Last week, the city's Independent Budget Office released a report on the MTA's revenue structure [PDF] which has been getting a bit of play. At Second Avenue Sagas, Ben Kabak focused on the report's main thesis: that the volatility of dedicated taxes and fees threatens the financial stability of the transit agency. Steven Higashide of the Tri-State Transportation Campaign picked out a graph showing that the recently enacted payroll mobility tax already makes up 30 percent of all dedicated revenues, or around one-eighth of all operating revenue.

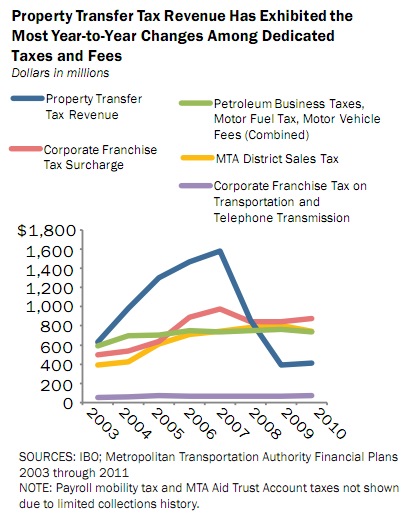

He also highlighted the graph on the right, which jumped out to us. It shows the extent to which the difference between the MTA's flush budgets of 2007 and the painful cuts of today is attributable to the catastrophic drop in a single revenue stream: property transfer taxes. Those taxes brought the MTA $1.58 billion in 2007 but only $389 million in 2009.

As Gene Russianoff told Streetsblog before the crash, the heady days of the real estate boom masked underlying weaknesses in the MTA's budget. When the economy plunged into the worst crisis since the Great Depression, in one fell swoop the MTA lost more than a billion dollars in revenue every year. Almost every dollar brought in by the payroll tax is being spent just to patch up the hole left by falling real estate taxes.

The scale of that drop lays bare how the standard excuse for opposing additional transit funding -- cries of "waste, fraud and abuse" at the MTA -- misses the mark. Comptroller Tom DiNapoli has been steadily auditing segment after segment of the MTA's operations. In his first eight audits, his office found $296 million in wasteful spending and unrealized opportunities [PDF]. That's worth some attention, but still equates to only a quarter of the decline in revenue from the property transfer taxes.

DiNapoli's most recent audit of the MTA, done jointly with City Comptroller John Liu, found all of $10.5 million in wasteful spending on construction during off-peak hours. (It also identified how the MTA might be able to reduce the time that service is disrupted while repairs are underway.) The report came out just days after the MTA released a capital budget which relied so heavily on borrowing that transit riders can expect to pay hundreds of millions of dollars in additional debt service each year before the decade is out.

When politicians like Long Island Republican Lee Zeldin point to DiNapoli's reports and claim that another billion and a half dollars in payroll taxes could be cut from the MTA each year by targeting "waste and inefficiency" without leading to fare hikes or service cuts, it's beyond wishful thinking. It's delusional.