We could just cut-and-paste it from about 50 previous stories, but here goes: Manhattan's central business district will become gridlocked with cars — no matter how strongly the economy roars back — unless city officials immediately "prioritize road and street space for pedestrians, cyclists, buses and high-occupancy vehicles," a new report says.

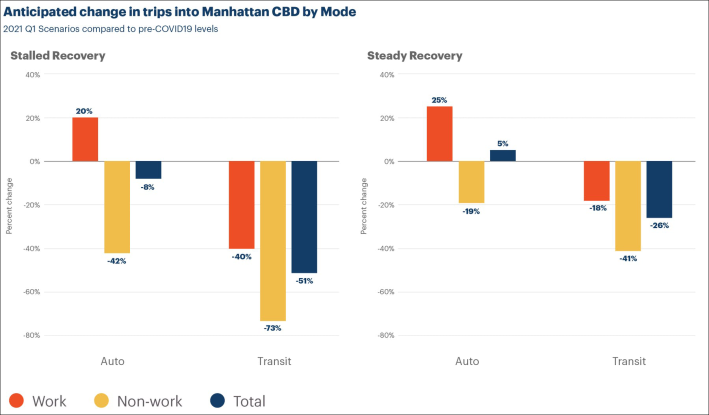

The Regional Plan Association studied two scenarios for the rebounding economy: A "stalled" recovery where commuters to Manhattan below 59th Street return to only 50 percent of pre-pandemic levels, and a "steady" recovery with two-thirds of workers returning. How many people is that? It's a half-million to one million more people traveling into Manhattan than when the economy was locked down in April.

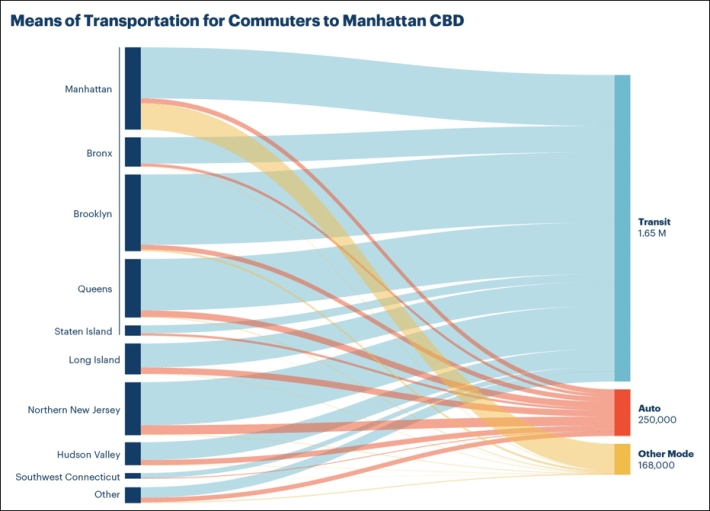

In either scenario, transit ridership fails to fully recover — and largely well-to-do commuters, who have access to cars, take advantage of ample roadways. Of the 250,000 commuters who typical use cars to get into Manhattan, a large portion is from Long Island, northern New Jersey and upstate New York (see chart).

"The roads will fill up, while transit ridership will remain well below normal," authors Ellis Calvin and Christopher Jones, both of the RPA, wrote [full report].

The report offers multiple recommendations, which will also read as common sense to urbanists, but are mostly rejected by (or not under the jurisdiction of) the de Blasio administration:

- Implement congestion pricing to reduce auto traffic and provide funds to the MTA. (This is currently awaiting — and awaiting and awaiting — federal approval.)

- Reform placard abuse, which congests New York and "endangers other New Yorkers." (The mayor has pulled back from his limited placard crackdown, disbanding the NYPD and DOT units that were enforcing the low-level corruption.)

- Consider high-occupancy vehicle policies, like those enacted after 9/11. (The mayor says would "look at" HOV lanes, which were created after the September 11 terrorist attacks and during a three-day transit strike in 2005, but have not been mandated during the de Blasio administration.)

- Expand the number of car-free busways and dedicated bus lanes to boost transit. (In June, the mayor promised to create five short busways, with a .3-mile stretch of Main Street in Flushing to be completed that month; it has been delayed twice.)

- Expand Citi Bike, prioritizing low-income and communities of color. (The de Blasio administration intentionally deprives Citi Bike of public funds and, as a result, the system's expansion into low-income communities is slow.)

- Build out the bike lane network, as proposed in the Regional Plan Association's earlier "Five Borough Bikeway" report. (The de Blasio administration's "Green Wave" plan includes a similarly complete network by 2030, but that plan has been largely shelved due to budget cuts).

The recommendation about Citi Bike comes as the bike-share system remains the only mode of transportation that has reached — and then exceeded — its pre-pandemic numbers, which it did in June. By comparison, car commuting has recovered the most of any form of transportation, regaining about 90 percent of its perniciousness by July. Subway and bus ridership remain far below pre-pandemic numbers, still off by 75 percent and 40 percent, respectively.

The RPA report comes after multiple planning agencies have put out similar lists of recommendations so that New York City could use the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to create a more resilient, sustainable city before roadways return to their normal clogged mess when the worst of the crisis has passed. Transportation Alternatives sounded the alarm early in the pandemic, and last week, the Rudin Center and Sam Schwartz put out a report with multiple recommendations for averting a carpocalypse.

I've fully embraced the need to reframe this: For a variety of reasons, carmageddon just isn't coming. What is coming is a mobility crisis that impacts everyone but falls heavily on the New Yorkers who can least afford it. It should be a strong imperative for the mayor to act but https://t.co/v51Si09hBH

— Second Ave. Sagas (@2AvSagas) August 4, 2020

Meanwhile, Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo is leading by example, converting car-choked roadways to bus- and bikeways, and encouraging more walking and transit use.