On Thursday, the process to implement America's first-ever congestion pricing system right here in New York City moves another place on the game board when the MTA and friends hold the first of 13 public meetings on the program. The meetings will open the public segment of the 16-month environmental assessment process that the Federal Highway Administration asked the MTA to undergo before getting approval to charge drivers a still-unspecified fee to enter Manhattan south of 60th Street, an area known as the Central Business District. Trying to remember how we got here and where it's all going? We're here to help.

Oh god why is this happening?

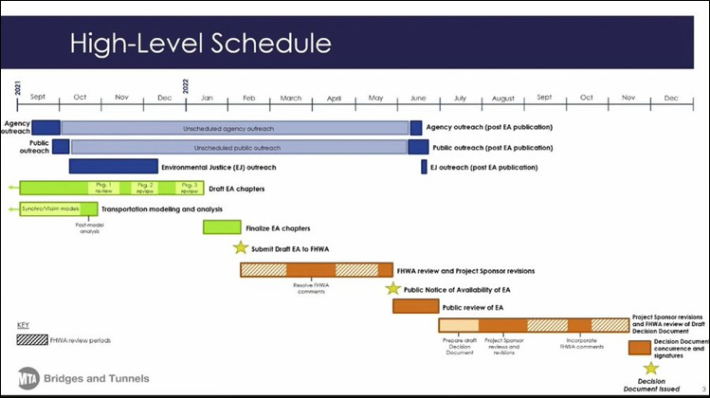

Setting up a toll doesn't always trigger federal involvement. But after New York scribbled congestion pricing into law in 2019, we all learned that Uncle Sam must approve any tolls on federal roads — and pieces of Canal Street, First Avenue and Second Avenue are considered "federal" because they received U.S. greenbacks in the past. The permission (or rejection) will come after an environmental assessment that the MTA is undertaking over the next 16 months. The timeline for it looks like this:

You think 16 months is a long time? The MTA says you're wrong.

MTA Chairman and CEO Janno Lieber presented a compelling counterargument at last week's MTA Board meeting to those (like the mayor) who think it shouldn't take 16 months to do the environmental assessment of something created to reduce pollution and congestion (especially when Detroit doesn't have to do an environmental assessment for the 140,000 new cars New Yorkers bought during the pandemic). Lieber thinks 16 months is nothing.

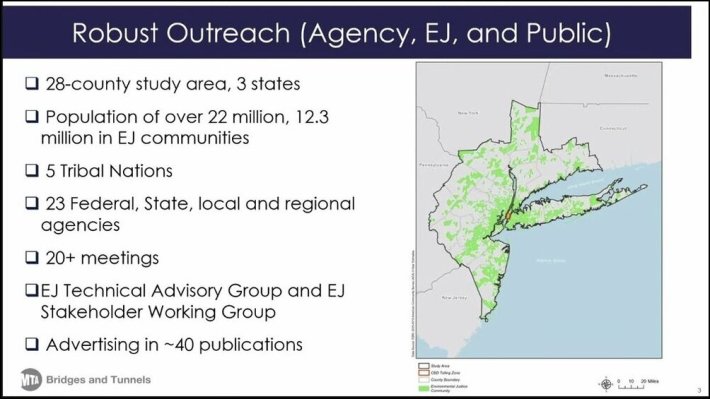

"Sixteen months is incredibly aggressive in schedule," he said. "The Bayonne Bridge, which affected two counties, took 33 months to study under federal environmental law. We're doing 16 months for a 28-county and 22-million-people area so [the schedule] is aggressive. And, equally important, we want to make sure that we don't walk into any legal quagmire."

Lieber's reference to the project to merely raise the deck on the Bayonne Bridge — a project that didn't even involve building an entirely new bridge — reminds us of nightmares past. Here's how the New York Times described what was called the "fast-track" process to rebuild the Bayonne Bridge:

The Port Authority’s “fast-track” approach to a project that will not alter the bridge’s footprint has generated more than 5,000 pages of federally mandated archaeological, traffic, fish habitat, soil, pollution and economic reports that have cost over $2 million. A historical survey of every building within two miles of each end of the bridge alone cost $600,000 — even though none would be affected by the project.

After four years of work, the environmental assessment ... took into consideration comments from 307 organizations or individuals. The report invoked 207 acronyms, including M.B.T.A. (Migratory Bird Treaty Act) and N.L.R. (No Longer Regulated). Fifty-five federal, state and local agencies were consulted and 47 permits were required from 19 of them. Fifty Indian tribes from as far away as Oklahoma were invited to weigh in on whether the project impinged on native ground that touches the steel-arch bridge’s foundation.

