When Larry Gould was working in MTA transit planning and operations in the 1980s, he pitched the idea of buying train cars with "niches" -- small spaces to the side of train doors that riders can fit into to clear paths for people getting off and on, speeding the boarding process.

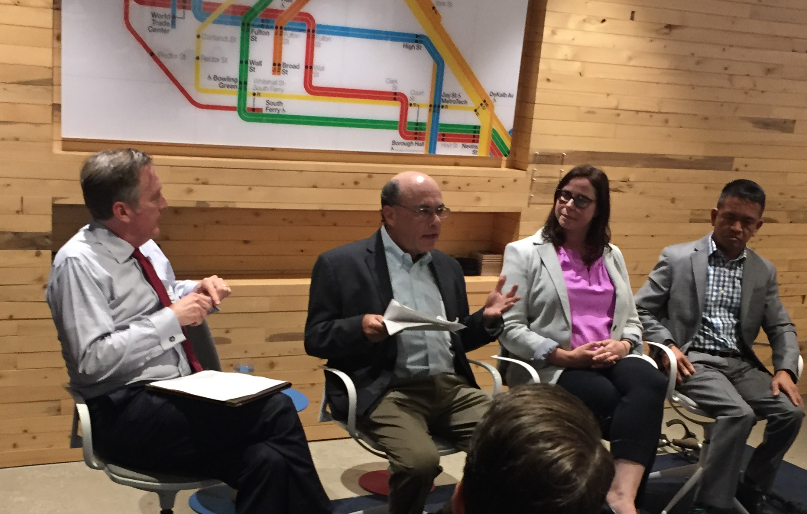

"I remember trying to sell it, and trying to explain it, and I said, 'Well, they have it on the PATH cars,'" Gould, now a planner at NelsonNygaard, said last night at a TransitCenter panel featuring former MTA staffers. "There was nobody at the table who knew what the PATH cars looked like."

It was a reflection of the agency's insularity that sheds light on New York's transit troubles today. The MTA may have talented staff, but the changes needed to modernize and improve train and bus service are routinely stifled by a risk-averse internal culture that doesn't place a high value on promptly adopting best practices in the transit industry.

Cities like Paris, London, and Zurich may have figured out how to build transit capital improvements more efficiently than New York. But at New York City Transit, Gould said, "It's not part of your training... to know what they're doing in Zurich or London or Paris."

Gould was joined by Sarah Kaufman and Chris Pangilinan, who both left the MTA after determining they could do more to provoke change from the outside. They described a workplace with no shortage of talent or ideas, especially among younger staff, but encumbered by hesitant middle management, an old boys club culture straight out of the "Mad Men" era, and overbearing political leaders.

Kaufman, who worked at the MTA from 2006 to 2011, said she struggled to get open data policies and social media communication strategies up and running. She eventually made breakthroughs, including the launch of the Weekender app and the opening of MTA bus and train data to developers, but she had to swim against the current the whole way.

"It took reaching out to people individually to eventually to get this thing going, and then it took volunteers, who really bubbled up from junior staff, to say, 'I want to do this,'" she said. By the end of her stint, she was spending 80 percent of her time struggling to get colleagues and superiors to buy into her ideas, she said.

While Kaufman was fighting for open data, Pangilinan was working at the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, releasing whatever data he wanted without conflict or fear of retribution. Pangilinan later spent two years at the MTA working on rail planning and bus data, where management was far less willing to let staffers take such initiative.

"A lot of this conservatism comes from a fear of what's going to happen from the person above you -- all the way to the top," Pangilinan said. "You could just tell that [managers] were struggling with their hands behind their back, and they were grimacing to say no to me to release data or to try something new."

When change does happen at the MTA, it's usually due to the alignment of younger staff and top executives, the panelists said. Kaufman credited former MTA Chair Jay Walder for breaking the logjam on open data and supporting the reforms she was trying to bring about. "There was a lot of resistance all along the way, but when the ideas came from the bottom, and the initiative came from the top, things actually happened," she said.

The panelists offered a few recent changes as evidence that motivated MTA staff are looking out for riders and able to steer the ship in a better direction. Gould cited the recent elevation of easy-to-understand measurements of subway performance over older, less-accessible metrics as an encouraging sign.

Advocates can help buoy MTA staff pushing for internal reforms by providing external political support. "Look for small wins and take advantage of those," Pangilinan said, citing the Staten Island bus network redesign and the continued rollout of Select Bus Service. "We've got to celebrate that and support it, and not let those initiatives get watered down."

At the same time, the power of the governor to shape the agency's culture and let the MTA's best people flourish can't be overstated. A generation ago, when the MTA was emerging from its low point of disinvestment, agency chiefs like Robert Kiley and David Gunn were willing to take risks to rescue the system from near-collapse. They were given the leeway to do so by the political leaders of the time, said Gould.

"Kiley and Gunn had unequivocal support from their political handlers, whereas the current staff has unequivocal oversight from their handlers," he said. "The situation [in the 1980s] was so desperate that you basically had to give it to people and fully empower them."