More than five decades have passed since planners baked mandatory parking requirements into NYC's zoning code. In those 56 years, the public consensus has shifted dramatically. Today, it's widely acknowledged that transit and walkability, not car capacity, underpin the health of the city; that climate change poses an imperative to reduce driving; and that New York is in the grips of an affordability crisis that demands an all-out effort to make housing more abundant and accessible.

Parking mandates cut against all of these objectives, but they have barely changed since 1961.

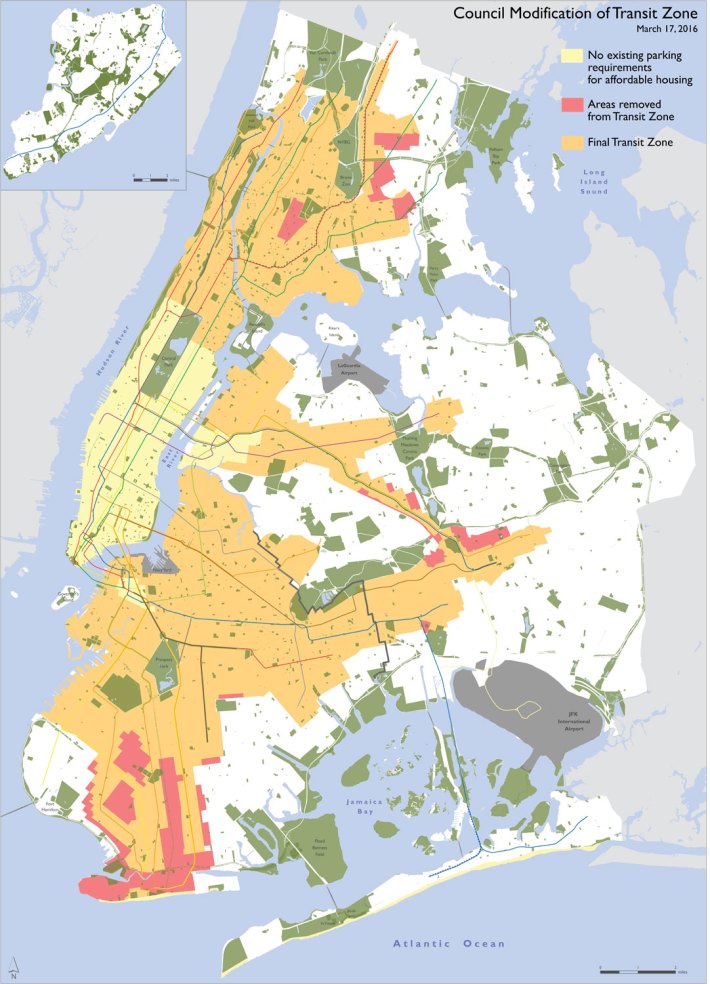

Last year, the de Blasio administration did enact reforms that reduced parking requirements for subsidized housing within walking distance of transit stations. It was a significant step because it showed, politically, that parking mandates can be changed. For most development, however, parking requirements remain in place except in the Manhattan core and parts of Long Island City.

Against their better judgment, developers must build an outrageous number of parking spots -- which often sit empty. That raises housing prices both by limiting how many total units can be built and by constraining developers' ability to subsidize below-market units.

Fortunately, there's already a substantial appetite to expand on last year's parking reforms. At a forum yesterday held by NYU, Transportation Alternatives, and the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, advocates, developers, and policymakers discussed the problems with the status quo and started to outline next steps.

Every day that parking requirements remain in the zoning code takes New York in a less affordable, more car-centric direction. Take Blesso Properties' 545 Broadway project in Williamsburg. Built around an existing bank building, the development will add a 27-story mixed-used tower with 226 rental units, of which 30 percent will be below market-rate.

But Blesso has to build one parking space for every two market-rate units, one for every two below-market units set aside for households making more than 80 percent of the area median income, and one for every 1,000 square feet of commercial space. The surface parking and garage will take up the building’s front yard, basement cellar, and parts of the first and second floors. That’s despite the fact that the location is transit-accessible to Manhattan below 110th Street, Long Island City, and downtown Brooklyn in 20 minutes or less.

Overall, Blesso estimates that it's eating a $12.1 million loss by building parking instead of retail on its first and second floors. New York City's affordable housing strategy relies on private developers to subsidize rents in some units. So if not for parking requirements, Blesso could have put millions toward building more apartments or lowering rents instead.

"If it weren’t for this parking requirement, we wouldn’t do any parking, most likely," said Blesso President David Kessler. "There isn’t the need for parking in this location."

New York's on-street parking policies -- which allow anyone to park on most streets for free -- make the politics of off-street parking reform challenging. Many New Yorkers see off-street parking requirements as a safeguard against competition for free on-street spaces. Perversely, the city's reluctance to charge for parking -- which most households never use, because they don't own cars -- is making housing -- something that everyone needs -- more expensive.

"Basically, New York City has for parking what we wish we had for housing," said Fred Harris, a former NYCHA executive who now serves as managing director of the real estate firm Jonathan Rose Companies. Free or low-cost parking is available for the masses, while a small segment of wealthier residents pay for luxurious off-street spots.

To further reduce parking mandates, Harris thinks the city needs to package parking reform in a way that "makes life better" for people who drive, perhaps by tying it to an on-street parking permit system. "A political solution really has to address the people who are out there using the parking, and somehow make it a little better for them," he said.

Commercial parking requirements, which are less politically touchy than parking attached to housing, are another possible next step for reform, the panelists said.

Mexico City Mayor Miguel Mancera's efforts to reduce parking requirements could offer some lessons for NYC policymakers. Advocates there won public support for the reforms by showing "real numbers" that explain how the money spent on parking could instead fund housing or transit, according to Andrés Sañudo of the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy's Mexico City branch.

"If we are able to show [citizens] that there are other mechanisms on which we can... finance transportation or to finance affordable housing, I think it can be easier," Sañudo said.