So, as with anything in life, it's always worth remembering that it can be much much worse. Lieber did go on to say that the 16-month schedule isn't carved into stone tablets and that "nobody is saying that if there are opportunities to shrink it further that those won't be acted on." As it happens, Riders Alliance is having a rally on Sunday specifically to pressure Gov. Hochul into finding those opportunities.

We don't have years to fix our subway, clean our air, and put and end to carmageddon. We have to do it today.

— 🚇 Riders Alliance (@RidersAlliance) September 14, 2021

Rally with us on September 26 to demand congestion pricing now!

🔥https://t.co/9S1q44FQlQ🔥 pic.twitter.com/7XKa3OeBzq

So what is actually being assessed over the next year and half?

The environmental assessment will study whether the impacts of instituting a toll to drive into Manhattan south of 60th Street could be so significant that they warrant even further study by the government in the form of an environmental impact statement. The assessment must cover areas such air quality, noise and economic effects — plus whether specific communities such as Native Americans or populations that have traditionally been adversely affected by environmental injustice feel an adverse impact because of a project.

The latter two are populations that are included in all environmental reviews, as the government's breakdown of the National Environmental Policy Act lays out: any federal study requires "meaningful coordination with Tribal entities, and analysis of a proposed action's potential affect on Tribal lands, resources, or areas of historic significance is an important part of Federal agency decision making." The five tribes that are included in the study area are the federally recognized Shinnecock Nation on Long Island, the New York State-recognized Unkechaug Nation of Poospatuck Indians in Mastic (also on Long Island), the New Jersey-recognized Ramapough Lunaape Nation in Mahwah and the Connecticut-recognized Golden Hill Paugussett Nation in Trumbull and Schaghticoke Tribal Nation in Derby.

The specific assessment area, which was decided on after months of negotiations among the federal government and the MTA, New York State DOT and New York City DOT, covers the five boroughs, Long Island, the suburbs north of the city up to the Massachusetts border (!), half of New Jersey (west to the Pennsylvania border!) and part of western Connecticut. The area of "impact" is so vast on the map below that you might not even be able to see the congestion zone (red blurry part near the center):

Jesus Christ.

Yeah, people have not reacted very well to this map, accusing the federal government of allowing New Jersey and Dutchess County veto power over how the city gets control of its streets. But that's the map. Why? Per Lieber, it's because congestion pricing could cause cascading regional effects, not just direct impacts to the five boroughs or lower Manhattan.

"The traffic implications, obviously go down through the system. We all know that traffic isn't just a place where you're stopping traffic that it, it cascades through the whole traffic system," Lieber said last Wednesday. "That and the other impacts [NEPA] requires us to study for whatever reason have over time been defined to include that bigger area because of the traffic implications in the air quality and demographics."

Ultimately, the question the government is weighing is not whether congestion pricing has no impact, but rather whether it causes such a significant direct or indirect impact to the region that further study is needed. For instance, when the FHWA asked the Texas Department of Transportation to do an environmental assessment on a proposal to add toll lanes to a highway in Austin, the state weighed impacts such as economic, traffic diversion and travel time to environmental justice communities. That EA reached the conclusion that "environmental justice populations would experience both the adverse and beneficial effects of the SH 71 Express Project; the overall affect is not anticipated to be disproportionately high and adverse."

How do they assess it though?

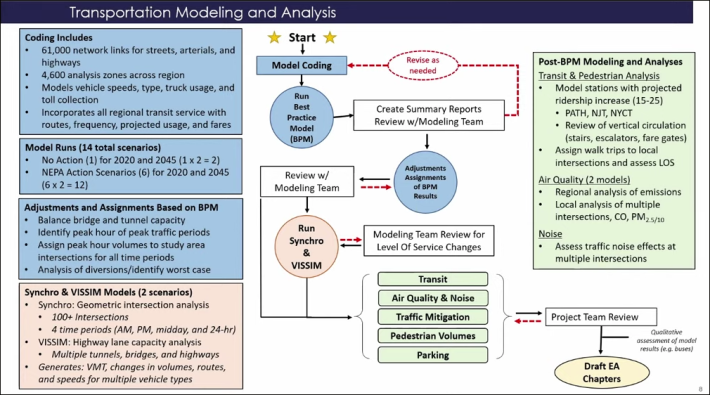

There are a lot of complicated studies being done on the question, a lot of ins, a lot of outs, a lot of what have yous. One piece of the assessment is through traffic modeling. Here's a chart to explain the modeling that the MTA revealed last week, it looks like a Star Wars Expanded Universe continuity tracker.

As you can see, there's a lot going on. The incredibly large study area means that there are tens of thousands of streets, over a hundred key intersections and a handful of public transit companies to study. According to Allison de Cerreño, the MTA's deputy chief operating officer and congestion pricing lead official, the transit authority is looking at two universes of possibilities. One possibility is that congestion pricing never gets instituted and the other is if it does. And within that latter "action alternative," there are multiple possible outcomes to explore.

