STOCKHOLM — New York City is about to launch congestion pricing, which means we're in the so-called "Valley of Political Death," which means it was time to talk to Jonas Eliasson.

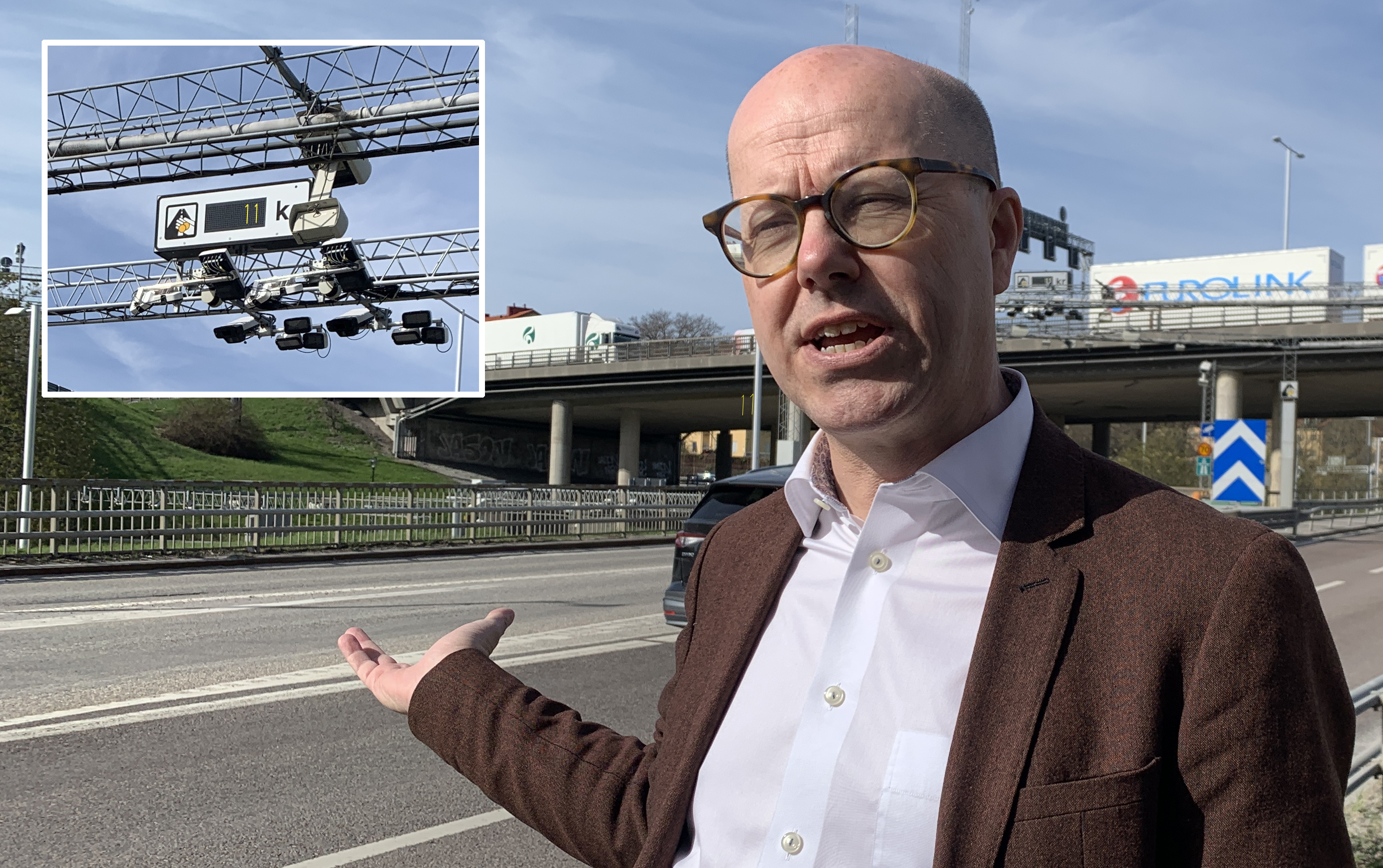

Two decades ago, Eliasson — an academic and urban planner — became Stockholm's point person on implementing this city's congestion pricing plan, which levies relatively small tolls to enter the center part of this island metropolis by car. The tolls are highest — but still just $3.25 — during the peak times, but drop to as low as $1 during the say. Tolls are capped at around $10 per day.

Like New York now, congestion pricing was deeply unpopular as a concept in 2004 and 2005 when it was being planned.

"People said, 'Why are you taxing me to do something I've always done for free,'" Eliasson told me this week. "But then when it is implemented, and people can see that it works, it becomes very popular."

