Self-styled progressives in Manhattan are calling in the cops to crack down on e-bike riders, again, despite a law that legalizes the rides and their own professed opposition to police brutality.

The Hudson River Park Trust Advisory Council wants e-bike riders to be ticketed on the Hudson River Greenway — where electric bicycles were made illegal under a state law legalizing them everywhere else — and New York State Department of Transportation Regional Director Craig Ruyle told the group that his agency could do more about "enforcement" (read: police) against e-bike riders.

"We can work with HRPT to try to get NYPD to do some enforcement, but by ourselves we don't have any enforcement capability. But we're more than willing to work with NYPD to see what we can do," Ruyle told the council after one member kicked off complaints about the presence of e-bike riders on the greenway.

The park's Advisory Council is made up in part of members of Manhattan Community Boards 1, 2 and 4. Earlier this year, CB2 established an Equity Working Group "to empower and celebrate the contributions of our traditionally marginalized, underrepresented and underresourced community members," while CB1 passed a resolution regarding "Unequivocal Support For Black Lives and The Right to Protest Police Brutality." Yet these resolutions did not stop the HRPT from asking the state DOT to involve the same NYPD that's brutalized cyclists of color and imposed hardships on working cyclists in a misguided public safety campaign.

"Is there anything that you can do to actually enforce the rules of the greenway?" asked HRPT Vice-Chair Daniel Miller, "To get the motor scooters that are going 30, 40 miles an hour on the Greenway and actually enforce it so that they're punished? And put signage up that says this is not a racetrack...rather than having to navigate while a 40 mile an hour cyclist is passing you?"

Miller, whose signature was on the CB2 letter purporting to "acknowledge the generational and institutional racism that our Black and brown brothers, sisters and non-binary community members have suffered," either conflated the use of actual mopeds with the use of e-bikes, or stuck by the old canard that the bikes move much faster than they actually do.

Class 3 e-bikes, the throttle-powered type preferred by delivery riders, max out at 28 miles per hour, but state law restricts the bikes to 25 miles per hour. Ruyle did not specify whether the e-bike ban would be a blanket ban on every class of e-bike, or if some types would be exempted from the ban. Under state law, e-bikes are classified as Class 1 (pedal-assist bikes that max out at 20 miles per hour), Class 2 (throttle-powered e-bikes that max out at 20 miles per hour) and Class 3 (throttle-powered e-bikes that max out at 25 miles per hour and are only legal in New York City) e-bikes. All are illegal on the greenway — even pedal-assist Citi Bike bikes.

"We can work with HRPT to put some signage up indicating that so it's known that it's illegal to be on the bikeway with electric bikes and scooters," said Ruyle.

But Transportation Alternatives Deputy Director Marco Conner DiAquoi cautioned against a ban on just Class 3 bikes, which he said was not backed up by any data and put delivery riders at risk.

"In the absence of actual data that shows this is a safety issue, there should not be a ban on Class 3 e-bikes, because we have over 30,000 delivery riders in New York City, and the greenway is a place for them to ride safely," said Conner.

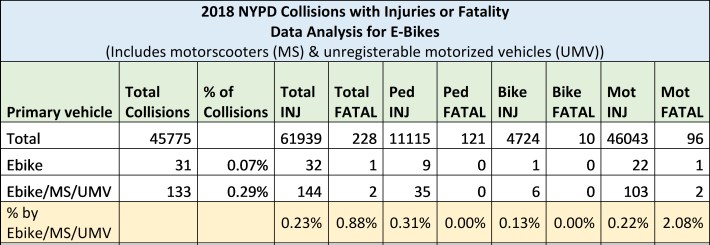

The data on e-bikes shows them to be relatively safe. For instance, the NYPD's 2018 traffic collision data showed that e-bike riders were involved in just 31 out of 45,775 motor vehicle collisions and only injured nine pedestrians all year.

The conversation on enforcement was an unfortunate outgrowth of the stated purpose for why the state DOT showed up at the advisory council meeting. Ruyle was there to discuss the proposal that West Side community boards had made to take a lane of traffic from West Street and turn it into a southbound bike lane, which they asked for because of overcrowded conditions on the greenway's bike and pedestrian path. But Ruyle told the council that the state DOT was "not comfortable" with the idea of removing a lane of traffic, shortly before both sides determined they were comfortable asking the NYPD to get involved on the greenway.

Ruyle's promise to work on signage and police staffing on the greenway puts more urgency behind advocates' previous calls for the City Council to use its home rule powers to open the greenway bike path for e-bike riders, which they said was a necessary fix back in April.

The Council didn't act on the issue when it passed its own package of e-bike and e-scooter legislation, a set of bills (since signed by Mayor de Blasio) that mirrored the state law creating Class 1, 2 and 3 e-bikes in New York, but local legislators said that the state DOT announcement would spur them into action.

"Instead of building out the appropriate resources in city and state infrastructure, they're banning things and stopping people from using these bikes like the law intended," said City Council Member Antonio Reynoso. "I think it's bad planning, and the onus should be on the city to do something, not on the state to over-regulate and ban folks from using the greenway. I'll be working on it pretty quickly with a couple of my colleagues to figure out something we can do immediately."

The state bill legalizing pedal-assist and throttle e-bikes prohibited riders from using them on any greenways across the state, but the bill does gives broad home rule powers to municipalities to set their own rules. Conner previously argued that provision of the bill meant that the city can clear the way for e-bike riders with the powers it has under New York State Vehicle and Traffic Law 1642, which says cities with a population of over one million people are allowed to "regulate traffic on or pedestrian use of any highway (which, for the purposes of this section, shall include any private road open to public motor vehicle traffic)."

The greenway itself is subject to a confusing mishmash of bureaucracies. It's owned by the state DOT, the city DOT is responsible for policing and traffic signal timing on the path and the Hudson River Park Trust is responsible for path maintenance. But according to Conner, the City Council has the authority to set a speed limit on the greenway, and as such suggested that a speed limit is a better option than a total e-bike ban.

"We have cars on the road that can reach speeds of 100 miles per hour, governed by speed limits of 25 miles per hour. A much easier way of doing this would be to put up signs about a speed limit of say, 20 miles per hour. You want to be careful about how it's enforced, but just as with road speed limits, even though there's a minority of drivers who don't follow the law, that's no reason to do away with it," he said.

City Council Member Ydanis Rodriguez, who chairs the Transportation Committee, also said that he preferred a speed limit on the greenway instead.

"I am ready to work with my colleagues and advocates on legislation that will prioritize the safety of riders and pedestrians, while also protecting the delivery workers from unnecessary seizures," said Rodriguez. "However, I do believe that since the greenways consist of shared spaces between pedestrians and cyclists, we must regulate the speed limit at which e-bikes should be allowed to go while traveling on them."

The latest effort by supposed liberals to call in the cops against people who more likely to be harmed by the police than the mostly White residents of the neighborhood. In June, a Community Board 7 committee voted 7-1 to ask the NYPD to step up its enforcement of dog-off-leash tickets. Earlier that month, the same "progressive" community board asked for more policing of bike traffic in Central Park.