The news that Sandy-related repairs will require closing one or both directions of the L train under the East River (the “Canarsie Tube”) for one to three years has understandably caused panic among the estimated 230,000 daily passengers who rely on it. Businesses in Williamsburg that count on customers from Manhattan are also concerned about a significant downturn in sales. When the Canarsie Tube was shut down on weekends only last spring, it was bad enough for their bottom line, and this will be much worse.

Fixing the Canarsie Tube is imperative, but it doesn’t have to result in a massive disruption that threatens people’s livelihoods. The key to keeping L train passengers moving is to create new, high-capacity bus rapid transit on the streets.

Since the potential closure went public, several ideas have been floated to mitigate the impact. None of them do enough to provide viable transit options for L train riders. Only setting aside street space for high-capacity BRT can give riders a good substitute for the train. This can be done in time for the impending subway closure while also creating long-term improvements that address surface transit needs in northern Brooklyn much better than a waterfront streetcar ever could.

The Inadequacy of Current Proposals

While some L passengers will be able to switch to other subway lines, a huge number will face significant inconveniences. Passengers from Bedford Avenue to Union Square, for example, will face up to three new transfers.

For these passengers, a few ideas have been suggested: The MTA could provide shuttle buses to the J/M/Z, as was done during last year’s temporary closing. Or there could be shuttle buses over the Williamsburg Bridge, perhaps in dedicated lanes.

Providing enough shuttle buses to serve such a massive number of people is a grim prospect. The shuttle to the J/M/Z last spring was very inconvenient, and even if there were a shuttle with dedicated bus lanes over the Williamsburg Bridge, the streets between the L train and the bridge will still be jammed with slow-moving buses. Upwards of a hundred thousand daily passengers who used to zip between northern Brooklyn and Manhattan will suddenly face a chaotic transfer and a torturous bus ride. Many commuters who have the option of driving will simply get into their cars.

What Should We Do Instead?

The closure of the Canarsie Tube could be addressed by a temporary solution, but the problems on the L are not temporary. Sandy is unlikely to be the last major storm to damage our tunnels. And as more and more development comes online, the crush loads on the L will get worse and some people will start opting to drive.

Indeed, before the big L train news, the developers at Two Trees were already looking into a Brooklyn-Queens waterfront streetcar to provide additional transit access for the massive influx of residents and jobs. That proposed streetcar would travel up and down the waterfront at speeds slower than the existing B32 bus, which carries only 600 daily passengers. It wouldn’t provide a connection into Manhattan where far more people want to go.

The city and the MTA can address the L train closure and the transit access problems by the Brooklyn waterfront at the same time by building world-class bus rapid transit.

This BRT solution would go beyond what New York has done so far with Select Bus Service (SBS), which brought benefits mostly through off-board fare collection. The SBS toolkit will not be sufficient to handle the huge number of stranded L train riders. To move all those passengers without creating a busjam, the full arsenal of BRT elements needs to be deployed: a fully dedicated busway that can’t be impeded by deliveries or drivers turning right, stations level with the bus floor, off-board fare collection, and more.

Here are the main components of a BRT solution to the L train closure:

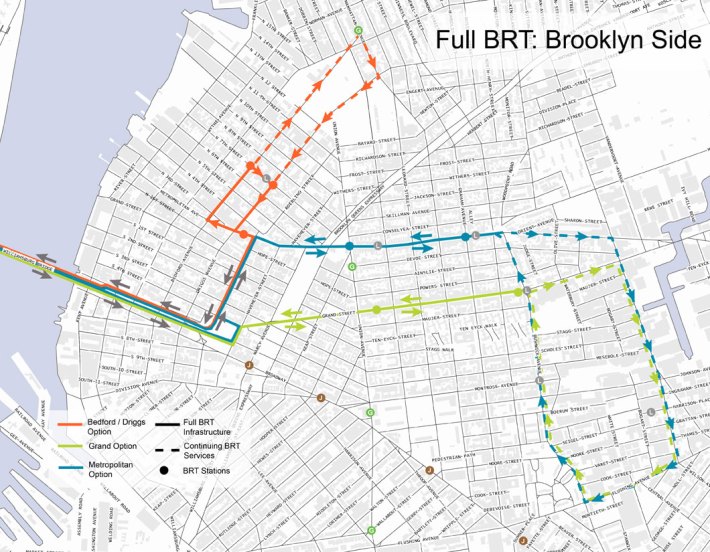

Connect to L Train stations via fully dedicated BRT lanes. While a specific routing needs further study, a bike/ped/transit mall down Bedford, perhaps as a one-way pair with Driggs, is appealing. Bedford is already overflowing with pedestrians who could use more space, and when closed to traffic for Williamsburg Walks on three Saturdays each year, it has experienced few problems. Because Williamsburg in that area is a grid, there are several good alternatives for diverting traffic. One landmark station with off-board fare collection, and a free transfer to the L (ideally a physical connection so all those passengers are not double-swiping), could be built at Bedford and North 7th (and Driggs in the other direction) with another station at Metropolitan to avoid overcrowding and to shorten the walk for many passengers coming from the waterfront. Maybe the community can stomach sacrificing a few hundred parking spaces to improve the daily trips of 230,000 former L train passengers. Full BRT might also be considered along Metropolitan Ave to connect both the Lorimer and Graham L stations to the bridge access routes, or on Grand Street, providing a straight shot from the Grand St. L stop onto the Williamsburg Bridge. Trucking would be restricted to the arterial that did not have BRT.

Brooklyn connection to the Williamsburg Bridge. In the short term, BRT vehicles could access the bridge from a dedicated busway on a short section of Roebling (between Metropolitan and the bridge) or Borinquen, depending on how the busway connects to the L, and would exit the bridge (also on the Brooklyn side) into the existing terminal at the foot of the bridge. In the long term, dedicated access ramps to the center lanes of the Williamsburg Bridge would be needed to fully bypass the bottleneck.

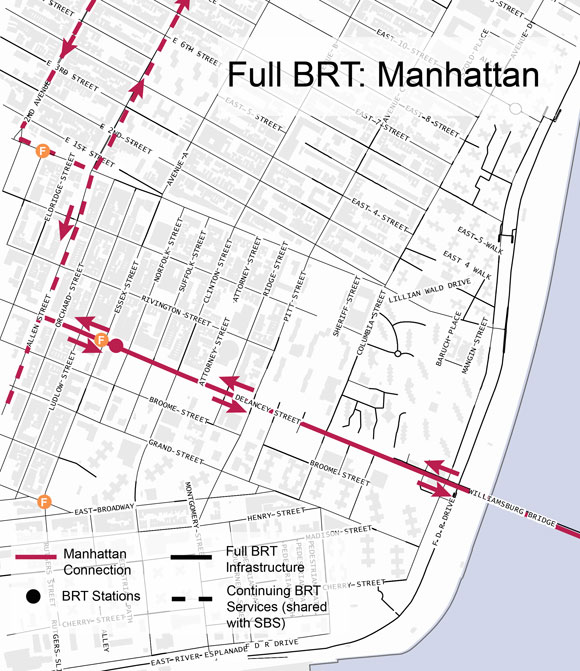

Connect to Delancey/Essex Station and Allen Street SBS. On the Manhattan side, BRT vehicles would run on a central median-aligned busway on Delancey with a station at Essex to connect to the Delancey/Essex Street F/J/M/Z trains. Many passengers would transfer into the subway system there. But it would be a missed opportunity to not continue the busway to Allen Street and provide direct connections into the M15 SBS which operates two-ways on Allen Street. Some buses could make the turn and continue north (up First Avenue) or south (to the Financial District) while others may turn around and head back to Brooklyn.

In Brooklyn, extend the Bedford service to the Nassau G. With BRT, even when the dedicated lanes end, the services can continue. Ideally, a dedicated busway on Bedford could be extended north to the Nassau Avenue G station. Even better, the full bike/ped/transitway could be extended like this. But even with the L train East River closure, we cannot expect taking road space to be a snap. At the very least, we should extend the BRT service to the north in mixed traffic, beyond the Bedford L station, to the Nassau G Station. This will cut out the need for the one-stop transfer from the G to the new BRT route and will speed up the trips of many people who currently rely on the G. This benefit will also outlast the Canarsie Tube closure.

Only true BRT has the capacity to carry the 230,000 daily trips the East River L train tunnel currently handles and be built in the timeframe we are talking about. If designed right, BRT could make the trip significantly faster than the multiple-transfer subway alternatives.

The proposal could also help address the growing transit needs of the Brooklyn waterfront, most of which are Manhattan-bound rather than Red Hook-bound. It would provide a new, long-term alternative to the L’s 14th Street routing, helping to address the overcrowding problem. The closure of the Canarsie Tube could actually be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for New York City to grab some street space and build high-quality surface transit.

Walter Hook and Annie Weinstock are principals of BRT Planning International, a boutique WBE planning firm that specializes in BRT projects around the world.