And the cycle continues.

Mayor Mamdani and the City Council are blaming each other for failing to implement a 2024 state law that gave the city the power to lower speed limits — and in doing so are following a pattern of inaction set by their predecessors even as tens of thousands of New Yorkers have been killed and injured by speeding drivers since the law's passage.

As candidates for the respective offices, both Mamdani and new Council Speaker Julie Menin professed strong support for reducing the speed limit to 20 miles per hour to increase the safety of city streets.

But like then-Mayor Adams and then-Council Speaker Adrienne Adams, both parties are saying the other party is responsible for full implementation of "Sammy's Law" — as the bill was dubbed to honor Sammy Cohen Eckstein, a 12-year-old boy killed by a driver on Prospect Park West in 2013.

Mayoral spokesperson Sam Raskin repeated the Adams administration's claim that the City Council must pass a law to lower the speed limit citywide, and that the mayor — who vowed on the campaign trail to "fully implement" Sammy's Law — can only reduce the speed limit on select corridors.

"DOT is continuing to identify more corridors where safer speeds can save lives," Raskin added. "The administration has been preparing to use Sammy’s Law to reduce speed limits at dozens of priority locations across the city."

But Menin blamed the new mayor for not acting speedily to slow down drivers.

"Under Sammy's Law, the Department of Transportation already has the authority to lower the speed limit in specific locations to 20 miles per hour,” Menin's spokesperson Benjamin Fang said in a statement.

That said, the statement admitted that a Council bill "to lower the citywide speed limit has not yet been introduced."

So whose job is it?

In the fiscal year 2025 budget, the state legislature gave the city the power to lower the speed limit to 20 miles per hour [PDF, see page 41].

Either the City Council or the mayor could act, though the process would be different. The Council could simply pass a bill lowering the posted speed limit on all applicable (i.e. non-state-controlled) city streets in one fell swoop.

And Mayor Mamdani's Department of Transportation could lower the limit in large zones, so long as it notifies the affected community boards and gives them 60 days to review and provide their advisory opinion.

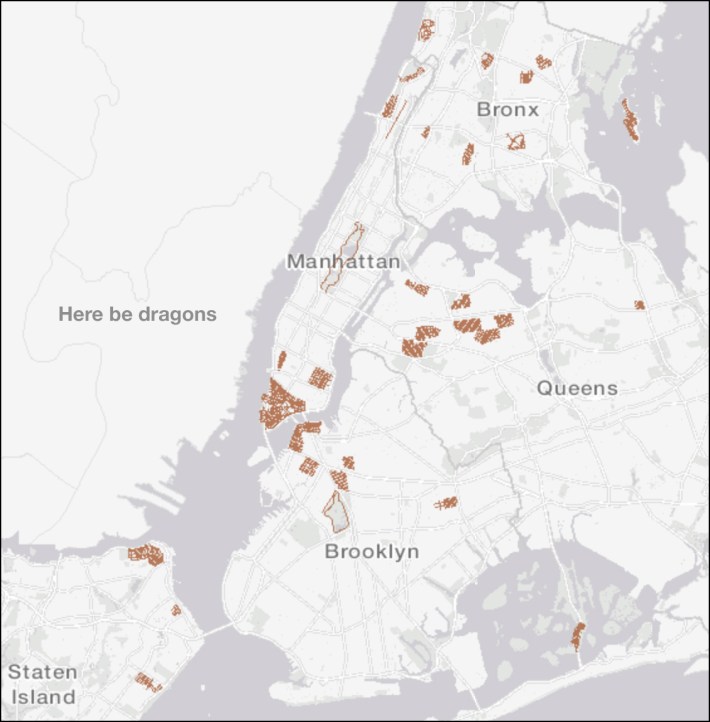

But since the law passed, the DOT has only closed down drivers on short sections of the roadway near schools and created small “neighborhood slow zones,” the zones created with Sammy's Law are south of Canal Street in Manhattan, in Broad Channel, in DUMBO, St. George, and City Island:

The result is a patchwork of speed limits rather than a coherent citywide limit.