"For the action alternative, we're going to be running six different scenarios to ensure that we understand the full range of potential environmental effects resulting from different toll rates," she explained on Wednesday. "The 'no action,' and each of the action scenarios, are actually run in two different time periods for a total of 14 scenario runs. Each of those runs needs to be assessed, reviewed, refined. Once this initial model is completed and reviewed, the results then feed two different traffic models. These traffic models will explore the potential effects over 100 different intersections, as well as effects on multiple tunnels, bridges and highways."

The intersections that will initially be studied are those that show traffic increases in the MTA's initial traffic modeling, so that the agency can determine what kind of mitigations can be proposed at the areas.

Wait, does that chart say they're studying how much room there is on the subway stairs?

Well, consider it logically. If fewer people drive into the city as a result of the congestion toll, those people will have to get around a different way, and one of those ways would be the subway. Back in 2018 when the subway was pulling in a record numbers of riders, transportation analyst Charles Komanoff studied the question of whether the subway would be overwhelmed by congestion pricing. The good news is that his analysis found that since the subway system already carries five times more people than the untolled entrances to Manhattan's central business district, the maximum amount of mode shift that could even happen was a 20-percent shift to the subway. But since congestion pricing won't take every car off the road, and rush hour car trips into lower Manhattan account for a small share of total car trips to the area, Komanoff's model found just a 1-percent bump in subway ridership from the halcyon days of high subway use.

He argued last week that the MTA's focus on subway staircases shows how ridiculous this whole process is:

I'm glad @GershKuntzman drew my attention to circled part of @MTA's #congestionpricing analysis plan. Also mad. Why analyze 1% gain in peak-hr subway traffic? (Yep, that's "overnight" gain, before better-subways "carrot" kicks in yrs from now.) More here: https://t.co/hwMbKberdy pic.twitter.com/T1ZafyVDzR

— Charles Komanoff (@Komanoff) September 15, 2021

Yeah that all makes sense. Sounds good.

Oh, just one more thing.

What's that?

There are public meetings on congestion pricing.

Come on.

You come on, didn't you read the lede? Starting on Sept. 23, the MTA and company will have two weeks of meetings during which the public can learn about congestion pricing and why its being implemented, or merely just weigh in. Each meeting will be focused on a different geographic area that the federal government decided could be impacted by congestion pricing (see that crazy map above). While each meeting and presentation is focused on a specific area, you don't need to live in that area in order to watch the meeting or add your comment. (The schedule of all the meetings is at the bottom of this post.)

How will these meetings work?

According to the MTA, the meetings will be similar to public meetings on fare hikes. That means there will be a presentation on the basics of congestion pricing and the environmental assessment process that it's going through. After that, members of the public will get to make comments on both congestion pricing and the environmental assessment process.

Who's listening to us at these meetings?

De Cerreño will be running point on the presentation side, but also on hand will be representatives from the Federal Highway Administration, the New York State DOT and the New York City DOT.

What will happen to our comments?

They go right into the shredder. Haha, just kidding. Every comment received at public meetings will be "aggregated and indexed so they can be addressed as part of the EA process," according to Ken Lovett, the Senior Advisor to the MTA Chairman and CEO. Don't believe it? Well, if you really want to have a good time, check out how the Texas DOT put all of the public comments for its toll proposal into an appendix on the environmental assessment [pg. 319]. Go ahead and read the comments, the knowledge may save your life one day. (That project only had a single public hearing.)

If you can't make it to a meeting, you can also comment through the website, over the phone (call 646-252-7440), via email or even by good old fashioned letter writing (to CBD Tolling Program, 2 Broadway, 23rd Floor, New York, NY 10004). There's also going to be a chance for the public to comment on the draft environmental assessment when that comes out, so you have a lot of opportunities to weigh in on this thing.

Are congestion pricing opponents weighing in on this?

Yeah. Take, for instance, longtime congestion pricing foe Assembly Member David Weprin. Weprin told Streetsblog that he believed the only reason the tolling program made it through the budget process in 2019 was because then-pre-disgrace-Gov. Cuomo twisted legislators' arms and added the law to the state budget. Weprin also said that not enough study has been done on non-commuter driving patterns into Manhattan, the kind of people he said lived in his district. He also didn't back off his proposal that the MTA wait until "two years after the pandemic" to institute congestion pricing, even though the agency may not start collecting money from the program until 2024 under the current timeline. Why? The agency doesn't need the money, Weprin claimed.

"The MTA just got $20 billion over the last year in extra money, because of the pandemic, you know, let's let them spend that money," Weprin said. "And where's that money going? I just don't trust the MTA."

That money, which was not extra money as much as it was a lifeline for an agency running out of money, was specifically earmarked for the MTA's operating budget after ridership dropped by as much as 90 percent during the early days of the pandemic.

