The process that the Department of Transportation uses to make city roadways safer and more hospitable to human beings was revealed — for about the thousandth time this year — to be a broken system of begging car owners to give up their entitlement to virtually every inch of public space and reluctantly agree to help save the planet and their neighbors.

DOT officials ventured to Queens Community Board 3's Traffic and Transportation Committee on Wednesday night to present an update on what the agency considers "the gold standard" of open streets in the mayor's COVID-era program to create more recreation and socially distant gathering places: 34th Avenue in the coronavirus-stricken communities of Jackson Heights and Corona.

But the board members were having none of it. Before the DOT got to say a single word, Committee Co-Chairman Steve Kulhanek launched into a broadside designed to establish the parameters for the discussion:

"It's important for people to understand that the open street came into fruition because of the horrible COVID situation," he said. "The city was looking to do what it could to help people get outside safely. And ... they kinda just implemented it. It was not run through the typical channels of review. The mayor and DOT just kinda did it. We found out only by news reports. We had no involvement in the planning of the play street."

The comment suggests that board members — who are supposed to live in the neighborhoods they represent — did not manage to get out of their cars to experience the open street, which has operated 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. between 69th Street and Junction Boulevard since May.

"What we saw was something wonderful," said John O'Neill, a DOT official, after Kulhanek's monologue.

Agency colleague Stephanie Shaw called 34th Avenue the "gold standard" and added that the roadway was an "incredible success — and we want to build on that success."

Defying her audience, Shaw laid out a range of possibilities for DOT's "phased approach" to keeping the roadway open to walkers and cyclists. The agency said it hopes to start with "light touch interventions" this fall that could lead to "permanent treatments."

"We are looking at 34th Avenue not going back to the way it was pre-COVID," Shaw said.

And then ... the stall.

Multiple board members confronted the agency about the alleged difficulties drivers are having, a form of misinformation, given that drivers can access any part of the open street (as long as they maintain 5 miles per hour). Others complained about the loss of parking spaces, though none has been eliminated. One person complained that people are "hanging out" late into the night after the roadway reopens to cars at 8 p.m., another piece of misinformation (residents of New York tend to "hang out" after 8 p.m. in many locations, open street or not).

And there was the universal complaint from the board: We weren't told this was going to happen.

"We only heard about it in the media," said one board member. (As a point of fact, the mayor's office put out press releases repeatedly since the open street program began in May, updating the mileage in the 70-mile program several times a month. And as another point of fact: The open street exists right there in the middle of Community Board 3; if the board members wanted to get more information, all they had to do was walk out the door. Transportation Alternatives and the 34th Avenue Open Streets Coalition have been petitioning for months, too.)

Knowing their audience, both Shaw and O'Neill promised more community engagement going forward.

Which means more delays.

As described by Shaw and O'Neill, Jackson Heights and Corona residents, whose neighborhoods have among the least amount of public space in the city, will now have to wait as the DOT returns to the community board over many months — likely through the entirety of the remaining days of the de Blasio administration — to engage in dialogue, take surveys and consult stakeholders.

"Once we've had those preliminary conversations, we'll come back with more specific outreach," Shaw said.

"Tonight is the first of a long series of conversations," added O'Neill.

It is clear that coming back to this particular community board is a fool's errand. Rather than treating the city's best open street as a gift that they were lucky to have, the board members who spoke on Wednesday were almost universally opposed to even discussing the permanent open street, which both Council Member Danny Dromm and State Senator Jessica Ramos (who were not allowed to speak at the meeting) have demanded be made permanent.

Car owners — who are the minority of Jackson Heights and Corona residents — complained that residents treat them with hostility, but one board member, Megan Rockwell, pointed out that the only hostility she's seen on 34th Avenue comes from "non-compliant people who drive at full speed. That's hostility."

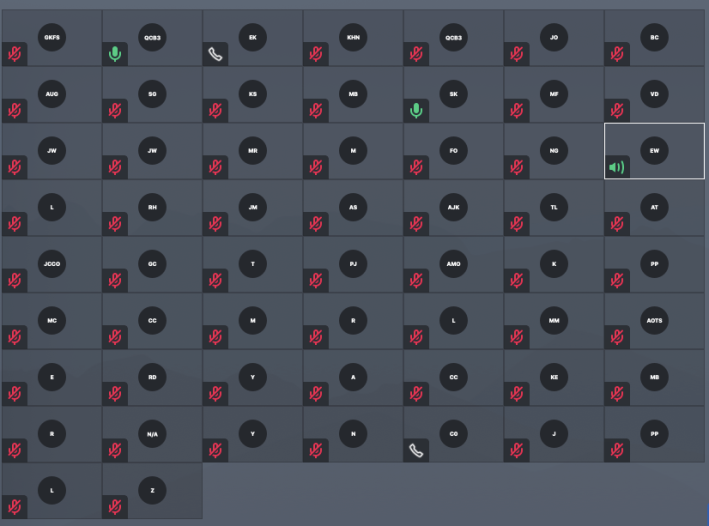

It should be noted that residents of the neighborhood filled the meeting's chat room with pro-open street comments (though it was unclear if the board members were paying attention to it; the board's understanding of technology appeared limited — board members' faces and names were frequently not visible and it was often unclear who was talking. Your government in action.) At least one car owner demanded a "compromise," failing to realize that the open street — with movable gates to allow for local car traffic and parking — is the comprise. If street safety advocates had their way, the roadway would be dug up and planted with trees to create a linear park for residents to enjoy forever.

The meeting was just the latest in a seemingly endless series of community board meetings where DOT officials show up to promote something that would benefit a vast majority of community members — and, indeed, make a roadway safer for all users — only to have members of the board demonstrate concern only for their own parochial, four-wheeled interest. (It was also funny to hear board members say they didn't know anything about the open street, yet engage in an incredibly detailed subsequent discussion about how car traffic flows in the neighborhood — one that showed that the board members understand every burp, spit, traffic light and pothole in their neighborhoods when they want to.)

Last week, a Manhattan community board shot down a loading zone for a supermarket because it would remove some car parking. And also last week, a Queens community board district manager fought to move some Citi Bike docks because she was afraid of losing parking spaces. It's the kind of thing that delays the process as DOT spends unnecessary resources trying to appease the forces of yesterday rather than building a better tomorrow. Activists have to fight the same battle over and over and over again, wasting resources that could be better spent on progress, not stagnation.

In this case, the board will likely delay any implementation of even Shaw's "light" interventions, but, of course, there is another alternative: the mayor can make good on his recent chat with Ramos and just make the improvements that he reportedly wants to make.

In any event, it is unclear what the next step will be ... except a lot of talk.