Hundreds of thousands of speeding scofflaws will simply get away with it because the NYPD simply cannot fill the enforcement gap that opened Wednesday as the city's speed cameras were ordered turned off by the state legislature.

Just 140 school-zone cameras issued more than more than 4.6 million tickets since 2014, while the NYPD's tens of thousands of officers issued 519,372 over the same time period, according to city data. Nonetheless, as the cameras went dark on Wednesday, NYPD Chief of Transportation Thomas Chan told Streetsblog through a spokesman that his division "is prepared to focus precinct Traffic Safety teams towards conducting additional enforcement ... in priority areas."

The department said that 2,448 police officers and 364 radar guns have been added since 2014, allowing the Department to write 149,910 in 2017 as opposed to 117,768 in 2014, a small increase compared to the millions of tickets issued by speed cameras during the same period. "These resources are sufficient to quickly step in and address any uptick in motorist speeding," the statement continued.

They are, in fact, not.

"NYPD has said they will see what they can do, but they have also said they have a lot of needs for their resources and they can't completely cover what this automated system does," Department of Transportation Commissioner Polly Trottenberg said at a press conference on Wednesday, accepting the reality that humans cannot do what speed cameras can.

The Patrolmen's Benevolent Association, the NYPD rank-and-file union that opposed the extension of the camera program, basically agreed with Trottenberg, saying that the NYPD's existing staff is no match for the cameras — and that's a good thing.

"We’d prefer to see more officers hired," PBA spokesperson Al O'Leary told Streetsblog.

As the debate raged in Albany about the city's school-zone cameras, the PBA consistently said officers are better at traffic enforcement than cameras — even as union President Pat Lynch basically admitted his members don't like doing traffic enforcement. On Wednesday, he added that catching speeders and saving lives is not a goal in and of itself.

"(Cameras) cannot do the job of a live, professionally trained police officer who, having stopped a speeder, may make an arrest for driving under the influence, driving without a license or insurance or even worse offenses like carrying an illegal weapon," Lynch said. "We view traffic enforcement as an opportunity to take the dangerous drivers and criminals off the road that a camera can’t."

It is certainly important to remove serious offenders from the roadways, but the speed camera program saw the reduction of speeding itself as its own equally important mission. Since 2014, cameras have done that nine times better than uniformed officers.

The cameras work, too: Speeding dropped 63 percent in areas where they've been installed, and more than 80 percent of speeding drivers caught on camera don't do it again.

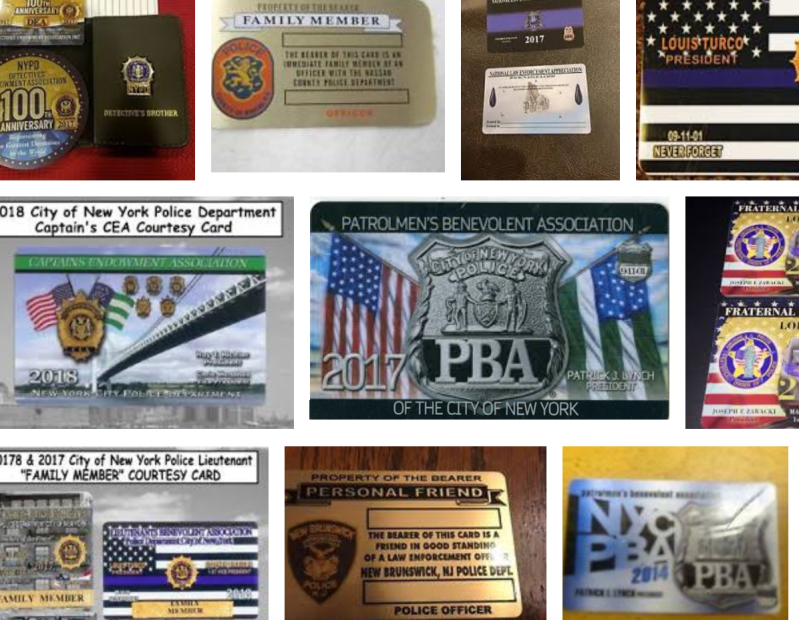

The real incentive for the PBA here is its members, who notoriously let each other — and their buddies — off the hook for speeding and other traffic violations.

PBA is the only notable organization that opposed extending and expanding the speed camera program. Its members' donations also filled the coffers of Governor Cuomo, Senate Republicans, and Democrat-in-Name-Only Simcha Felder, who stubbornly refused to let the bill out of his committee despite it having a majority of votes to pass on the senate floor.

Speed cameras began being turned off on Wednesday, though 20 mobile units will remain active through August, when they, too, will be shut — unless the State Senate reconvenes and passes an Assembly bill that would reauthorize them and double their number.

Senate Majority Leader John Flanagan said that won't happen.