Cyclists should follow the same rules as everyone else, right? In fact, history shows that the rules of the road we have today were written by and for drivers. Cyclists are different than drivers, so some of the rules for them must be different, too.

Most state and local governments make exceptions to our car-centric traffic rules. In New York City, for example, a 2019 law permits cyclists to proceed with the “walk” signal, even on a red light. The law recognizes that in traffic rules, one size does not fit all.

Recently, however, cyclists following this law have been cited for red-light violations. And as Streetsblog has reported, NYPD has been “issuing criminal summonses to cyclists for a wide range of low-level traffic infractions.”

A minor traffic infraction may be a street user’s best attempt to find a safe compromise between abstract rules and real situations. Because the rules of the road were written primarily for drivers, such improvisations are often practical necessities for people who are not in vehicles.

People on foot, on bikes and other micromobility modes, and in motor vehicles need different rules to suit their different needs. In the U.S., however, we tend to forget about anyone who is not in a motor vehicle. If you’re not in a vehicle, you’re an oddity who must find a way to conform with the favored class of street user.

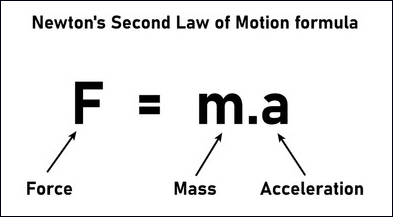

The bias can prevent us from seeing traffic impartially, and from recognizing elementary facts. Traffic laws follow from laws of nature, the ones Newton defined centuries ago. Force equals mass times acceleration; for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.

In baseball, a catcher needs a catcher’s mitt. For Newtonian reasons, a rule requiring catchers to wear a mitt makes sense. But if someone tosses you an egg, you should ignore the rule for fast-pitched baseballs. If they tell you “egg catchers are required to follow the same laws as baseball catchers,” you should disagree.

Before cars and trucks, we didn’t need rules to protect people from them. It was cyclists, not drivers, who first prodded cities to introduce traffic safety rules. As cycling surged in the 1890s, authorities had to warn cyclists to yield to pedestrians – a rule that still applies in New York City today, wherever pedestrians have the right of way.

In 1897, for example, the Board of Aldermen for New York City (then just Manhattan Island and the Bronx) regulated cycling. Cyclists had to obey an 8 mph speed limit, keep off the sidewalk, equip their mounts with “an alarm bell or gong,” and shine a light at night. The reason, again, was Newtonian. Cyclists’ speed can make them dangerous to pedestrians – not the other way round.

The rules of the road soon changed; today's hardware of traffic control – traffic lights, traffic islands, stop signs and so on – originated primarily to constrain drivers. Such equipment was introduced as deaths and serious injuries surged. But the software – the rules – have been rewritten many times, often to the disadvantage of anyone not in a car.

It’s a useful oversimplification: As cyclists are to pedestrians, motorists are to cyclists. Enormous momentum makes the driver a hazard to people on bikes – not the other way round. This is one reason why we need different rules.

In the early days of driving, cities installed posts to prevent unsafe left turns.

The first generation of traffic rules tended to restrict drivers so as to protect the non-driving majority. To turn left, for example, a driver first had to pass the center of the intersection. A post planted at the centerpoint enforced the rule. The rule protected pedestrians by slowing drivers down and preventing them from approaching walkers from behind.

But as automobile interest groups organized, they rewrote the basic traffic rules. The new rules tended to serve drivers’ convenience at the expense of other street users. That’s how the old left-turn rule was lost. By turning on a large radius, drivers could maintain speed – and deter pedestrians from exercising their legal rights in the crosswalk. The change was a big win for drivers, but it gave other street users reason to question why they should conform to rules that no longer protected them.

In the 1970s, the proliferation of right-turn-on-red rules for drivers was proof, if anyone still needed it, that traffic rules are not really for everyone. They put drivers’ interests first.

Cyclists stopped at a red light tend to keep to the right of the street, so that drivers going straight may proceed. But if a driver passes a cyclist and then executes a right turn, the cyclist – no longer in the driver’s field of vision – may be in mortal danger. It’s one of the most common causes of injury or death to people on bikes.

Right turns on red compound this danger. They are prohibited in New York City, but for a cyclist, even a driver making a right turn on a green light can be a threat. A cyclist who is just to the right of such a driver is in danger.

To protect pedestrians, and to earn their respect for the rules, many cities have introduced a “leading pedestrian signal.” The pedestrian gets a “walk” signal before a driver facing same way gets a green light. The rule protects pedestrians by giving them a chance to cross before turning drivers invade the crosswalk.

The leading walk signal is an excellent way to protect both pedestrians and cyclists. It can prevent the danger from right-turning motorists. It is also more convenient for the driver. If stopped cyclists gather with drivers at a red light, at the change to green the driver has to take exceptional care. But if the cyclists can pedal off before drivers get the green, they simplify drivers’ situation.

When authorities insist that cyclists and drivers follow the same rules, even when the rules favor drivers, cyclists are less safe. But driving is less convenient, too. Such conditions deter the more cautious cyclists. The ones who keep biking are the more assertive and improvisational kind. They are the bikers who take the lane and mix with motor vehicles. At a red light, a cyclist who can’t cross on a leading walk signal would be wise to wait in the center of the lane directly in front of waiting drivers, to avert the danger of right-turning motor vehicles. Many cyclists find this position stressful – and many drivers find it annoying.

But when cyclists can cross with pedestrians, drivers win, too.

After generations of traffic engineering intended to make driving easier – at a cost to everyone else – we can’t expect all street users to follow the same rules. Attractive dogmas such as “the rules are there for everybody” don’t stand up to scrutiny. History proves that the rules are like a football that opposing teams vie to possess. History also shows us that when one team writes the rules, others learn to improvise, violating rules that do not protect them or give them a reasonable degree of convenience.

But the corollary reveals the way forward: When rules recognize reality, suiting the distinct needs of categorically different users, everybody wins.

Streetsblog has been covering NYPD Commissioner Tisch's decision to turn traditional traffic tickets into criminal summonses like no one else in town. Here's a full list of our coverage over the past two weeks, in case you have missed something or need a reminder that when there's a big story on the livable streets beat, turn to Streetsblog:

- May 2: "Policy Change: NYPD Will Write Criminal Summonses, Not Traffic Tickets, for Cyclists."

- May 5: "NYPD’s Red Light Criminalization Marks ‘Obscene’ Escalation: Advocates."

- May 6: "As NYPD’s Criminal Crackdown on Cyclists Expands, It Grows More Absurd: Victims."

- May 7: "Komanoff: Tsk, Tsk, Tisch — Criminal Summonses for Cyclists Will Backfire."

- May 9: "NYPD’s Push To Criminalize Cycling Spells Trouble For Immigrant Workers."

- May 12: "Cyclist Launches Class Action Suit For Bogus NYPD Red Light Tickets."

- May 14: "NYPD Admits Bike Crackdown Based on ‘Community’ Vibes, Not Data."

- May 15: "Tisch Rap: NYPD Criminal E-bike Summonses Surge 4,000 Percent."

- May 15: "Quiet Desperation: NYPD’s Tisch Didn’t Tell DOT About Her Crackdown on Cycling."

- May 16: "‘All in the Family’: NYPD Commissioner and Power-Broker Mom Are Both Crusading Against E-Bikes."