Put this train on the express track to success.

Gov. Hochul's dream of a western extension of the Second Avenue Subway has a $7.7-billion price tag that calls into question the very logic of building it at all — but advocates and researchers say the train is a good idea that could cost a lot less with some minor alterations.

Last month, Hochul revealed that the MTA plans to pay for the engineering and design work to extend the long-awaited subway west, underneath 125th Street, to Broadway in West Harlem. Under Hochul's timeline, the transit agency would not begin to bore the requisite tunnel before late 2028, which gives the agency some time to tweak the cost.

Planners did not include a 125th Street leg in the original vision for the Second Avenue line, which the MTA planned to run all the way downtown to Hanover Square in the Financial District. But the MTA did take a cursory look at the concept in its 2024 20-Year Needs Assessment, and Hochul's new plan has its origins in a feasibility study that engineering firm AECOM did for the MTA last year

The AECOM study sketched out basic station designs and costs for the effort, and gave the MTA a roadmap to make the project a reality.

But just because the project is feasible, and just because Hochul plans to fund more detailed engineering and design work, doesn't mean that it will happen or that it will happen exactly as the AECOM suggested.

To rein in the costs of what could be the most expensive per-mile subway expansion in history, transit watchers have some ideas.

The basics

The feasibility report answers questions one would need to know before embarking on a very expensive capital project — specifically cost, projected ridership, station size and the kind of soil composition of the land in question. Transit wonks said the study is a good first step.

"Every project should have a document like this," said Eric Goldwyn, a researcher with NYU's Transit Costs Project. "It's readable, it's not too boring. It gives you a decent sense of a couple things that are important, like some of the geological concerns, some of the ideas around station design, and different strategies on tunneling. If you're trying to keep up with a project these are sort of things you need to know about."

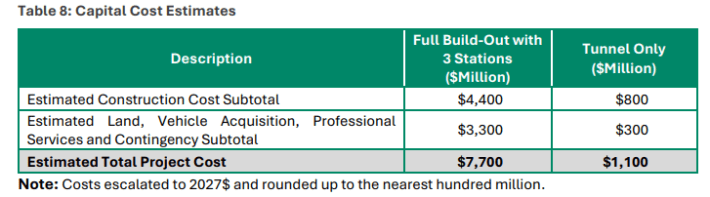

The report also updated previous assumptions about the project to set the stage for its actual construction. For instance, the 2024 Needs Assessment predicted that project would cost $7.5 billion and that 240,000 daily riders would take the crosstown line by 2045. AECOM pegged the cost slightly higher, at $7.7 billion, and ridership at a much lower 163,900 daily riders by 2045 due to the new post-2020 patterns of transit usage.

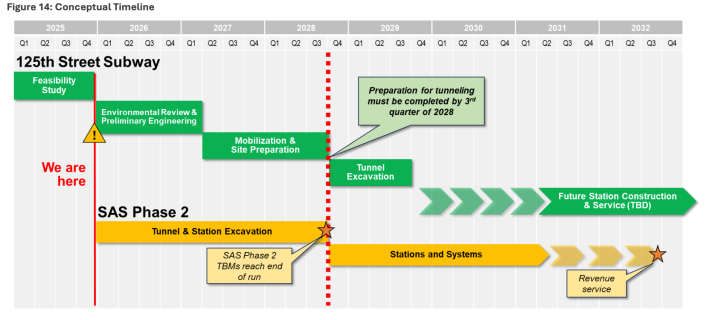

The report also identified the two most realistic ways to actually drill the crosstown tunnel — either drill from west to east from 12th Avenue with a single tunnel boring machine, or use the two machines the MTA is already using to tunnel north up Second Avenue. MTA officials would likely prefer the second choice to save money and time once tunneling up to 125th Street wraps up.

