Getting people onto trains has never been more important.

It’s simple physics. A thousand-foot commuter train can hold 1,000 people; a string of cars 1,000-feet long would hold no more than 100 people, even if each car was smaller than a Mini Cooper. Getting people back on trains and onto transit is essential to bringing our cities back to full health post-pandemic and building beyond into the future. Congestion pricing proves that reducing traffic improves quality of life and bolsters local businesses. Speeding up and expanding service is proven to grow ridership on existing routes and induce mode-change, fueling a virtuous cycle that boosts transit and our cities.

In London, the launch of the Elizabeth Line led to a jump in return to office rates, fueling the city’s recovery. Paris has seen similar success and is mounting a massive expansion of its metro, the Grand Paris Express project, and of its commuter rail system, the RER.

The infrastructure we inherited, had we consistently upgraded and funded it like the Europeans have done with theirs, would allow many mainline U.S. cities to deliver passenger rail service that rivals what’s found abroad. But our agencies don’t receive the funding to provide it. By necessity, starved agencies focus on survival and have little capability to present a forward-looking case for what properly funded transit can provide. This means politicians face little pressure to do more than ensure the current system doesn’t collapse. Stasis ensues.

Momentum — released Wednesday by the Marron Institute at New York University — is an exhaustive 156-page effort to examine the causes of this logjam and to propose a dramatic set of reforms to break it wide open. It illustrates what our current routes and systems would be capable of if they are modernized around a shared common standard. It fleshes out what that standard should entail: electrification, level-boarding, fast-accelerating trains. Adoption of this high-throughput infrastructure framework would allow commuter and intercity rail services to deliver time savings on existing routes that are so substantial that commuting or traveling by train would become markedly quicker than driving and competitive with flying.

Widespread implementation of this framework would allow passenger rail services to finally meet the Congressionally mandated goal of modern, fast and efficient service that provides a viable alternative to the automobile and air travel.

How to do it

This Momentum framework speeds travel with a four-pronged attack on "dead time." That’s the cumulative time penalty incurred at each stop for deceleration into the station, boarding and disembarking, and then re-accelerating back up to speed. Modeling shows that full implementation can shorten commutes by as much as 29 percent and slash an hour or more off of many inter-city services. In short, the framework will allow American rail planners to deliver the aggregate benefits of high-speed rail at lower costs, while minimizing the regulatory and political risks.

The first half of the program — a focus on stations — calls for the construction of universal high-level platforms along the improved routes. This will speed boarding and disembarking by allowing passengers to easily walk on and off trains — a concept known as level-boarding — instead of requiring that they use stairs or lifts. Level boarding also improves accessibility by making it easier for the disabled, the elderly and those with young children to board.

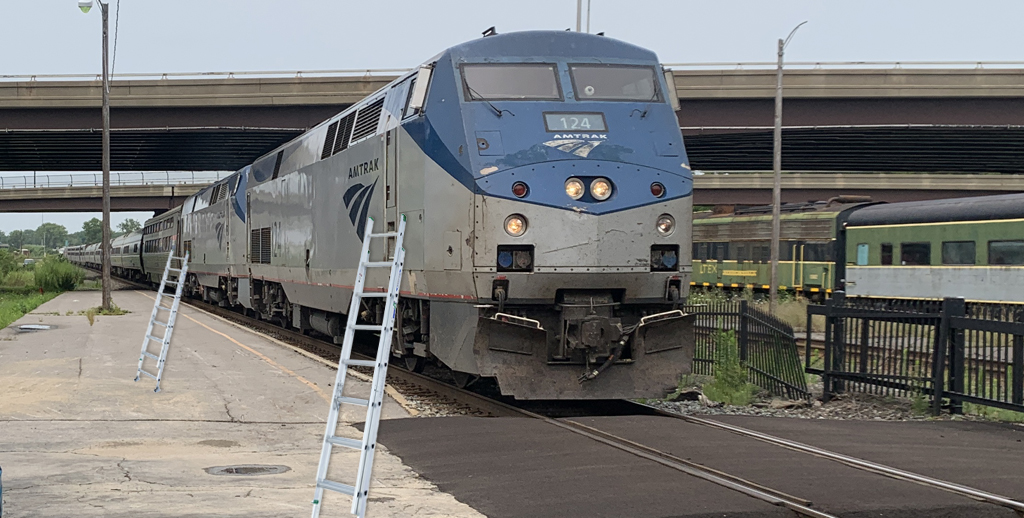

Second, universal high-level platforms allow rail operators to switch to passenger rail car designs with much wider doors, which further speeds boarding and improves accessibility for passengers in wheelchairs. Level boarding combined with the optimized passenger car designs saves 30 to 60 seconds per stop for commuter services and two minutes-plus per stop for Amtrak’s intercity services.

The second half of the program focuses on the acceleration and deceleration performance of trainsets. Diesel trains don't get up to speed quickly because they're heavy and the source of traction is limited to the locomotive at the front. Momentum tackles this with a two-part solution: electrifying routes and the adoption of electrical multiple unit trains — essentially, all-wheel drive for trains — to dramatically improve acceleration.

It can take 120 to 180 seconds for a diesel locomotive-hauled passenger train to get up to 80 mph; but an electric multiple power unit train can do it in 60 seconds. That’s another 60 to 120 seconds in savings per stop. And with electric power units, the subway-style distributed traction system means there is no time penalty for running longer trains, a substantial benefit when compared to locomotives.

The biggest beneficiaries of the Momentum framework are routes with several stops. A hypothetical service with 12 stops at stations with low platforms operated by a diesel locomotive would lose 56 minutes to dwells, acceleration and deceleration — cumulatively, dead time. The high-throughput framework would slash the dead time down to 31 minutes, a savings of 25 minutes.

The most likely candidates for these improvements are the lines that are substantially or completely owned by the public. Additionally, we believe that government agencies and lawmakers can unlock tremendous value for the public by purchasing underutilized freight railroad lines or rights-of-way and repurposing them for high-throughput passenger rail service. This makes commuter railroads an obvious candidate.

The MBTA’s service between Providence and Boston is operated by diesel locomotives serving stations with a mix of low- and high-level platforms. This configuration means the trip takes 73 minutes, which is even with driving. Momentum slashes that to 54 minutes. This flips the value proposition between transit and cars by making the train 25 percent faster. It also simplifies scheduling on the corridor by bringing MBTA service speeds closer to Amtrak’s inter-city services, potentially allowing those to go faster, too.

Our research shows the high-throughput framework would provide a step-change improvement to intercity services, too. Electrification and full modernization would slash trip times between New York City and Albany down to one hour and 54 minutes to two hours and five minutes, which is a half-hour quicker than current service. Or take the route between Chicago and Detroit, large portions of which are publicly owned. Amtrak #352 travels between the two cities in five hours and 25 minutes. Momentum, combined with long-planned improvements to the Chicago approach, would slash trip times to three ours and 50 minutes. That’s an hour faster than driving and roughly the same as flying, when counting time spent at the airport.

Momentum aims to fill a substantial gap in American rail planning, which has been largely confined to two different service types off the Northeast Corridor: First, low-frequency diesel service that operates on existing rights-of-way with theoretical top speeds of between 80 and 110 mph, speeds rarely reached because of diesel’s poor performance. Second, greenfield high-speed rail projects, which boast top speeds of up to 220 mph. However, high-speed rail projects struggle to get off the ground because of extremely high price tags, intense regulatory reviews, eminent domain battles and substantial opposition from communities along the routes.

Momentum reduces the footprint of the projects by focusing on modernizing existing rights of way. This avoids regulatory burdens and legal risks associated with entirely new routes. Second, upgrading existing routes means that all communities that currently receive service will benefit, changing the winners-losers dynamic that has fueled opposition to high-speed rail proposals. Third, it is a fraction of the cost of California High-Speed Rail’s $232-million-per-mile average cost. The most intensive application of the framework is projected to cost $72-$95 million per mile, which is less than half the per-mile cost of California High Speed rail. Upgrading routes that are already grade separated or run through rural areas would be far cheaper, approximately $28 to 41 million per mile. Fourth, it lays in the infrastructure for future upgrades to true high-speed rail service.

Momentum is most applicable in parts of the country with substantial amounts of publicly owned or underutilized privately owned tracks, predominately the Northeast and Midwest. Beyond available infrastructure, both regions are home to established commuter and intercity operations that have constituencies and political support, key ingredients to building support for funding.

We think of it as a standards manual for rail electrification and modernization. We aim to empower riders, advocates, planners and politicians seeking to improve rail service and invigorate our communities. Our goal is simple: Momentum for transit.