A cyclist was killed by a driver on Thursday morning in Long Island City.

And hours later at City Hall, Department of Transportation Commissioner Polly Trottenberg was saying what she always says.

Asked about why it takes so long to build out the protected bike lane network, Trottenberg told Streetsblog reporter Julianne Cuba that money isn't the issue. The issue is all the work it takes to appease the pro-parking minority.

“I’ll reiterate the price tag is not an enormous cost,” she said, reiterating what she has said before and before. “The challenge of building out the bike network is really the labor intensive side — it’s going to local communities, it’s working through the engineering, it’s working with the businesses and residents that are at the curb. It’s going to community boards. That’s the piece that’s sort of the biggest challenge to building out the bike network.”

You know who is sick of this kind of talk? The family of Robert Spencer, the cyclist who was killed Thursday by a driver on an unprotected stretch of Borden Avenue in Long Island City — where residents of a condo building on the block demanded a safety redesign in a letter to DOT in January.

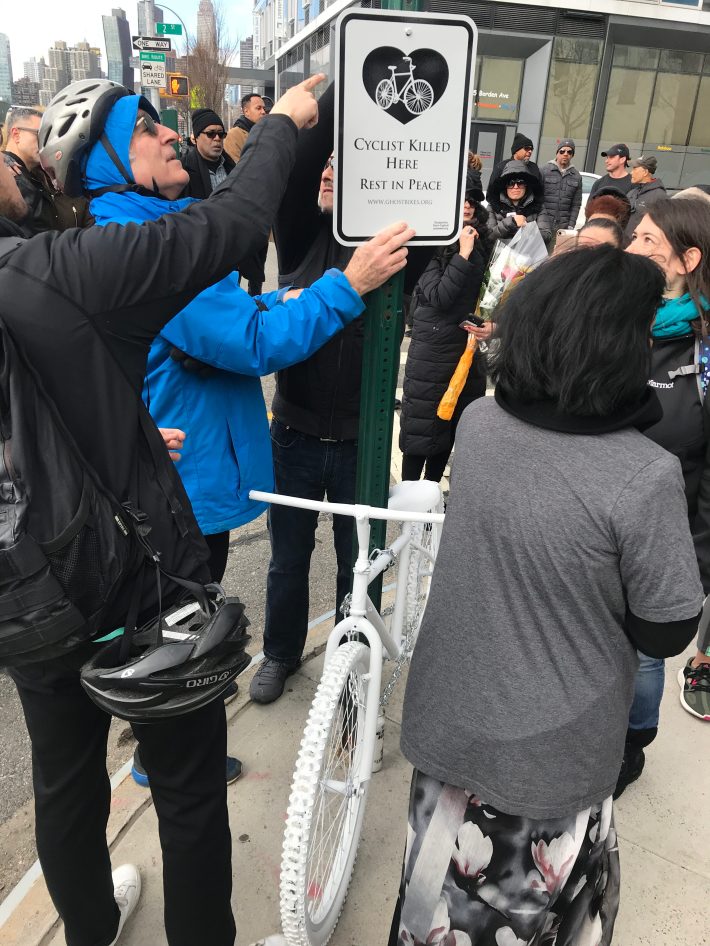

Spencer's family and cycling advocates gathered on Saturday at the crash site on Borden Avenue and Second Street to mourn his loss — and to berate city officials for not doing more.

DOT please stop wasting time with interminable presentations to the local Parking Preservation Councils and BUILD A COMPREHENSIVE BIKE NETWORK ALREADY.https://t.co/zXwemGLVyb

— Bike Snob NYC (@bikesnobnyc) March 14, 2019

"I'm outraged when I hear them say they can't build more protection for pedestrians and kids," said Nicole Spencer, the dead man's sister. "The City of New York has had cyclists for years, so don't tell me you can't keep them safe. I want my brother to be the last. We've had six cyclists killed this year. I don't want there to be a seventh."

Spencer's son, Robert Spencer III, told Streetsblog that Trottenberg's talk of "labor intensive" work should give way to action because "people's lives are being taken."

"When people are dying, that should supersede any bureaucracy getting in the way," said Spencer, who is known as TJ.

Council Member Jimmy Van Bramer and State Senator Michael Gianaris were on hand at the Transportation Alternatives-organized vigil — but neither of them spoke publicly out of deference to the family. Michael Vega, who was so close to Spencer that he considers himself his brother, made it clear that no political grandstanding would be allowed.

"These politicians answer to us," he told Streetsblog. "This death should not have happened. If any politician comes out here, let him stand and watch us silently and observe our pain. I have to live for the rest of my life knowing that Robert is dead. I'd like to see one of these politicians get into this situation. Then, suddenly, they'd be fixing these roads. Well, I'm a retired Marine. I'm not going to let this happen again, whatever it takes."

Vega was frustrated about his friend, but he could have been talking about cyclist Madison Lyden, who was killed on Central Park West over the summer or delivery cyclist Aurilla Lawrence, who was killed last month in Williamsburg. There should be protected bike lanes in both areas, but they are delayed by endless community debates.

It's understandable that Trottenberg seeks community buy-in when she proposes protected bike lanes. And there is value in having city officials go into neighborhoods and present the facts: bike lanes make roadways safer for all users, they boost local business, and they make communities more livable. It's a great message that DOT has been making for years. And the city has been building protected bike lanes at a rate fasted than during any other prior administration (albeit far fewer last year than the year before).

But...

Enough talk. The battle has been won so there's no need to keep fighting it. Council Member Antonio Reynoso was entirely right to rail on Trottenberg at a council hearing earlier this year for allowing community boards to "dictate how and when bike lanes should be built based on anecdotes and personal experiences instead of expertise."

The Bushwick Democrat wagged his finger and added, "One hundred miles of bike lanes [per year] is not impossible. It just takes movement of the DOT away from asking for permission from community boards. ... No more community board conversations. Use safety to dictate exactly what you should be doing. It's frustrating. ... You always go to these community boards, and council members give you trouble. Just stop coming to us and build them where you think they are appropriate. The Police Department would never ask a community board for permission to operate in a building if they thought drugs were being sold there. No, they just do the work because they think it's appropriate."

Since then, Council Speaker Corey Johnson has also said the city needs to defer less to community boards when lives are on the line. And there is a council bill that would mandate street redesigns whenever the city tears up a roadway. The bill, Intro 322, already has veto-proof support in the City Council, with 36 Council Members having signed on (Trottenberg opposes the bill).

Van Bramer is one of the co-sponsors of the so-called Vision Zero Design Standards bill. And he supports Johnson's call for streamlining the redesign process so that safety takes precedence over concerns about lost parking spaces or fabricated claims that bike lanes inhibit emergency vehicles. And he backs up what Reynoso said.

At the vigil, I reminded Van Bramer that he had in the past been too deferential to community board opinion — but he said he's seen the light.

"Without question, we have to completely overhaul how the city of New York and DOT handles protected bike lanes and other safety measures," he said. "It has to be driven by safety. We have clearly learned how bottled up these changes can be at the community board level, but we have to break free from how these have been done in the past and move forward. ... We need to have the political will and not be going block by block, community board vote by community board vote. The mayor has clearly done some good things on Vision Zero, but not enough. We can't have more Robert Spencers."

Van Bramer's own bike ride to the vigil offered the perfect perspective on the city's failure to keep all road users safe: He had ridden from Sunnyside to Long Island City and found himself without any protection once he left the Skillman Avenue protected lane.

"When I got to Skillman and Thomson, I had to battle it out with a cement truck, and that's horrifying," he said. "It shows that the process is broken. There are parts of the neighborhood where it is safe...but as soon as you get out of that protected lane, it is not safe at all. It's widely inconsistent. I'm riding from here to Astoria and I have to ask people what's the safest way. What we need is every street to be safe and a connected permanent network of bike lanes all over the city in every neighborhood.

"If we are going to break free of the culture that cars are first, we've got to do some radical things," he added. "Bicycles are not killing people on our streets. Cars and trucks are killing people on our street."

It's not just in New York, of course. Earlier this month in San Francisco, cyclist Tess Rothstein was killed on Howard Street — in an area where the city curtailed a protected bike lane due to community opposition. After the death, the city of San Francisco said it would add more protection. One local blog summarized it best: "It Takes a Fatality to Remove On-Street Parking."

Trottenberg's DOT says the same thing after crashes — and said it again after Spencer's death.

"DOT will look into potential safety enhancements at Borden Ave and Second Street, as we do following any fatality," spokeswoman Alana Morales said.

No more deaths. No more community boards. No more deference to people who want to store their cars in the public right of way. Make New York safe. And honor Robert Spencer's legacy.