The tunnel boring machines the MTA is using to go north up Second Avenue are already slated to turn west, to bore out a tunnel for the 125th Street and Lexington Avenue station at the northern end of current expansion. Those machines will actually go a bit west of Lexington Avenue, closer to Park Avenue, in order to leave room for tail tracks and other non-service infrastructure, so longtime transportation professionals see inherent value in going all the way west to Broadway.

"The beauty of doing it is that you have a bunch of people working on the predecessor project who can just turn left and continue what they're doing, both consultants and the capital construction team," said Jon Orcutt, a former New York City transportation official and longtime transit advocate. "The fact that they have people already working on an upstream part of the tunnel makes it easy to just keep them on the job and continue the work."

AECOM also studied the option of continuing to tunnel once the current tunneling operation finishes, with or without a plan to build out crosstown stations.

That may be prudent given the long runway for any further expansion. Financing for a full build-out 125th Street crosstown expansion project won't realistically happen until the MTA assembles its 2030-2034 capital plan, sometime in 2029. Funding for the agency's last two capital plans involved all kinds of high-stakes political wrangling, so it is safe to assume that planning and funding for the next one will not just sail through without controversy. With that kind of uncertainty surrounding a full build-out, the AECOM report created what the company called a "tunnel-only" option that would cost $1.1 billion.

It's not a plan without precedent: The MTA built some of the original tunnels for the Second Avenue back in the 1970s abandoning the project due to fiscal crises at the city and state levels. The tunnels existed in a kind of limbo for decades, waiting for someone to cough up the money to fill the void with a train.

If the MTA built the tunnel-only option, AECOM's report said it could save money down the line, since continuing on with the tunnel boring machines would allow the agency to keep the manpower and machines devoted to the current tunnel on the job and any future work on the crosstown could happen without waiting to finish a tunnel.

The MTA would still have to move fast to actually take advantage of the tunnel-only option, the report warned. The tunnel boring machines working on Phase II of the Second Avenue subway will make it to the end of their run by around October 2028, so the agency has until the end of September 2028 to finish the environmental review and preliminary engineering for the tunnel to ensure the machines are ready to head west, the report said.

MTA officials are confident they can meet that deadline. Crucially, officials said that they will not need to do a federal environmental review in order to drill the crosstown tunnel, and instead can rely on the State Environmental Quality Review. The federal government is currently holding Second Avenue subway reimbursements hostage in an attempt to retaliate against New York for not caring much for President Donald Trump. (The first Trump administration rather famously kept congestion pricing in purgatory by refusing to even begin a federally mandated environmental review.)

But can it be cheaper?

The feasibility report gives plenty of runway for outside experts and the MTA to find some ways to chop down the $7.7 billion price tag.

For example, the AECOM study plans for 75 foot-wide stations — significantly wider than the stations in Phase II, which will drive up costs.

"There are things that are concerns. The stations are supposed to be 75-feet wide, and that raises a flag to me. When you look at Phase I stations, they were 58-feet wide, 64-feet wide, so all of a sudden you're now 10 to 15 percent wider, which means your volume will be much greater," he said. "Excavated volume is a big part of what the cost of the stations are, and so anything you're doing to make that volume bigger is going to drive your costs higher."

Goldwyn isn't the only person worried.

Researchers with the Effective Transit Alliance, who previously convinced the MTA to tunnel under All Faiths Cemetery to speed up service on its proposed Interborough Express, said that even the station at 125th Street and Lexington Avenue station — the busiest planned station in Phase II — will not be 75-feet wide, so none of the stations on the crosstown branch need to approach that width. ETA researchers told Streetsblog that keeping the crosstown stations the same size as the Phase I and Phase II stations could save 15 percent on tunneling costs alone.