Meanwhile, since May 9, 2024, when Gov. Hochul signed Sammy's Law, with then-Mayor Adams looking on, there have been roughly 154,000 reported crashes in the city, or about 240 per day, according to city stats. Those crashes injured 89,750 people, including 16,375 pedestrians and 9,340 cyclists, killing 209 pedestrians and 42 cyclists.

The Department of Transportation has invoked Sammy's Law to reduce the speed limit for cyclists in Central Park from 20 miles per hour to 15. The affected community boards' 60-day advisory review period ends in mid-February, when the new speed limit is expected to take effect if the Mamdani administration intends to carry out then-Mayor Eric Adams's initiative.

Advocates remain stunned that the DOT acted to slow down cyclists in a park before reducing the car speed limits in broad stretches of the city.

“Large vehicles are what are killing people on our roads. We really call on the mayor to implement Sammy's Law on the streets across New York City that we know are dangerous and not focus so much on worrying about people who are getting around on two wheels, the vast majority who are riding safely and are causing very few deaths and injuries on our roads," said Amy Cohen, whose son is the Sammy evoked by the name of the law.

Using the law to lower the speed limit on a bike path was not what Cohen said she had in mind. The Adams administration's implementation of Sammy's Law was not "true to the intent," she added.

“It was very frustrating that [after Sammy’s Law passed] so few streets have been lowered. The city is empowered to go to 20 on the majority of roads in the five boroughs, but only 1.5 percent of eligible streets have gotten the lower speed limit,” said Cohen.

So what do advocates want?

Families for Safe Streets, the group Cohen founded more than a decade ago, wants the mayor to implement the lower limits in community districts that want it, which currently includes Community Board 3 in Manhattan — which already has a slow zone from Canal Street down, but wants to extend it to Houston Street, Community Board 1 in Brooklyn, and Community Board 2 in Queens.

"What we'd really like to see is that Mayor Mamdani starts implementing these safe street zones wherever the community is calling for it," said Families For Safe Streets New York organizer Alexis Sfikas.

The problem with such a strategy, other advocates said, is that progressive areas of the city, where car ownership is lower, will ask the city for lower speed limits, while neighborhoods with heavy car use, might ask the city to raise the speed limit (which it also has the power to do).

In addition, low-income communities tend to lag behind in street redesigns, which are a way to limit speeding without the need to issue tickets. Wider roadways in industrial areas tend to encourage drivers to speed, no matter the posted limit.

But that's no excuse for doing nothing, said another advocate.

“Everybody's at fault. Blame everybody,” said Peter Beadle, a lawyer who represents cyclists who are victims of car crashes. "It’s amazing [that neither the Council nor the mayor has acted] because we have been given a tool that would save lives, have all these external benefits and we are not doing it. It's the art of deflection."

The past could be prologue

The city has been granted the power to lower its speed limit before. In one of their first campaigns, Cohen and Families for Safe Streets got the state legislature in 2014 to allow the city to lower the speed limit to 25 miles per hour from 30. After the bill became law, the then-mayor Bill de Blasio and then-Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito acted quickly to use the new power, with the Council passing a law lowering speed limits uniformly across the city, and de Blasio signing it.

Things could've gone similarly after Gov. Hochul signed Sammy's Law. But Adrienne Adams’s City Council and Mayor Eric Adams’s City Hall did not act in unison. To one former transportation official, the inaction after the passage of Sammy's Law came from the top down.

“What happened was the Adams administration was in power and there was incoherent leadership at DOT as well, which had been beaten down by City Hall, beaten with a stick and brought to heel,” said Jon Orcutt, who was the DOT’s director of policy from 2007 to 2014.

But that need not happen now, added Council Transportation Committee Chair Shaun Abreu. In an interview with Streetsblog last week, the Morningside Heights Democrat said the DOT should be utilizing Sammy's Law to its full capacity, Council law or no Council law.

“DOT now has the authority to act, and I want to see them use that power,” he said. “I believe this is one of the most clear, simple ways the city can prevent crashes before they happen, and there's no reason to stop short. The mayor and the DOT commissioner have the authority to enact it as of right now. They're not applying the fullest extent of that application.”