Members of Manhattan Community Board 1's Transportation Committee sent a clear message to the Department of Transportation this week: We're tired of studies on Canal Street and we want you to finally fix it.

CB1's Transportation Committee voted unanimously to demand that the Department of Transportation improve the street with things like expanded pedestrian space and an east-west protected bike lane on or near Canal.

"We are the route to get to the DOT for the community," Committee Chairwoman Betty Kay told the committee during the discussion on the dangerous street, driving home how important the community board decision would be for the future of Canal Street.

The vote came after a presentation by Transportation Alternatives volunteer Adrian Mak detailed the many problems with Canal Street, including, but certainly not limited to, a highway-width roadway, sidewalks too narrow for the many pedestrians, and thousands of crashes that have caused hundreds of injuries to pedestrians, motorists and cyclists alike.

In short, Canal Street has no place in a modern, pedestrian-friendly city, Mak said.

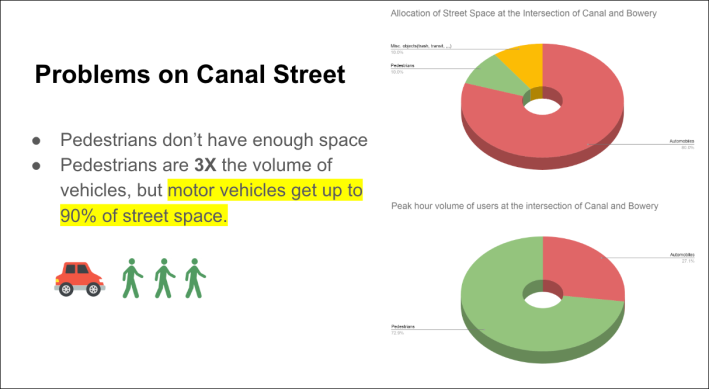

With seven lanes that are 10-to-13-feet wide given over to car traffic, Canal resembles a highway more than a neighborhood thoroughfare. Almost 90 percent of the space on Canal Street is set aside for motorists, yet at some times during the day, there are three times as many pedestrians as cars.

As a result poor design, there were 2,834 reported crashes on Canal between the Manhattan Bridge and Hudson Street from Jan. 1, 2016 to the end of 2019 — roughly two per day. Those crashes injured 109 pedestrians, 57 cyclists and 268 motorists, killing one motorist. And there is little evidence that anything will change: 2020 began with the death of a 90-year-old man who was killed crossing the street in January.

The CB1 debate veered into whether the board should make specific recommendations or merely demand that the DOT present its own ideas, but the discussion was guided by complete agreement that Canal Street was unacceptable as it currently exists.

"I was impressed by the conversation that the committee had, and primarily I was particularly impressed by [Kay's] willingness to talk about safety concerns and keep the focus on safety," Chelsea Yamada, an organizer with Transportation Alternatives said after the meeting.

The exact text of the resolution is still being worked out before the measure can be sent to the full community board, but there are many possible fixes that DOT could make, Mak said, including painted sidewalk extensions, neckdowns, an increased use of loading zones for delivery trucks, dedicated space for street vendors and some type of protected east-west bike lane.

To make any substantive changes, the DOT will have to confront its general resistance to taking space away from, and reducing the level of service for, drivers. The roadway, of course, connects the Holland Tunnel to the Manhattan Bridge — two major pieces of car infrastructure.

Some residents were pessimistic that an agency that sees its mission as primarily the movement of vehicles around the city will suddenly get enlightened about one of its worst streets. After all, the city has known about the dangers of Canal Street for decades — so there's no reason to wait, one resident said.

"I hope this doesn't become a set of decades-long studies," said Joseph Tedeschi, a longtime resident, citing a 2011 Streetsblog story that itself referenced a 2002 study on the terrible conditions on Canal. "As a community member and longtime New York City-dweller, whatever it takes to move that needle, I think there's a kind of urgency, we can all find reports looking back decades looking at the same problems."