It's great news that Amtrak has started construction on a pair of new tunnels under the Hudson River, but where the additional trains will end up is still not completely clear. The governors of New York, New Jersey and Connecticut must forge a unified vision of regional rail in the New York metropolitan area to find the right answer.

Amtrak's recent report, “Doubling Hudson River Capacity,” left many rail transportation advocates disillusioned. Rather than providing a roadmap for improved operations including, through-running at Penn Station, the report underscored a critical issue: Without decisive leadership that transcends the interests of the three railroads (soon to be four) operating at Penn, progress on a true seamless vision for commuter rail in the New York, New Jersey and Connecticut metropolitan region will continue to be an elusive goal — regardless of the additional capacity provided by the Gateway project.

Advocates had hoped this report would yield a forward-thinking assessment of future possibilities. Instead, the report acknowledged the urgent need for a long-term vision and strong leadership — things Amtrak is not positioned to provide.

In its report, Amtrak stated that, "Cross-regional rail in the New York metropolitan area requires investment across the rail network where the service would be provided. It requires an integrated long-range plan for the entire regional rail network, which does not exist at present. There is no single entity responsible for rail transportation planning, investment and operations at the scale of the multi-state region."

The last sentence makes it clear — nobody is in charge of regional rail goals. So while Penn Station physically can manage through-routing, a lack of regional governance stymies any progress towards that happening and potentially inflates costs for accommodating any increased service at Penn Station.

A leadership void for a new transportation problem is what led to the creation of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey by Congress in 1921. The Port Authority’s mission was, and still is, to plan, build and operate key infrastructure like the Holland and Lincoln Tunnels, the George Washington Bridge and our local airports — infrastructure operated between the two states.

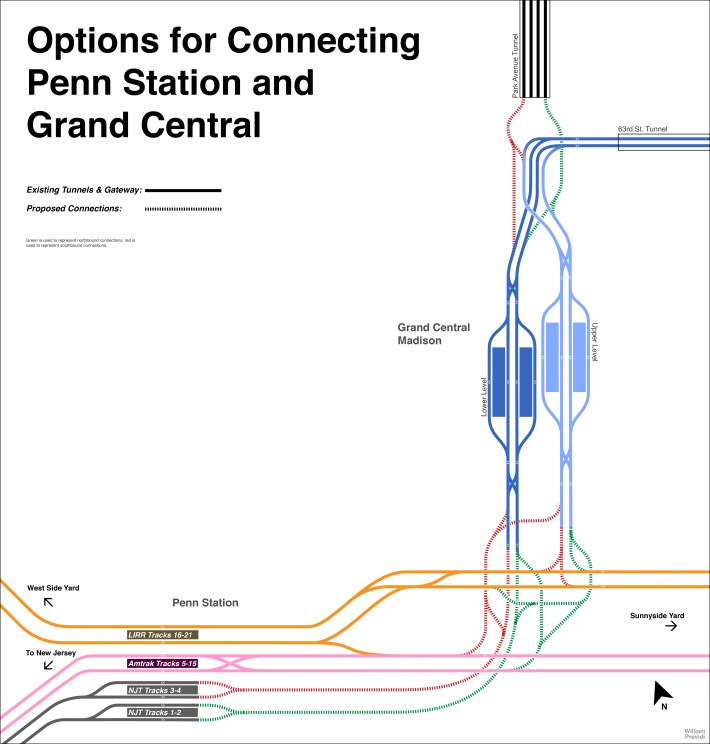

By dismissing discussion of any new ideas for how to operate Penn Station, however, Amtrak's report sidestepped discussions of potential through-routing options, focusing solely on the requirements to serve NJ Transit and the LIRR in their current operating configuration. While the report noted that the current plan does not preclude future options, such as a connection with Grand Central, the omission was glaring.

The report proposed an extravagant addition of 10 new terminal platform tracks at an estimated cost of $18 billion — more than the cost of constructing the Gateway tunnels. This could necessitate the use of eminent domain to demolish nearly two blocks of Manhattan real estate at an extremely high cost.

By limiting its review of operating alternatives to current jurisdictional control in the absence of a regional plan, Amtrak leaves the public unable to effectively assess if the $18 billion cost Amtrak has proposed against all other future options. Amtrak’s report also left hanging the question about how through-routing could be a more cost-effective solution. But as its stated, nobody is in a position to ask if building a connection to Grand Central could reduce the number of platform tracks or the need to tear down two blocks of Manhattan south of Penn Station is the best investment.

Globally, many metropolitan areas, like London, Paris and Munich, have repurposed older commuter rail lines to sew together a broader vision of regional rail service and seen dramatic increases in ridership. So we are faced with a reality that there is nobody in charge of a future vision with the ability to conduct just such a review.

If we want a better outcome, then before Amtrak commits $18 billion to expand Penn Station, the governors of New York, New Jersey and Connecticut should create a new entity similar to the Port Authority, this time for regional rail and its first missions must be conduct a comprehensive study evaluating all through-routing options, including a link to Grand Central.

This review must be guided by strong leadership capable of conducting an unbiased technical assessment that presents the public and elected officials with phased options that can be implemented over 20, 30 or even 50 years. Doing so will in the long run save capital dollars and increase rail ridership and give people options to driving from one end of the region to the other. A previous NJ Transit report indicated we can reduce the impact of doubling capacity under the Hudson on Penn Station with a link to Grand Central.

A 2003 report, "Access to the Region’s Core," sponsored by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, New Jersey Transit, and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey explored how a link to Grand Central could benefit NJ Transit customers, estimating that 36 percent of NJ Transit riders would utilize Grand Central if such a link were available.

Given that there were approximately 200,000 average weekday travelers under the Hudson River pre-COVID — and assuming the goal is to double that capacity to 400,000 daily — integrating a link to Grand Central could divert 144,000 of the 400,000 daily NJ Transit riders from Penn Station. This would unclog Penn, reduce subway crowding, and significantly lower the projected increase in NJ Transit passengers coming from the new Gateway tunnels to Penn from 200,000 a day to only 56,000. Factor in the shift of some LIRR riders to the new Grand Central link and the net growth at Penn could be zero.

To make the highest and best use of both existing rail infrastructure in the New York metropolitan region with the investment in Gateway, there must be a more holistic view of all three commuter rail systems' current operations throughout the region and a willingness to reimagine their future as one system. In 1953, New York City’s subway system was consolidated from three separate entities—the IRT, BMT, and IND—into the unified system we know today.

The investment in doubling capacity under the Hudson River could spark a multi-year transformation of these three huge but distinctly separate operations into a seamless, truly regional vision for commuter rail in the New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut metropolitan region. The time is ripe to reexamine all possible options before it's too late. Governors, the next step is in your hands.