Do I have to weigh in on this thing?

A lot of people are exhausted and would rather do something like sit on the couch with a nice cup of poison than beg a federal administrator for cleaner air, safer streets and reliable public transit. But right now congestion pricing is caught in the dreaded "Valley of Death," the period between legislative order and actual program implementation where the specter of an unknown toll can be used to whip up opposition to congestion pricing because the only thing people can see is the toll and not the program's benefits. So if you're reading this, yes, it's in your interest to submit an online comment or even attend one of the meetings in order to ensure officials don't come away with the impression that there's such an adverse impact to the study area population that this whole thing merits even more study.

And don't forget that a lot is riding on all of this. While the MTA says that 700,000 vehicles drove into the CBD every day before COVID-19, that represented just one-quarter of the people who entered the CBD. Almost three quarters of those travelers got in by subway, bus, commuter rail or ferry. Congestion pricing is legally mandated to raise $1 billion in revenue each year, which will initially be used to back $15 billion in bonds for the 202-2024 MTA capital plan. In order to build a better transit system for our current and future population, the MTA has to modernize its signals, its trains, its buses other critical infrastructure.

Will these meetings also just be a lot people explaining why they personally should be exempt from the congestion pricing toll because, you know, cars?

There's probably going to be some of that, sure, but it's also nothing that the MTA isn't expecting, and is figuring into its multiverse of traffic models.

"Those six scenarios where we build the central business district tolling program each have a combination of potential exemptions credits, discounts, or none of the above in order to give us a full range and understand the effects of the decisions and what happens on the congestion and the revenue and the vehicles coming into the central business district," de Cerreño told the MTA Board.

It's as good a situation as any to remind everyone that because congestion pricing is legally required to raise $1 billion, every exemption to someone driving over the Williamsburg Bridge to grab a slice at Roma Pizza, as one does, will mean that everyone who's not exempt has to pay a higher toll.

There have been a few attempts to get exemptions so far including: Weprin asking for all New York City residents to be exempted from the charge, Police Benevolent Association President Pat Lynch asking all police to be exempt, Brooklyn Borough President and presumed mayor Eric Adams asking for exemptions using an ill-defined idea of who's driving into Manhattan as a luxury, and, of course, Rep. Josh Gottheimer, Democrat of New Jersey, who is demanding an exemption for any New Jersey driver, bound for the central business district, who comes over the George Washington Bridge.

Shouldn't drivers just be happy that there isn't a popular revolt where the fed-up population of New York City begins pushing cars into the East River?

You could try that. You could also use your comment time to point out that there's something in congestion pricing for drivers, too. As the Fix NYC Panel tasked with creating a congestion pricing plan for the city pointed out in 2017, when Singapore, London and Stockholm instituted congestion pricing it resulted in increased travel speeds in the central business districts of each city. Maybe some people don't want the tradeoff of paying some money to make their car trips less of a drag on their total lifespans, but there are also people who want to ban cars from Manhattan entirely. So really this whole thing is a compromise when you think about it.

Seems pretty unfair that the federal government doesn't ask non-drivers to weigh in when 140,000 new cars are registered in New York City ... like that's normal or something.

Well, sorry if someone told you life was fair or worth living. Unfortunately, NEPA is a law that specifically "requires review of the effects of all Federal, federally assisted, and federally licensed actions," and there's no federal law limiting the amount of cars built or existing in the United States. So they just keep churning them out, year after year...

Here is a full list of the upcoming congestion pricing meetings and the zones from which public comment is sought. According to the MTA, speakers will have up to two minutes to comment. If you just want to watch, click here for the livestream. Each meeting has its own sign-up link, which is in blue below:

Thursday, Sept. 23, 10 a.m.: The Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island

Thursday, Sept. 23, 6 p.m.: Manhattan Central Business District (60th Street and below)

Friday, Sept. 24, 10 a.m.: New Jersey

Wednesday, Sept. 29, 10 a.m.: Northern New York City Suburbs

Wednesday, Sept. 29, 6 p.m.: Long Island

Thursday, Sept. 30, 6 p.m.: The Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island

Friday, Oct. 1, 1 p.m.: Connecticut

Monday, Oct. 4, 6 p.m.: New Jersey

Tuesday, Oct. 5, 6 p.m.: Northern New York City Suburbs

Wednesday, Oct. 6, 6 p.m.: Manhattan Outside the Central Business District (61st Street and above)

In addition, three virtual meetings will be held, focused on environmental justice communities located respectively in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, though anyone may register to attend any or all of these:

Thursday, Oct. 7, 6 p.m.: New York

Tuesday, Oct. 12, 6 p.m.: New Jersey

Wednesday, Oct. 13, 6 p.m.: Connecticut