LOS ANGELES — They call it "the Valley of Political Death."

Congestion pricing is not an easy sell. Indeed, Governor Cuomo's strong support Thursday — and Mayor de Blasio's continuing apathy — for charging drivers a fee to enter central and lower Manhattan is a fitting symbol of what cities around the globe have experienced as they attempted to institute congestion pricing fees.

A recent panel discussion at the annual convention of the National Association of City Transportation Officials made it clear that challenges ahead are huge — as, indeed, they were last year when Governor Cuomo backed congestion pricing only to do nothing to get it through the legislature during the last session.

Polls show that politicians (60 percent) support congestion pricing far more than the public (42 percent), said Daniel Firth, who has consulted congestion pricing cities such as London and Stockholm.

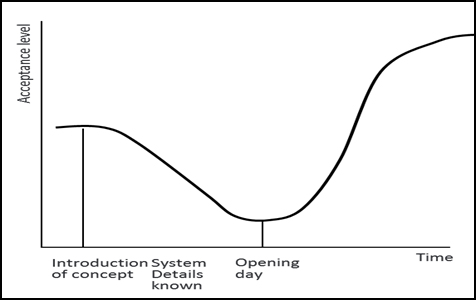

And public approval of congestion pricing is at a peak when the concept itself is introduced — as it was under Mayor Bloomberg a decade ago. That approval rating, however, tends to drop week by week as the nuts and bolts are figured out, until public approval reaches its lowest point at the moment of implementation.

"That's 'the Valley of Political Death,'" Firth said.

The good news for politicians is that public approval tends to rise — rise even higher than its initial support — in the weeks, months and years after the system goes into effect.

"People realize it's not nearly as bad as they thought it might be," Firth said.

And the public does understand the concept of a tax on drivers to fund public transit, as New York's congestion pricing program would, added Washington, D.C.'s DOT Director Jeff Marootian.

But the notion of a political Death Valley is difficult for politicians, so they need to suck it up, Firth suggested.

"The public often thinks the status quo is fine and anything we do will be worse," he said. "We need to question that" because public approval does rise in the end.

New York itself is grappling with that very issue as Cuomo and de Blasio appear on yet another collision course, with the governor declaring that congestion pricing is "the only real answer" and "the one solution" to fund transit, and the mayor still believing congestion pricing is a regressive tax. (Former Daily News City Hall reporter Erin Durkin openly mocked Hizzoner for his stance, calling him a "very affluent man who views himself as an average middle class guy.")

Governor Cuomo says @ABetterNY event that congestion pricing is the only real solution to MTA funding and commits to getting it done. pic.twitter.com/yufwnKiYiZ

— Ya-Ting Liu (@yating_liu) October 4, 2018

Shoshana Cohen of Portland, Oregon's Bureau of Transportation, said she'd heard that argument before — and rejected it.

"It's hard to pay for something that is currently free," she said. "And it's hard to believe that pricing will help relieve congestion. And people like driving. Our system is set up around driving, so it's easy for people to get into their cars." (Or, like Mayor de Blasio, be driven in one to get to gym 45 minutes away.)

The central issue of congestion pricing, panelists agreed, was, indeed, the notion of "equity." Studies show that the well-to-do are far more likely than lower-income residents to drive into Manhattan, so it seems equitable that the rich should pay for the reduced congestion they would enjoy while funding public transit to also allow the less-fortunate to get to work easily.

In calling congestion pricing "regressive," Mayor de Blasio has apparently not chosen that view of equity, which is why I asked the panel about the word itself.

I'm confused by the term "equity." We know that richer people drive more. We know that owning a car is ultimately more expensive than mass transit. And we know that cars are taking a huge toll on our public health, so how come opponents — and even some supporters — of congestion pricing say it's inequitable to tax the rich to support improvements for the less rich?

"Cities need to have a good discussion of what equity means because people are talking past each other," Firth said, perhaps foreshadowing the Cuomo-de Blasio battle. "We need to focus people's minds on the real equity: the equity of the entire system."

That's a challenge even for supporters of congestion pricing. In a recent interview with Streetsblog, soon-to-be-State Senator Alessandra Biaggi — who defeated congestion pricing staller Jeff Klein in the September primary — suggested that her strong support for a tax on driving was already wavering.

"I support it being progressive," Biaggi said. "If you are a working person, a senior or a student and driving in during those peak hours, you can still be able to afford it. At the end of the day we don't want to box anyone out who needs to be in the city."

I pushed back on Biaggi's notion of a carve-out for "working people," given that everyone who drives into Manhattan could make the argument that he or she is doing it for "work." She replied by suggesting an income level at which congestion pricing would kick in — another questionable concept, given how easy it would be to game that system. It's also questionable about why politicians would focus on the supposed wave of low-income drivers entering Manhattan when studies show it is a tiny number of people.

Washington D.C. tried a different approach, raising the cost of parking rather than tolling drivers to enter the business district of Penn Quarter/Chinatown. In a pilot program, the district discovered that increasing the cost to store a car on the curb reduced double-parking by 43 percent, reduced cruising for parking from 15 percent to seven percent and reduced the amount of time to find a spot from six minutes to two minutes.

It was interesting to note that New York City DOT Commissioner Polly Trottenberg, who was not on the panel, but was a mere spectator like this reporter, asked Marootian for more information about this success, suggesting a way forward for her agency if the mayor doesn't back the governor's larger congestion pricing scheme.

Editor's note: The bulk of reporting for this story was done at the NACTO convention in Los Angeles, with additional reporting from New York.