New verse, same as the rest?

Brooklyn Assembly Member Peter Abbate has sued to stop the city from fixing a pair of chaotic Sunset Park avenues — a safety-stopping lawsuit that borrows a well-worn argument that the Department of Transportation doesn't have the authority to make street changes. It follows similar failed suits to stop the Prospect Park West bike lane, the Morris Park Avenue road diet, the Central Park West bike lane and the Flushing Busway.

This newest suit argues that DOT is moving ahead with the safety improvements without properly notifying Community Boards 7, 10 and 12 at least 90 days before construction is supposed to start, a violation of a city law regarding installing or removing a bike lane. That law, passed in 2011, specifically required the DOT to "notify each affected council member and community board via electronic mail of the proposed plans for the bicycle lane within the affected community district and shall offer to make a presentation at a public hearing held by such affected community board."

Abbate's suit demands that a judge block the construction until a full hearing can be held, even though the suit also admits that the DOT has informed community board representatives about the project. In addition, the temporary restraining order sought by Abbate, who represents Dyker Heights, Bath Beach, Bensonhurst and Borough Park, would stop construction on a project that has not started and has no publicly announced start date.

In the suit, CB10 District Manager Josephine Beckmann charges that a DOT representative told her that the agency was going to start making the street changes in August, before any meeting with the community boards was held, but the agency has never publicly committed to a specific month when construction would start. The DOT did not respond to a request for comment, but Beckmann's charge isn't supported by anything but an affidavit in which she's identified as the district manager of both Community Board 10 (of which she is) and Community Board 7 (of which she is not).

But even if construction was supposed to start in August, the DOT has given notice of its intentions multiple times. The agency told CB10 about the prospect of street changes in a November, 2020 presentation [PDF] about making the two avenues safer.

The DOT followed that up with its first Community Advisory Board meeting in May 2021, to which the district managers of all three affected community boards were invited, an outreach effort that, oddly, the plaintiffs entered into evidence as proof that there was no chance for the boards to learn about the developing street safety project.

The suit charges that Community Advisory Boards — individual panels of local stakeholders that the DOT started creating for various projects in summer, 2020 — are a nefarious end-run around the usual community board process. But the fact remains: no DOT project since the advent of Community Advisory Boards has gone from said boards to implementation without the legally mandated community board presentations. Asked about the nature of CABs in January, DOT spokesperson Brian Zumhagen specifically told Streetsblog that they weren't a substitute for the regular community board outreach process.

"DOT continues to post all presentations on our website, and we will still present projects at community boards, in keeping with our regular procedure and process," he said.

Additionally, the DOT's last town hall meeting on the Sunset Park proposal in June still promised that the DOT would still meet with all three affected community boards before the start of construction, which, again, was never put on any calendar. That tri-community board meeting has been part of the project's timeline in every presentation, even as the outreach has dragged along without an end date.

Bizarrely, the suit suggests that a bike lane is being removed on Seventh Avenue, a reading of the project that can only happen if someone considers the existing sharrows on Seventh Avenue to be a "bike lane." The suit also contends that 10 million people live in New York City and that the DOT's Street Ambassadors (agency employees who go out into communities to talk to residents in an attempt to get feedback on proposed street changes) are "a paid posse of youngsters, potentially skewing personal interviews to impress their superiors."

To be sure, the agency has done itself no favors on the transparency front, with a spokesperson not even being able to tell Streetsblog the schedule was for upcoming public outreach, let alone construction.

The DOT proposal would make a series of changes to the commercial heart of Chinatown in Sunset Park, chief among them changing Seventh and Eighth avenues from two-way streets to one-way streets; Seventh Avenue would become southbound only and Eighth would handle northbound traffic. Each strip would also get a protected bike lane, and the west side of heavily commercial and pedestrian-filled Eighth Avenue between 50th and 61st street would get an eight-foot wide sidewalk extension. The DOT says (and Streetsblog has confirmed) that pedestrian volumes on that southern stretch of Eighth Avenue surpassed 5,000 pedestrians an hour, and there is very little room for people to shop, walk and browse.

Abbate's lawsuit doesn't attempt to dispute the facts that the DOT has presented about the block, characterizing the stretch as a "densely populated, traffic and pedestrian congested, combined business and residential community" before going on to suggest that the DOT's solution will be "will be a congested and dangerous transportation nightmare for cars, trucks, buses, cyclists and pedestrians alike."

But the suit seems to ignore that the streets already are congested and dangerous transportation nightmares for every road user, which is why the agency proposed the one-way conversion.

There were 17 severe injuries to pedestrians and 15 severe injuries to motorists on Eighth Avenue between 2014 and 2018 according to data from the DOT, which only focuses on the most severe crashes.

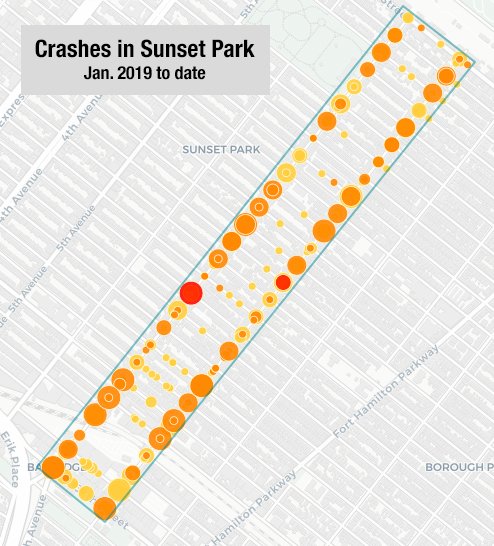

The city's own data visualized by CrashMapper shows that 30 cyclists, 72 pedestrians and 61 motorists have been injured (and two pedestrian killed) in 732 crashes since January, 2019 in the zone being considered for the redesign.

And Transportation Alternatives pointed out that there have been three hit-and-run crashes in 24 hours this week. The group's spokesman said the increase in road deaths in the city this year put lawsuits like Abbate's, as well as a Manhattan community board's fight against a transit and bike lane project on Fifth Avenue, on the wrong side of history.

[It's] quite the split screen to read about these gruesome hit-and-runs while also reading about campaigns to stall bike lane projects in Sunset Park and on Fifth Avenue," Cory Epstein said.

Lawsuits seeking to argue that the city does not have the power to make changes to the street — also known as Article 78 suits after the section of state law that covers governmental power — frequently hinge on the city's alleged failure to do extensive research, environmental modeling or community outreach before implementing street safety or transit improvements. But judges have been increasingly hostile to such arguments, and have ruled in favor of the city consistently.

In 2019, a judge publicly dressed down a lawyer for a group of plaintiffs seeking to block a dedicated bus lane on Fresh Pond Road. In that case, attorney Arthur Schwartz argued that the city did not do sufficient study of the potential environmental impacts of a dedicated bus lane. The judge in that case, Justice Joseph Esposito, told Schwartz that he had "a very parochial, very narrow view" on the city's efforts to make streets safe for all users.

I’m a car driver. I don’t like change either. I don’t like the changes one bit," he said. "But it’s not about me. It’s not about a narrow group of people who use the roads anymore. ... Being a car driver myself, if it was up to me, I’d grant your petition, Mr. Schwartz, but I cannot. [The city is not acting] arbitrary and capricious. It’s rational. It makes perfect sense. This proceeding is dismissed.”