Delivery workers are less likely to run red lights, ride on sidewalks and ride without helmets than their recreational and commuter counterparts — defying claims that they sow street chaos, according to a new observational study of more than 1,700 cyclists.

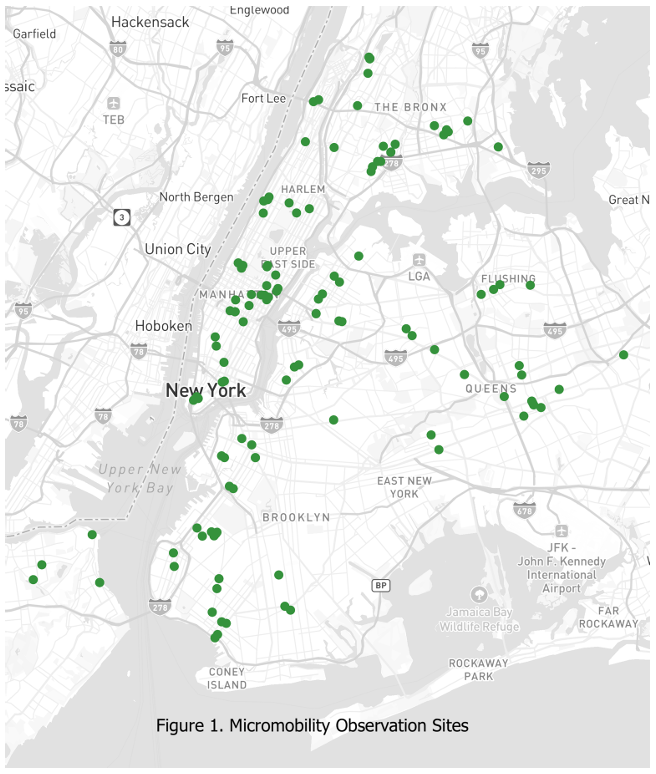

The Hunter College study examined 155 intersections during a three week period in late 2025, when a team of 56 researchers observed individuals using anything that’s not a car to get around: bikes, e-bikes, mopeds and scooters. The researchers looked at the type of vehicles they used and how street design affected their behavior.

"Our results indicated that any implication that delivery workers are less safe than non-commercial riders is misplaced," the study authors concluded.

Fifty-eight percent of recreational and commuter riders disobeyed a red light. By contrast, 55 percent of delivery workers waited entirely for the light to turn green, 27 percent stopped to ensure they were safe and continued, and only 18 percent blew through red lights at speed.

The study acknowledged that treating a red light as a stop sign, known as an "Idaho Stop," is "technically illegal, much as jaywalking was until 2025 [but] is not necessarily unsafe." Delivery workers accounted for approximately 40 percent of observed vehicles.

One of the lead researchers, Prof. Mike Owen Benediktsson, said the workers' behavior followed a certain logic.

“When you think it through, it becomes less surprising,” he said. “It does stand to reason that deliveristas would be more cautious in their riding. They have more at stake, and they're professionals, they're getting a lot more hours engaged in micromobility riding. And I'm sure that they don't relish the idea of getting into an accident and losing their means of making a living.”

Last year, former mayor Eric Adams imposed a 15 mile per hour e-bike speed limit and ordered the NYPD to issue criminal summonses to cyclists. Benediktsson saw the study as a chance to bring more data into the conversation around e-bikes.

“There's been all of this politicized discourse and attention to issues relating to micromobility," he told Streetsblog. "It seemed like an issue where we could do something helpful and shed some light on an aspect of public behavior in the streetscape and an aspect of transportation that's not entirely understood, but that's growing very rapidly."

Advocates said the study revealed what they have known all along. "I'm so glad that this research was done [because] it validates what we have been saying," said Ligia Guallpa, the executive director of Worker's Justice Project, which includes Los Deliveristas Unidos. "Street safety is the number one priority for app delivery workers ... the streets are not safe enough and [there] is a serious lack of infrastructure for workers and for the whole biking community."

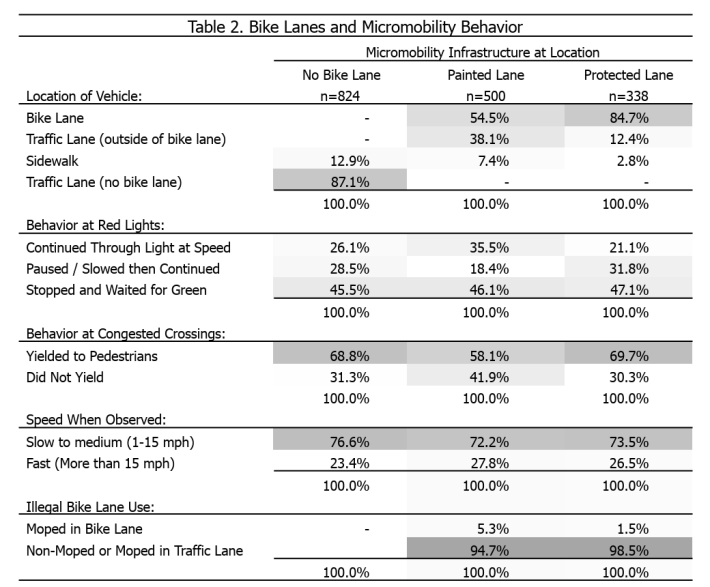

The research supports Guallpa's claims. The Department of Transportation consistently says that protected bike infrastructure increases safety for all road users, but the Hunter study found that they also increase the feeling of safety and decrease recklessness — even if that recklessness would not have resulted in a recorded crash.

The study also found that the lack of protected bike infrastructure correlates with more cyclists riding on the sidewalk. Just 2.8 percent of riders take the sidewalk in the presence of a protected lane, but that rises to 12.9 percent of riders when no infrastructure exists. This is "strong evidence" that riders use sidewalks when they feel unsafe and unprotected in the roadway.

There are "multiple payoffs of protected bike lanes," Benediktsson said. "Cyclists and e-bike riders are safer in those protected lanes, in real terms. But there's also the psychological effect of feeling safer. Beyond that, the feeling of having a formal space in the roadway that belongs to you, is what may explain our finding that people are more law-abiding generally when they're in protected lanes."

The study is the second recent attempt at understanding who uses the city's bike infrastructure. Last January, an MIT planning student revealed that all “motorized micromobility vehicles” — basically anything with a motor – made up 74 percent of vehicles in protected bike lanes at five locations. The DOT counts bikes in popular commuter locations and bridge crossings, but their sensors don't record the types of vehicles being used.

Guallpa wants to see the city embrace electric micromobility for workers and other New Yorkers who can benefit from the affordable and environmentally friendly technology.

"We need more bike lanes, we need better roads and conditions, bike parking, delivery zones," she said. "New York city needs to embrace the fact that e-bikes are a new mode of transportation."

This story has been updated to reflect the correct timeline of the Hunter study and the language its authors used to describe non-delivery cyclists. We thank Charles Komanoff for bringing these errors to our attention.