Fare-free buses would juice bus speeds and ridership while also bringing economic benefits to bus riders themselves, according to a new study of the policy by a renowned transportation economist.

Charles Komanoff, whose traffic models evaluated and proved the feasibility and merits of congestion pricing, used his same modeling prowess to determine what would happen if the MTA moved to a fully free bus system. Per Komanoff's research, buses would move faster and complete their routes more quickly without fares, and the lack of fares would also attract almost 170 million more riders to the bus system.

The key to the increased bus speeds is that by doing away with fares, you reduce the dwell time — the amount of time it takes to get people onto the bus — at each stop. At present, local buses only allow riders to get on using the front door, which means that a bus driver has to wait for every passenger to pay one at a time. Transit advocates have for years pressed the MTA to cut dwell times by allowing riders to use the back door, a policy known as "all-door boarding" that is used in other cities around the world.

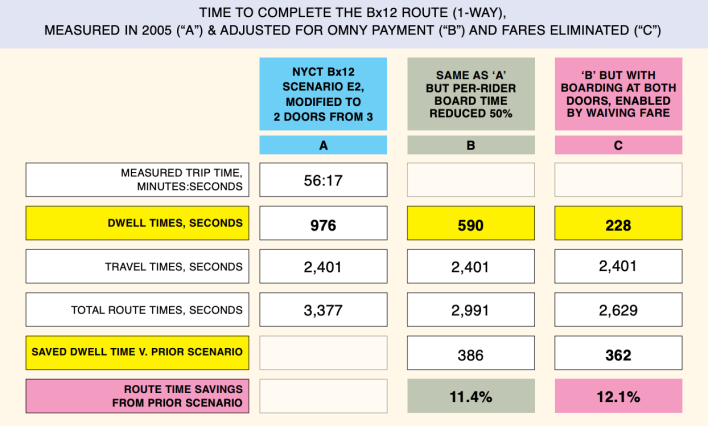

The MTA is well aware of the benefits of all-door boarding, as a 2005 internal count of the Bx12 route found that "that the combination of all-door boarding and eliminating fare payment would cut bus dwell times on the Bx12 by a whopping 78 percent, shrinking overall trip durations by 22 percent."

But that did not reflect that bus boarding is 50 percent faster in 2025 than 2005, thanks to the introduction of the ability to tap to pay using OMNY. As a result, using the MTA's data, Komanoff found that removing fare payment from the equation would reduce the dwell time on that route by 362 seconds — a 12-percent reduction in trip times.

So Komanoff extrapolated that route across the entire system, and determined that if buses were 12 percent faster, that would boost bus ridership by 7.2 percent on its own. Cutting out fares boosts ridership by an additional 15.6 percent, Komanoff wrote, for a total net ridership gain of almost 23 percent.

In terms of raw numbers, that would mean increasing annual bus ridership by 169 million riders per year, from 743 million annual riders as of 2024 to 912 million in a fare-free system. Two-thirds of those additional 169 million riders would be the result of the elimination of fares, and one-third would come from sped-up trips.

Introducing fare-free bus service would mean that New York State or City would need to replace a little over $600 million per year in fares that the MTA gets from bus ridership at the moment. But Komanoff argues that the benefits of free bus service would pay for themselves.

"Each dollar of city government support would produce more than two dollars worth of benefits for residents, primarily by removing the burden of fare payments while providing faster and more reliable bus service," he wrote.

Komanoff's modeling has always placed a monetary value on the impact of traffic and the time people save by not wasting their lives in gridlock. He brought that analysis to the potential for free buses as well, and found that the bus speed increases brought about by dwell time reductions would save bus riders collectively $670 million per year. Motorists would themselves save about $55 million thanks to slightly faster trips and there would also be $43 million in citywide annual benefits thanks to cleaner air, fewer crashes and an uptick in cycling and walking, all of which would be the result of slightly fewer vehicle trips in the city.

One caveat

The one interesting wrinkle in the study is that fare-free buses wouldn't lead to a huge reduction in vehicle trips or vehicle miles traveled in the city. Komanoff found that even with all those 169 million new bus riders, there would only be a reduction of 16 million fewer private car or for-hire vehicle trips per year and 38 million fewer VMT annually, a little more than 1 percent. This smaller mode shift is due to the fact that so many people in New York City already rely on public transportation.

"This 10- or 11-fold ratio between additional bus trips and eliminated car trips

reflects transit’s dominance in New York transportation. Among the people who will ride buses more if they are free, relatively few will be foregoing cars or cabs," Komanoff wrote.

But other than the surprising lack of a huge mode shift, Komanoff said free buses remain a good idea because the faster bus speeds would make service so much better.

"Everything else I found pretty much fit my expectations: making bus trips free is good transportation policy," he told Streetsblog. "I've liked the idea ever since 2007-08 when I saw 'dwell time' treated quantitatively. Bus boarding is such an impediment to better bus service."

The report will only add to the ongoing debate over free bus service in New York City. While the MTA has been cool to the idea, Assembly Member Zohran Mamdani and state Sen. Michael Gianaris, both of Queens managed to get the agency to do a free bus pilot between 2023 and 2024 as part of an overall MTA budget rescue package in 2023.

Mamdani has made free bus service a big piece of his mayoral campaign this year, and the idea seems to resonate with voters: one recent poll from Data for Progress found 72 percent of city voters and majorities of Democrats, Republicans and independents approved of the idea of the city paying for free bus service.