Mayor de Blasio promises to "do more" to clear drivers from bus lanes and to build more protected bike lanes, but stopped short of endorsing a bold (and expensive) initiative from the City Council's transportation chief to create an entirely new police unit to enforce surface transit scofflaws and quadruple the mileage of safe routes for cyclists.

Council Member Ydanis Rodriguez called for the new bus lane enforcement unit on Tuesday, following up on his call last week for 100 miles of new protected bike lanes every year, but Hizzoner batted both proposals aside gently.

"On the question of enforcement, I’ve said very publicly, we intend to do more and we need to do more on bus lane enforcement," he said on Tuesday afternoon. Pressed about building 100 miles of protected bike lanes — up from an average of about 25 per year, and growing slightly — the mayor defended his prior work.

"We obviously are continuing to build a lot of bike lanes and it’s a high priority for the administration," he said. "I like to go by actions first. We have been steadily increasing the number of bike lanes including in areas as you noted earlier where there is controversy. We intend to continue. The number, the amount — we will always report what we think is needed and can be done in the time frame we have, but the directional reality is quite clear under Vision Zero."

Rodriguez told Streetsblog he'll keep fighting for more — part of his effort to rein in cars in a city that has become unlivable due to congestion and reckless drivers.

"Unless we create or expand the number of people fighting blocked bus lanes, it will be business as usual," he said. "They don't currently have a dedicated unit. We are losing millions of dollars of revenue from lack of enforcement — plus working- and middle-class New Yorkers are losing lots of time on buses stuck behind cars in the bus lane."

Slow bus trips are part of the reason for the 21-percent decline in bus ridership since 2002. Buses in New York average only 7.4 miles per hour citywide — and are so low in congested areas that their speeds approach "the speed of humans’ prehistoric form of transportation: their feet," in the words of a report by TransitCenter. In industry-leading Los Angeles — no stranger to congestion — the average bus goes 10.7 miles per hour, a big difference on a 10-mile route.

That TransitCenter report strongly called for camera enforcement, not even mentioning hiring more humans to patrol bus lanes, partly because of the high cost and partly because of the inefficiency.

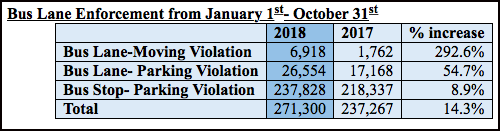

This fall, the NYPD revealed that compared to last year, it had written three times more bus lane moving violations — 6,500 from January through September this year — and 1.5 times as many bus lane parking violations (roughly 22,300 this year). Yet overall bus speeds went up only .1 miles per hour.

The reason? Experts say the number of tickets should be in the hundreds of thousands, not in the single-digit thousands.

“The number of summonses last year was minuscule,” said Jon Orcutt of the TransitCenter. “[Drivers know] your chances for getting a ticket for being in a bus stop or driving in a bus lane are still pretty slim.”

Rodriguez's call for a bus lane enforcement team is an understandable reaction to two connected failures of city and state policy: the NYPD does not devote enough dedicated resources to bus lane enforcement and the state has not given the city the power to widely deploy cameras to enforce bus lane infractions.

New York State allows the city to enforce bus lanes with cameras on only 15 Select Bus Service routes — and as a result, those SBS lines run at dramatically better speeds than regular buses or non-camera-enforced SBS routes.

Overall, cameras do a far better job than police officers. New York's speed zone cameras, for example, wrote more than 4.6 million summonses in four years, roughly ten times the amount written by the city's police personnel over the same period.

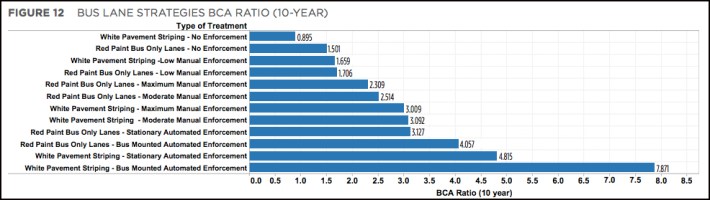

And cameras are far cheaper than cops. According to a thorough 2017 report by the National Capital Region Transportation Planning Board, the cost-benefit ratio of a regular white-striped bus lane with a bus-mounted camera is 2.6 times higher than a white-striped bus lane with maximum police enforcement effort.

Plus, a bus-camera costs only $9.500 per bus up front, plus a nominal maintenance fee, while a dedicated bus-lane enforcement officer costs $50 per hour, or more than $82,000 per year. Enforcement cameras that are mounted along bus routes are more expensive up front, but still have a cost-benefit ratio about 1.6 times greater than hiring cops to write tickets.

On the issue of protected bike lanes, Rodriguez said he was disappointed that the mayor's construction of safe routes was not likely to expand into the triple digits annually.

"Our goal is to reduce to zero the number of individuals killed by irresponsible drivers, so we need to have a plan," he said. "If we want zero deaths by 2030, we should have a goal for the number of protected bike lanes by 2030. The goal of 100 miles every year is important."

Rodriguez said it was not only about safety, but symbolism.