He reminded me that after a six-month test of congestion pricing in 2007, a referendum of Stockholm residents affirmed support, but only by a slim majority. But in the successive decades, support has grown to over 70 percent.

Indeed, as I've wandered around Stockholm this week — and I've wandered far, thanks to a rental bike and an obsession for lutfisk — I've met many young people who don't even think about the congestion pricing, evidence that two decades in the political desert has brought this city's residents to the promised land.

I've encountered some mild resistance from some older car owners who feel put upon, but when pressed, they, too, admit that the city is a better place. So many roads have been able to be turned into pedestrian zones, dedicated bus lanes, or protected bike routes that now bikes outnumber cars in the main parts of town and now bus speeds are twice what they are in New York City.

So how can we get to a point where people understand the benefits of congestion pricing even before it's implemented? That's why I looked up Eliasson, who remains a top official at the Swedish National Transport Administration (as well as serving as a visiting professor of transport systems at Linköping University and chair of the Planning & Construction committee of the Royal Academy of Engineering Sciences).

I've edited our conversation only for length, clarity and to translate my bad Swedish back into English:

Gersh Kuntzman: New York is in the valley of political death right now. Talk me through how you got through that.

Jonas Eliasson: Initially, people really didn't understand the concept of paying for road space. It was seen as something so strange. I imagine that's how people felt when someone introduced metered parking. They probably said, "We didn't pay for parking before, so why should we pay now? I'm not consuming anything." But after a while, people do see that they are consuming something. And it's true of the roads. It feels counterintuitive to many people, until they realize that it's actually the same thing when you pay more to take a flight during the busiest travel periods or to pay more for electricity during peak hours. And once you're used to it, it's as natural as needing traffic lights or speed limits.

GK: What's even more relevant is that until congestion pricing, you had no tolls at all in Sweden, so it must have been a great shock to suddenly pay to drive somewhere. But in New York, we have tolls on most bridges and in all the tunnels, so people are accustomed to paying — but it doesn't mean they like it.

JE: But they'll see two things. First, is the obvious reduction in congestion, which no one believed would happen. When people saw a 20-percent reduction, they said, "OK, so this is what they were talking when they said the congestion was going away." And you could see with your naked eye.

NOW: In our interview between @GershKuntzman & @EliassonJonas hear how Stockholm residents came to embrace congestion pricing.

— Streetfilms (Now 1,100+ films!) (@Streetfilms) May 13, 2024

3 1/2 minutes all NYC electeds, media & denizens need to listen to. @StreetsblogNYC @OpenPlans @RegionalPlan @MTA

WATCH HERE: https://t.co/RgZrimbukQ pic.twitter.com/yxG4pnJgcS

Second, the biggest thing is just the psychological effect of having to pay at all — we went from zero to a few dollars, which means people consciously make a decision each time they make a trip: Is it worth it today for this particular trip to use my car or should I take a bike today or take the bus? It's not like everyone abandoned their cars. But they suddenly made one-fifth fewer trips in their car because they were thinking about it.

It's a little bit like being at one of those candy stores where you fill a bag and then weigh it. If the candy is free, you'll take way more than you need or even want. But if the candy is 10 cents per piece, you will actually think, "How many pieces do I want? Maybe it's four or five." But it's not really about the money. It's just being forced to make a conscious decision of what is worth it for you in that moment. And traffic has stayed down, even as the population has gone up by 2 percent.

GK: I have to ask you this question because in New York, many people will cover their plate or scrape away a number, or take the paint off entirely so that the plate can't be read by our speed enforcement camers. And people in Stockholm tell me that no one would ever do that here. Is that true?

JE: I suppose if you have a forged license plate, you can, in theory, park for free forever. I suppose there are some professional criminals who do that. But here, you don't break the law. It's one thing to walk against red light, but there really is some resistance to a forged license plate.

GK: Really? Why is that? Because in New York, it's very common. Police officers do it, but also regular people do this.

JE: I have never seen this. And maybe it's because the congestion charge became less controversial because Swedes see that it works. And, to some extent, we have a fairly high trust in government.

GK: Yeah, we're sort of the opposite right now in the United States.

JE: I don't want to exaggerate because like anyone else, we know that government can be hapless or waste money, but people would not intentionally cheat in such a blatant way. And even though we speed on the highway, we do not speed past schools though. It's very frowned upon. So doing something to make your license plate unreadable, well, that would be like robbing a bank! And there's a clear social stigma of robbing banks.

GK: Yeah, we have that even in the United States. