The richer they are, the more they want parking.

New Yorkers who earn more than $150,000 per year are significantly less likely than their middle- and working-class neighbors to support an Adams administration bid to stop requiring developers to build costly parking at new projects, according to a new poll.

The poll by Slingshot Strategies and the pro-housing group Open New York showed overwhelming support for Mayor Adams's "City of Yes for Housing Opportuny" zoning reform, which are in the midst of two days of hearings at the City Council.

Overall, 81 percent of city registered voters support "a zoning reform proposal [that] would address the housing shortage by making it possible to build a little more housing in every neighborhood," the poll found.

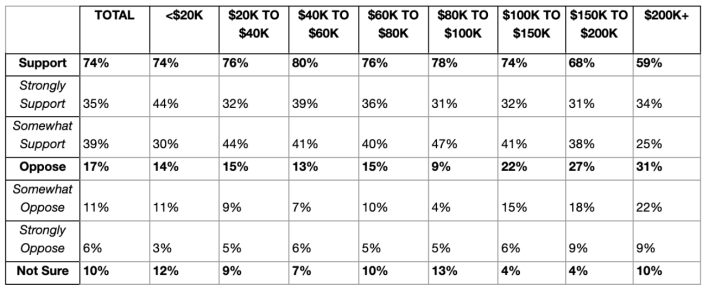

And on the specific question of eliminating mandatory parking, 74 percent expressed support. It has been widely shown that the parking requirement drives up the cost of housing development.

"The polling is pretty decisive that overwhelming majorities of New Yorkers feel that parking mandates are a perfectly reasonable sacrifice at the altar of brining down housing costs," Slingshot pollster Evan Roth Smith told Streetsblog.

Support dropped to a smaller majority of 68 percent among voters who make between $150,000 and $200,000 per year, and to 59 percent among those making over $200,000, the poll found. In other income brackets, the amount of support for eliminating the decades-old parking minimums ranged from 74 to 80 percent.

"The staunchest opponents of any element of 'City of Yes' are more likely to be older, whiter, higher income and own their homes — and less likely to have kids in school, which helps explain why their voices have been so loud," Smith said.

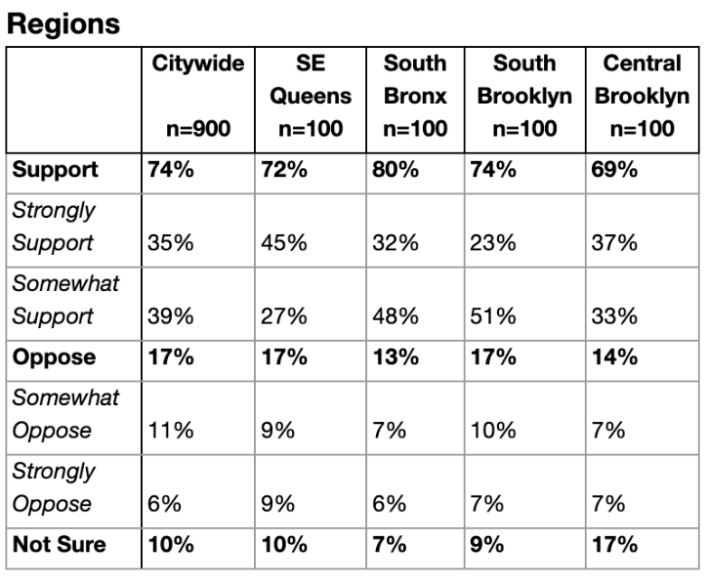

Just 17 percent of city voters opposed the proposal, the poll found. Separated out by parts of the city, opposition to eliminating parking mandates sits at 13 percent in the South Bronx, 14 percent in Central Brooklyn and 17 percent in both south Brooklyn and southeastern Queens.

Politico New York first reported the top-line results of the survey.

Adams's bid to gut the city's 63-year-old parking mandates stands out as one of the most impactful, and controversial, of the City of Yes proposals. A parking spots cost $67,500 on average to build, according to the Department of City Planning. That leads developers to build less housing and charge more rent. City of Yes would not prohibit developers from building parking — as some members of the Council apparently believe based on Monday's hearing — but merely give them the choice not to do so when it's unnecessary or unwanted by would-be renters or buyers.

Reporters from the New York Times highlighted the absurdity of the city's existing parking minimums in an analysis on Monday that used a new building less than two blocks from the subway in Crown Heights as an example.

Despite the proximity of both the subway and the MTA's B44 Select Bus Service route, the 328-unit building at 975 Nostrand Ave. will have a whopping 193 subterranean parking spots. That will encourage more new residents to own cars and drive, exacerbating congestion in the area.

"We know that these outdated mandates for parking drive up the per unit cost of affordable housing," said Open New York Executive Director Annemarie Gray. "If parking is needed, it'll still get built. These are really sensible changes that cities around the country have done. When you have these outdated mandates, it really makes it harder to lower housing costs for everybody."

City officials have slowly clawed back the 1961 rules in recent decades, beginning in 1982 when the Koch administration eliminated car storage requirements for Manhattan below 96th Street on the East Side and below 110th Street on the West Side. Former Mayor Bill de Blasio eliminated them from fully affordable housing developments in transit-rich areas in 2016.

Local opponents of new development often insist on parking construction because they think new residents will otherwise compete with them for precious on-street spots. In reality, most residents do not choose to have a car if transit is nearby and they don't have somewhere to store it.

Some elected officials have tried to have it both ways — acknowledging the costly burden of existing requirements while insisting certain neighborhoods don't have sufficient transit to make do without off-street car storage.

But City Council members drowning in the concerns of constituents opposed to the proposed zoning reforms should realize that those voices don't reflect the majority of actual voters, Smith said.

"What's interesting about the geographic breakdown is that it's not interesting. The idea that there's specific parts of the city where people will riot in the streets if City of Yes would pass [is] a myth," he told Streetsblog. "It's just not true that New Yorkers are radically different in terms of their desire for some meaningful action from the city in addressing its housing crisis."