Where is the outrage?

A 10-year-old Hasidic girl was killed by a driver on her way to school last month, yet unlike other community members who demand change after their most vulnerable road users are killed, there remains silence in South Williamsburg.

“Accidents happen,” multiple residents said.

But Yitty Wertzberger's killing at Wythe Avenue and Wallabout Street was no accident. The intersection is known to be a dangerous spot in a neighborhood where there have already been two other road deaths this year — an alarmingly high number for such a small enclave. Given the numbers, the lack of outrage from the mostly Hasidic neighborhood is shocking. There is virtually no pressure from local community leaders on the Department of Transportation to fix the deadly streets.

In fact, the most vocal of those leaders, longtime Community Board 1 member Simon Weiser, opposes pre- or post-crash safety intervention because, he says, he doesn't believe they work.

“Some people take every accident and they want DOT to stand on their head,” Weiser, the vice-chair of the CB1 Transportation Committee, told Streetsblog.

If there was ever a reason to stand on one's head, the death of 10-year-old Yitty Wertzberger might qualify. She was on her way back from school when the driver of an SUV — the vehicle of choice in South Williamsburg, where family sizes are large — got frustrated waiting behind other cars in traffic on Wallabout Street, so he crossed the yellow line on the two-way street, raced westbound in the wrong lane, turned left onto Franklin Avenue and ran right over the girl.

It was no "accident": there have been 24 reported crashes at that very intersection in just five years, injuring 11 and killing one, according to city data compiled by Crashmapper.

Community response

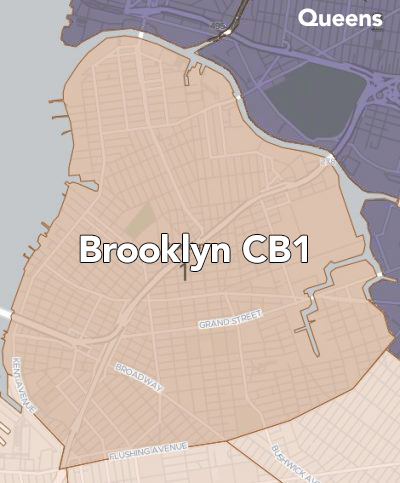

Brooklyn Community Board 1 comprises Williamsburg, East Williamsburg and Greenpoint — some of which have residents who are intensely focused on making New York City roadways safer.

But some communities, such as South Williamsburg, are not interested. When the Transportation Committee met just two days after Yitty was killed, not a single member of the public showed up to discuss the incident and the need for change.

“Sadly, ... we proceeded with our normal agenda,” said Paul Kelterborn, a resident of East Williamsburg and a member of the Transportation Committee “That’s the sad thing about it, it's just a routine.”

Across the city, especially when children have been killed by drivers, death is not simply business as usual. In Park Slope, after a driver ran over 19-month-old Joshua Lew and 4-year-old Abigail Blumenstein, more than one hundred angry protestors chased down then-mayor Bill de Blasio at his gym to demand action. (And they got it.)

This year in Queens, after a driver killed 8-year-old Bayron Palomino Arroyo, more than 700 people marched to put an end to senseless traffic violence. (At least that driver was charged — and his recklessness was part of the reason that lawmakers in Albany finally passed a bill allowing New York City to lower its speed limits.)

In October, when 7-year-old Kamari Hughes was killed in the crosswalk by an NYPD tow truck, an open letter to Mayor Eric Adams garnered almost 4,000 signatures. (Street safety improvements, in the form of daylighting, were made in the wake of the protests.)

There are no such rallies in South Williamsburg. It has been more than a month since Yitty’s death and instead of protests, in fact, people are resigned to the status quo of unsafe, car-choked streets.

“Crossing is always going to be an issue with children,” said one Hasidic woman standing with a group of mothers at Wallabout Street and Bedford Avenue.

At a nearby children's clothing store on Wallabout Street, the store clerk said that e-bikes were the neighborhood's biggest safety concern. When asked if she thought cars made it dangerous for children to cross the street in South Williamsburg, she said, "Well, that's anywhere."

