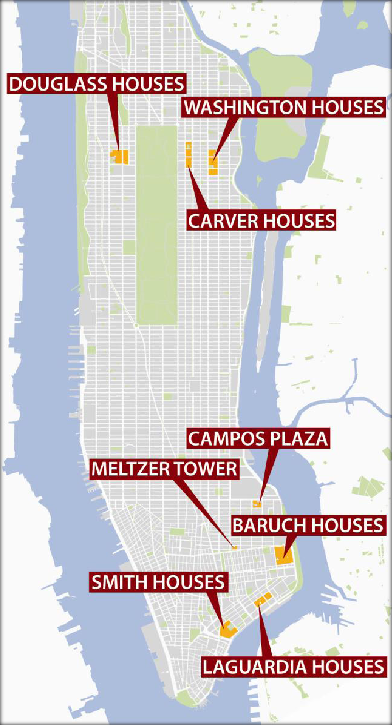

It's easy to see why the New York City Housing Authority's recent proposal to develop new housing on some of its property in Manhattan has aroused strong passions.

Under the proposal, NYCHA would enter into 99-year ground leases with developers to build new residential buildings at eight properties in Manhattan below 110th Street. Most of the new units -- 80 percent -- would be market-rate, while 20 percent would be income-restricted. Developers would also be asked to install upgrades to the existing properties. NYCHA's main reason for pursuing this plan is that the land-lease rental revenue from the developments -- up to $50 million per year -- would fund capital improvements to NYCHA buildings, repairing things like roofs, elevators, and heating systems. Meanwhile, the angle that's getting a lot of play in the press is "luxury condos replace public housing playgrounds."

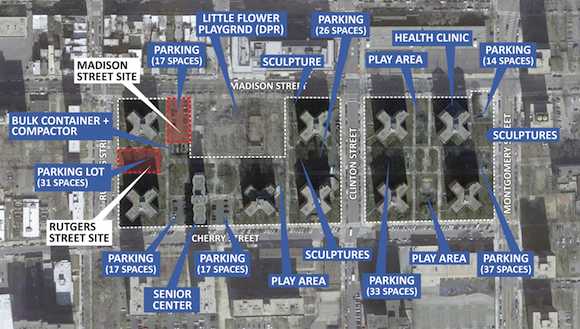

While it won't completely make up for decades of declining federal support for NYCHA, and it would fill only a portion of NYCHA's maintenance needs, the plan deserves consideration. New developments could replace space on NYCHA properties currently devoted to subsidized surface parking, without any net loss of park space or other community facilities. But so far, both the agency and its residents have shown a reluctance to reduce the amount of low-cost parking for NYCHA residents.

The new developments would go up on land currently occupied by a total of 632 surface parking spaces, as well as a community garden, a basketball court, a baseball field, two tree-filled spaces, two trash compactors, and a community center.

NYCHA says that the project will "replace or reconfigure impacted areas (i.e. seating areas and gardens) where space is available." At most sites, this space is already available. At least 500 surface parking spaces would remain untouched in the development plans. To help address resident concerns about lost recreational space, NYCHA could specify in its plan that parking lots would be replaced with green space or community facilities.

Problem solved, right? Residents keep the same amount of green space, while new development helps fund needed maintenance.

But at community meetings where NYCHA has presented the proposal, a common theme has emerged from both the authority and its residents, though they remain locked in conflict: protecting the perk of subsidized parking.

"They're trying to push this down our throats," said Harvey Epstein of the Urban Justice Center at one public meeting about the proposal. "They said they're going to relocate the parking lot. Where are you relocating it to?"

"They should have already mapped out beforehand the alternative places for people to park," said Bobby Forestal, a lifelong Douglass Houses resident, at another meeting.

NYCHA's Margarita Lopez "reassured residents repeatedly that no resident parking spaces would be lost and that new parking locations would be in place before construction began," according to DNAinfo. Although most low-income public housing residents can't afford the luxury of maintaining a car in Manhattan, NYCHA offers annual parking permits to its tenants for as little as $60 per year, far below the cost of nearby garages. Apparently the agency is committed to maintaining this perk, though it's not exactly clear where.

Six of the eight development sites are located in the part of Manhattan where zoning sets parking maximums for new construction. In addition, a zoning change moving through the approval process would remove perverse parking mandates for affordable housing. As a result, most of the new construction being proposed will probably not be required to provide parking.

Despite the emphasis on maintaining discount parking for Manhattan public housing residents, there are positive elements to the proposal.

Most NYCHA properties are mid-century tower-in-the-park developments that, while providing spacious grounds, tore apart the neighborhood fabric of the city blocks they replaced. By filling some of the gaps in the superblocks, these new developments can help right an urban design wrong. In fact, NYCHA chose development sites "along street fronts to encourage pedestrian traffic and campus integration with the neighborhood."

In addition, adding residential units in areas like Manhattan with access to employment centers is good housing policy. One-fifth of all the new units would be income-restricted, matching the city's inclusionary zoning standard.

This isn't the first time the space around New York's mid-century tower-in-the-park housing complexes have been considered for new development. A low-cost resident parking lot at Elliott-Chelsea Houses was redeveloped as housing, and a recreational area at Soundview Houses is set for new affordable housing. On the Upper West Side, space within Park West Village was redeveloped with new retail and residences. In Brownsville, a proposal from non-profit Community Solutions would build affordable housing on open spaces within existing NYCHA properties.

The RFP for the Manhattan proposals is set to be issued at the end of April. Until then, there is time to improve the plan so it better meets the needs of residents, and not parked cars.