Andrew Cuomo may or may not be serious about enacting a congestion pricing plan for New York City, but by putting the idea out there, he has forced Bill de Blasio to clarify his position.

Every time de Blasio gets asked about congestion pricing, he retreats to the rhetorical haven of calling it "unfair." Most recently, in the Democratic primary debate, the mayor said the Bloomberg administration's 2008 congestion pricing plan was "very unfair to the outer boroughs" and that the current Move NY toll reform plan "still doesn't address a host of equity issues."

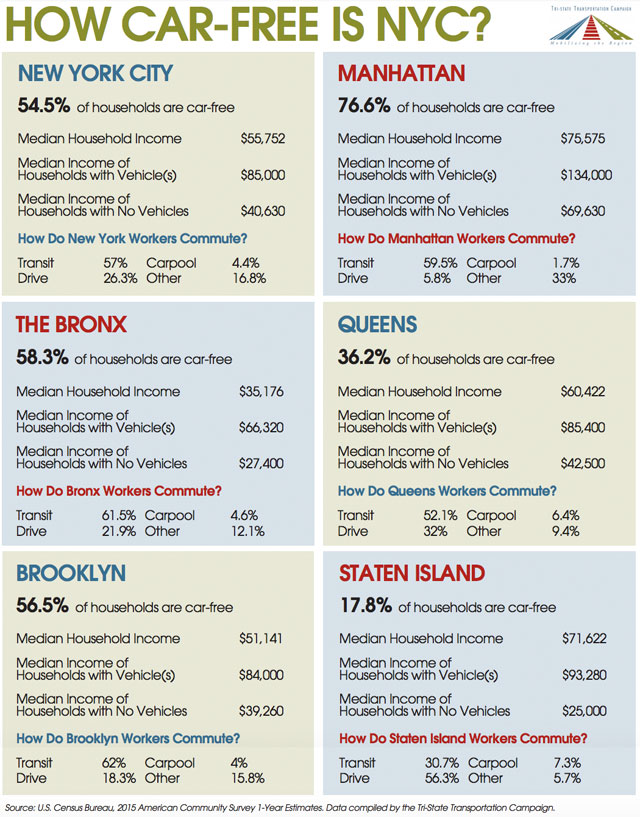

Charles Komanoff and, more recently, the Daily News editorial board have pushed back against the notion that Move NY is unfair to the boroughs besides Manhattan. I want to push back on another common but incorrect assumption de Blasio is propagating: that congestion pricing is unfair to poorer New Yorkers.

The Move NY toll reform plan, which would put a price on driving into Manhattan below 60th Street and add surcharges to for-hire car trips where they are most in demand, is a powerful tool to address one of the great inequities in NYC's transportation system: the time penalty that affluent people in cars impose on less affluent people riding the bus.

There are two major trends shaping travel on NYC streets right now, and they're intertwined. One is the increase in traffic and congestion in the Manhattan core, and the other is the decline in bus speeds and ridership.

Between 2010 and 2015, average citywide bus speeds fell 2 percent, contributing to a long-term decline in bus ridership. Over the same period, average general traffic speeds in Manhattan below 60th Street fell 12 percent, according to NYC DOT. Congestion is slowing down buses in a vicious cycle that's only picked up more momentum in the last few years.

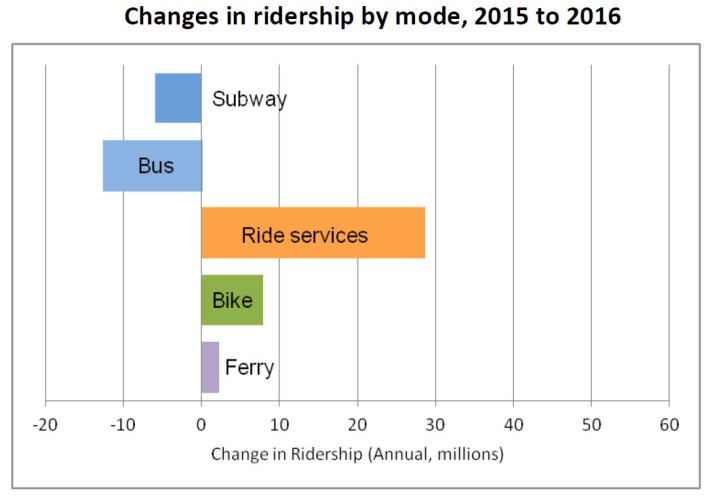

Since mid-2015, the number of for-hire trips in NYC has skyrocketed, propelled by "transportation network companies" like Uber and Lyft. From 2015 to 2016, TNCs caused a net 3 to 4 percent increase in citywide traffic and were responsible for a 7 percent increase in traffic in Manhattan, western Queens, and western Brooklyn, according to research published by Bruce Schaller earlier this year. The more people opt for the personal convenience of an Uber or Lyft, the slower the buses go.

So far in 2017, bus ridership has fallen another 2 percent compared to the previous year. People who can afford a $10 or $20 Uber ride are slowing down people who can afford a $2.75 bus fare.

Move NY addresses this inequity by both pricing car trips across a cordon around the Manhattan core and adding a surcharge to for-hire trips in Manhattan roughly below 96th Street. It creates a fundamentally fairer transportation system, where bus riders have access to faster, more reliable service.

Improvement in bus service is one of several reasons that Move NY would have a progressive net effect, including the fact that it would transfer revenue from relatively affluent car owners to services that poorer car-free households rely on. The street space that road pricing opens up likewise makes it easier to repurpose traffic and parking lanes for transit, biking, and walking, benefitting New Yorkers who can't afford cars. And it's never been particularly fair that every transit trip in NYC carries a price, but driving into the congested heart of the city is free.

If fairness was a guiding principle for de Blasio's transportation policy, his administration wouldn't be spending hundreds of millions of dollars on ferries for a small number of relatively affluent waterfront residents, or handing out 50,000 parking perks to a favored political constituency, or taking its sweet time with bus service improvements that should be an urgent priority. Toll reform and congestion pricing, on the other hand, would be on the agenda.