South Williamsburg mothers clearly love their children just as much as other mothers. But many simply don't make the connection between preventative street safety measures, that would result in less parking, to less traffic violence, said one Williamsburg leader.

"It's horrible, things should be done to prevent other deaths," said Bella Sabel, a member of the Hasidic community who has lived in South Williamsburg since the early 1960s. Sabel got involved in the community board six years ago because she was concerned about congestion where she lives on Kent Avenue.

"I'm sure they are worried," said Sabel when asked about how mothers in the community are feeling. "I thank God that a day goes by and nothing happens, because it's very congested."

But Sabel, and others who may care about street safety, have little power on CB1. Weiser, who has been vice-chair for over two decades, has been the spokesman for the Hasidic resistance to street redesign that prioritizes people over cars. He is one of the reasons why residents of the city voted to install term limits for board members, lest neighborhood panels fail to change as neighborhoods do. (The term limits were phased in, so they won't affect Weiser for a few more years.)

"[Simon] will be one of the people who will be gone," said Ryan Kuonen, who was a member of Community Board 1 for 10 years. "The public was very clear [in the term-limit referendum] that people shouldn't be able to build this power base, but the power base still exists. The people clearly said, 'We want term limits,' but in CB1, all they've done is try and figure out a way to not have them be applied."

So who is Simon Weiser?

Street safety organizers North Brooklyn have clashed with Weiser and the Hasidic community in the past. In 2009, Weiser played a key role in the removal of a bike lane on Bedford Avenue between Flushing and Division avenues. So activists repainted it (albeit temporarily).

Weiser was also a vocal opponent to Citi Bike infrastructure in South Williamsburg, he opposed the Kent Avenue protected bike lane, he fought against the Make McGuinness Safe Campaign, and, most recently, he objected to a resolution banning parking at corners, a pedestrian safety strategy called "daylighting."

Daylighting was approved at the committee level in October. The full board vote was then stalled by Weiser and others in opposition until the measure failed in February. It was sent back to committee and finally passed at the full board meeting last month, partially because of Yitty's untimely death.

“There was pushback from people concerned about losing parking spaces,” said William Vega, a member of the Transportation Committee. “But when we lost this young girl, everybody got on the same page. She was the catalyst.”

Revanchism by longtime board members like Weiser — who was first appointed by a borough president who isn't even alive anymore — is what some board members say makes CB1 slow to solve street-safety problems. In the case of daylighting, the board ultimately agreed to a very watered-down version of the original proposal.

“When DOT comes to us with a watered-down version of something, we water it down even further,” said Kelterborn, ruefully.

Each time there is a death, Weiser has attempted to use his community board position to stall or scrap proposed safety measures by focusing on the details of each crash and suggesting that conclusions can't be drawn because each crash is unique.

When beloved teacher Matthew Jensen was killed by a driver on McGuinness Boulevard in May, 2021, Weiser victim-blamed and then complained that the city took action to make the roadway safer and reduce speeding:

“You know, I don't like to bring this up,” he said. “But we don’t know the story on McGuinness Boulevard, with the teacher. They redo the whole street because somebody got killed. He didn't cross at the intersection. It's terrible to lose a life, but at the same time, mistakes happen.” (In fact, we do know what happened in this crash). The driver who hit Jensen was speeding, he was charged with criminally negligent homicide, leaving the scene of a crash, reckless driving and speeding — not an accident at all.

In the case of Yitty, Weiser told Streetsblog that he wouldn’t know who was at fault until he saw the report. He said that the street was already daylit, which it is not.

This view from community leaders trickles down to everyday people living in South Williamsburg.

Even Sabel channeled Weiser's victim-blaming: "I wasn't able to hear the real cause of her death, whose fault it was, and why it actually happened," she said.

In fact, driver Isaac Karczag was arrested and charged with failure to yield, failure to obey a traffic device and failure to exercise due care — charges that, at least from the perspective of police, show whose fault it was. His next court appearance is on July 1.

In 2020, 35-year-old cyclist Sarah Pitts was killed by a driver on Wythe Avenue and Williamsburg Street East — an area where the painted bike lane is routinely blocked by Hasidic school buses. As a result, the DOT said it would install jersey barriers to protect cyclists and prevent illegal parking, but Weiser fought it. At a meeting discussing the changes, Weiser insisted on focusing on the exact details of the crash, asking why changes should be made based on this one “accident."