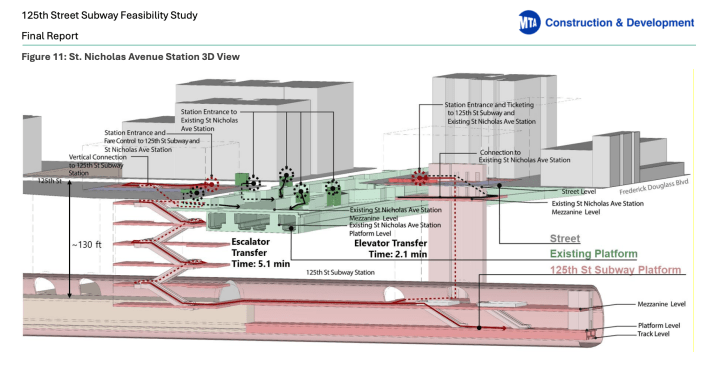

The 125th Street line will be built deep below the surface, according to AECOM, since the stations themselves will have to be 100 feet below existing underground stations on Lenox and St. Nicholas avenues and 100 feet below street level at Broadway.

The stations' placement deep underground means that the MTA won't have to spend money on some traditional problems that make tunneling harder, like utility relocation and vibration impacts, since a subway tunnel that's 130 feet underground won't have as much of an impact on the surface world. But it also makes the tunneling work more expensive, drives up the cost of the station infrastructure and leads to some long transfer times once the new line actually opens.

The AECOM report predicted riders would need more than five minutes to walk from the crosstown platform upstairs to the A/C/B/D platform at St. Nicholas Avenue or the 1 train at Broadway using the planned switchback-style escalators. Marco Chitti, a fellow at NYU's Marron of Urban Management, said officials could solve this issue by installing either high-speed elevators or a single and very long escalator.

"Considering that you need space for landing at each switchback, which is normally quite wide due to the so-called surge space and crowd flow management, you end up with a lot of back-and-forth, which makes the traveling time for riders longer than in a single continuous escalator or just two consecutive ones," said Chitti.

The MTA could explore elevator-only exits and entrances, which he called the most space-efficient way to design stations in a place as deep as the 125th Street line, Chitti said.

Dear North American station designers, this (first two pics) is not how you deal effectively with vertical circulation on a 120-130 ft (35-40 meters) deep station.It's either the Moscow way (long inclined escalators) or the Barcelona/E-M REM way (elevators-only).

— Marco Chitti (@chittimarco.bsky.social) 2026-01-13T22:44:46.597Z

There's also the question of how to mitigate costs that have nothing to do with the physical work of drilling and building. "Soft costs" like professional services (lawyers and other soft-handed types), engineering, land acquisition and federally-mandated contingency fees will cost the MTA an eye-watering $3.3 billion, or 43 percent of the entire project cost, AECOM said.

Khyber Sen, a researcher with the Effective Transit Alliance, said that the MTA has a chance to save on design costs, for instance, when compared to Phase II of the Second Avenue subway, because that project racked up redesign costs in response to complaints that its stations that were entirely too big.

"Phase II design costs were abnormally high because they were redesigned late to save hard costs, but for Second Avenue Subway West, they can be designed correctly from the start," Sen said. "By contrast, Phase II soft costs were 38 percent and Phase I soft costs were only 21 percent. Simply reducing soft cost percentages to Phase I would save $1.7 billion."

It's especially important to keep the total cost of the project down before it starts, because the federal government requires transit building set aside a contingency fund for when the project inevitably runs over budget. A $7.7 billion project like the 125th Street crosstown gets to that price in part because it costs $5.5 billion before the contingency costs. Knocking down the initial cost of the project will lower that contingency fee, experts said.

MTA officials said that the feasibility report won't be the last word on how much the project would cost, and that the more official upcoming design would focus on finding ways to lower the predicted $7.7 billion price tag.

With the feasibility report in hand, now is the time for the MTA to set a narrative and show it can manage to build this expansion for less than the astronomical costs that have been associated with the Second Avenue subway expansion.

Otherwise, researchers say, the project may never actually happen.

"My concern is that if you tell me this project is $8 billion today, I'm going to just say, well, okay, we're not doing it, that just sort of kills the project. Once that number gets out there, it anchors in people's minds," said Goldwyn.