattan CBD cordon, $15-billion bonded revenue target, no additional carveouts, whatever toll rate submitted to the federal government, will make a substantial traffic reduction impact," said TransitCenter Director of Communications Ben Fried. "The 2008-era proposal was projected to reduce mileage in the CBD about 6.5 percent. This is projected to be a percentage point or two more."

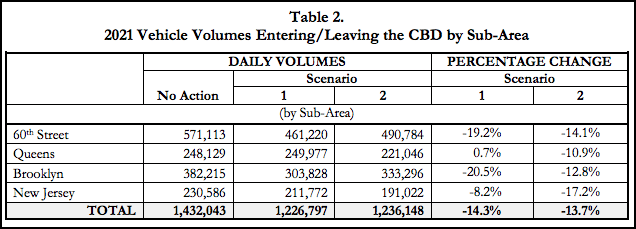

The study also touched on a very high-level view of what would happen to raw traffic volumes in both scenarios and the scenario where congestion pricing was not implemented by now. For vehicles entering the CBD through 60th Street, WSP found that there would be traffic volume reductions somewhere between 14.1 percent and 19.2 percent. It's a figure that lines up with what the MTA has told audiences at its congestion pricing public meetings, where congestion pricing project lead Allison C de Cerreño has said that the MTA's in-house figures show a traffic drop between 15 and 20 percent.

Fried said he understood that the report was put together for a "specific, limited purpose," but did say he would have preferred to see the borough-based vehicle traffic reductions replaced with reductions on the East River Bridges and Hudson River crossings themselves.

"To me it would make more sense to look at each crossing. In a rebate scenario, the Queensboro Bridge will see less traffic while the Queens-Midtown Tunnel will see more. You can generally tell from the numbers here that the areas with the worst traffic burden, the Brooklyn crossings and Midtown, get a bigger reduction from the rebate scenario, but it would be good to see more detail," he said.

The study is limited in that it only deals with the bird's-eye view of traffic by borough, leaving out how exactly neighborhoods on the periphery of the congestion zone might fare. It also does not take into account the way that congestion pricing could affect commercial deliveries into Manhattan. The MTA, for its part, called the study a preliminary analysis and that additional aspects of the traffic impacts are being included in the ongoing environmental assessment, which is taking months and months.

"The specific assessment of neighborhood effects is still in progress," said MTA spokesperson Aaron Donovan. "The Traffic Study was a very early view of some preliminary analysis and provided a high-level view of the potential effects of [congestion pricing]. The environmental assessment will be looking at the impact of the program on freight movements."

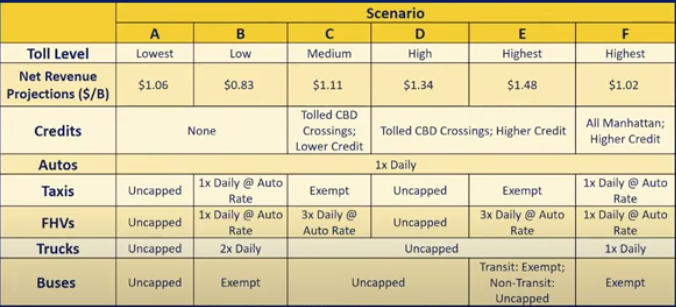

Unfortunately, the MTA redacted the toll range and revenue predictions that WSP shared with the federal government under the claim that money aspect of the study was not a "final agency policy or determination." A recent MTA environmental justice webinar revealed that the agency, which previously said that tolls could range from $9 to $23 for EZ-Pass users, is weighing a number of rebate and revenue scenarios that could net the agency between $830 million and $1.48 billion, depending on the credits and caps on for-hire vehicles and credits. (By law, the tolling is required to raise enough revenue to bond out $15 billion for the 2020-2024 capital plan.)

The report, which relied on modeling used by the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council, undercounted transit trips into the CBD, according to Komanoff. Where the NYMTC model says that 75 percent of CBD trips are made on transit, Komanoff said his Balanced Transportation Analyzer shows that the number is actually 82 percent. The exact count matters because separating through-trips from people's ultimate destinations can help prop up the case that congestion pricing won't hollow out Manhattan's core.

"In a way, so what?" he said. "But I think what they're doing is this fairly common fallacy. Remember, a non-insignificant number of the trips that enter the CBD by car are going through. They're trips that are going to pay the toll, but they're not trips into the Manhattan CBD. I think that's sort of an important distinction. One of the fears about congestion pricing tends to be that fewer people are going to come to the CBD," he said. "One of the reasons that we're not going to lose people coming to the CBD is that a fairly large number of the trips that are going to be priced off the road are trips that go through. Those are not trips that ka-ching the cash registers within Manhattan."