With the momentum for a New York City congestion pricing plan in danger of dissipating into an Uber fee, it’s worth revisiting first principles. Any vehicle that takes up space in the jam-packed Manhattan core imposes sizable -- and quantifiable -- congestion costs on everyone else using the streets to get around.

New York needs congestion pricing because these costs are enormous, and in this post I propose a new and more accurate way to measure them.

Congestion causation is customarily framed as the aggregate slowdown of vehicles in motion caused by one additional vehicle trip. That’s how I assessed the costs of car travel when I was developing my Balanced Transportation Analyzer in 2010.

I estimated that a single car journey from the suburbs to the Manhattan Central Business District effectively stole as much as $160 worth of time from other vehicles combined. The majority of that congestion cost occurred not in the CBD but on the miles of crowded highways leading to and from Manhattan, where most CBD-bound commuting takes place.

That calculation garnered a headline or two, but it needs to be updated for the age of Uber. For-hire vehicles now account for around 50 percent of mileage in the Manhattan CBD — up from 42 percent just six years ago. The rise of app-based services also brings a non-mileage dimension to gridlock, because drivers spend more time sitting and waiting for passengers to appear or their app to ping, as industry expert Bruce Schaller documented recently.

Given these shifts, we need a frame that zeroes in on the Manhattan CBD and couches congestion causation in terms of the time that vehicles spend on those streets, rather than the mileage.

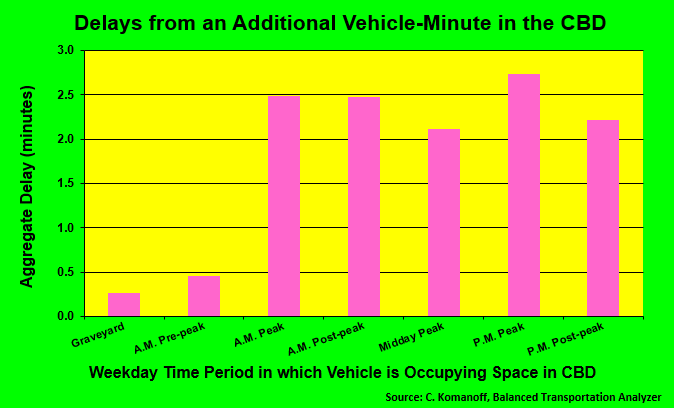

Well, I’ve made the calculation, and the chart below sums up the result: With the exception of overnight hours, each minute that a vehicle is snaking through the Manhattan core is prolonging similar vehicle trips by a total of 2-2½ minutes. In effect, “my” vehicle’s occupation of Manhattan street space acts as a force multiplier of lost time for other vehicles on Manhattan streets.

Like any congestion metric, this one comes with qualifications. Because it draws mathematically only on vehicles in motion, it necessarily overstates the congestion attributable to a vehicle standing at or near a curb. It also overstates smaller vehicles’ congestion causation since the vehicle mix that gives rise to my model’s underlying speed-volume equation includes trucks and buses that take up more space. On the other hand, my metric doesn’t count time losses imposed on people walking or biking. And my figures are keyed to NYC DOT’s most recently published traffic speed data for the Manhattan core, which are from 2015 and don’t reflect reported declines for 2016 and 2017.

With these caveats, the new congestion metric provides another lens to evaluate Schaller’s proposal to charge Ubers and other app-based vehicles up to $50 per hour of “residence” in the hyper-congested heart of Midtown during peak weekday hours.

I’ve estimated that the average value of time for vehicles in the Central Business District — reflecting the actual mix of cars, yellow cabs, app-based vehicles, vans, buses, big rigs, and other trucks — is around $49 per hour. Let’s call it $50.

A $50 per hour charge would be justified, then, if that hour of residence by an Uber slowed down the mix of vehicles by an hour. In actuality, the aggregate slowdown is two hours or more; and that’s a CBD average; the congestion causation rate is far higher in Midtown alone.

Of course, congestion costs decline as gridlock is abated, so the price should be set well below the peak cost. On balance, Schaller’s $50 top price is in the right ballpark.

But the ballpark is bigger than just Uber. Let’s take a look at car trips to the CBD by Sally from Scarsdale or Sal from Sheepshead Bay. Within the CBD, one of those trips might cover three miles round-trip. At 8 mph, a tad below the 2015 average, those three miles take 22.5 minutes, and that imposes 45-60 minutes of lost time on all other vehicles. Multiply that by the $49/hour average value of vehicles’ time, and the CBD portion of this single car commute imposes $35 to $50 of time costs on other travelers in vehicles. That easily warrants the $11.52 peak-hour entry charge proposed by the Fix NYC panel.

Numbers aside, the main takeaway from this exercise should be that every vehicle occupying space on New York’s most congested streets should be charged for taking time from the “commons” of other people traveling. True, a “binary” cordon fee (you either pay all or nothing) is unsubtle and should evolve into a charge to drive per-mile and/or per-minute. And of course for-hire vehicles, which have GPS and are subject to regulatory authority, could be surcharged per-mile/minute in the taxi zone without too much trouble (an improvement over the one-time surcharge on “the drop” as Fix NYC proposed).

But no vehicles merit exemptions from the fees and surcharges. Ubers are exacerbating congestion, but every vehicle in the Manhattan core compounds it.