“It's important to understand, you can do so much for safety, but it isn't always going to make a difference,” Weiser told Streetsblog.

Of course, there are members of the community board who think energy should be spent preventing these deadly crashes rather than just blaming the victims or carrying on with business as usual.

“It's not our job in the community to find out who’s at fault, it’s our job to make these streets safer,” said Vega.

And obviously, street safety advocates push for changes before a death occurs — a foundation of the city's Vision Zero initiative.

“Most people only envision crossing guards as the safety feature of choice, but there are other options to protect kids going and coming from school. One option is building school streets, which can allocate a limited amount of car access during school hours,” said Amber Adler, a member of Families for Safe Streets and of Flatbush’s Orthodox Jewish community.

But Weiser and others on Community Board 1, who are concerned about losing parking spots, focus on each death as if it is a mystery to be solved, instead of a systemic problem.

“We can spend all of our time just chasing after, retroactively, what went wrong in each instance,” said Kelterborn, “That’s kind of a stall tactic, we’re just burning through time that way.”

How dangerous is South Williamsburg?

South Williamsburg is the land of double-parked cars. Streets within the Hasidic enclave are crowded with large vehicles, school buses, and pedestrians, creating a dangerous situation for those walking or riding a bike. Many in the Satmar Hasidic community have large families, so there are more kids walking around the car-filled streets, and sidewalks — which often serve as impromptu parking for a minivan, or six.

“We all know that there are greater safety risks with larger cars. And because this community has larger average family sizes they require larger cars to get around. And that inherently poses some risks that we have to navigate,” said Council Member Lincoln Restler, whose district includes South Williamsburg.

South Williamsburg’s population is around 27 percent children under 9 — almost triple the citywide average, according to the most recent U.S. census data. But the irony is that the Hasidic community in South Williamsburg may not need their cars after all, according to census data.

In a city where only 9 percent of residents walk to work, 35 percent of South Williamsburg residents do so — having achieved their own version of the 15-minute city in their small enclave with its own grocery stores, hospitals, doctors offices, places of worship, and even its own volunteer police and fire departments.

But somehow, car ownership is very high.

"We have families and there's always appointments, everybody has their own reason. The younger generations they need a car," said Sabel, adding that she knows some families who don't move their cars for two weeks at a time because parking is so hard to find.

South Williamsburg is densely populated, with a population density three times the city rate. An area with similar density, the Lower East Side/Chinatown has half the number of cars (30 percent of households vs. around 15 percent in Lower East Side/ Chinatown). The amount of cars, the density of the neighborhood, and the number of children is creating a deadly reality.

Before Yitty, there were two other traffic fatalities in South Williamsburg — a cyclist was killed on Bedford Avenue and Lorimer Street, and just a block away a driver was killed on Lorimer and Harrison Avenue. In the last 10 years there have been 14 traffic deaths in South Williamsburg. On Wallabout street, which stretches from Classon Avenue to Broadway, there were 97 injuries from reported crashes in the last five years. On a similarly sized street in Greenpoint, Nassau Avenue, there were 52 injuries, according to data compiled by NYC Crash Mapper.

What's next for Wallabout street?

After fatal crashes, the DOT conducts an analysis of the crash site to see if changes can be made to prevent future deaths. Restler says that he is hoping to see improvements to the area.

“I think they are considering some improvements around turning at this intersection and changes in traffic patterns that I believe could make a real difference in advancing safety for young people,” said Restler.

The department has not responded to Streetsblog's request for information about their analysis.

Despite his history of pushing back on DOT’s proposed changes, Weiser told Streetsblog that he would support what the department brought to the table ... if it could show that something would have prevented Yitty's death.

Kelterborn is convinced nothing will happen because of cognitive dissonance within the Hasidic community.

“When we talk about South Williamsburg issues in the Transportation Committee it's really about preservation of parking. But at the same time, oddly, we hear that they’re overwhelmed with congestion. They can't really seem to put together that one leads to the other,” said Kelterborn.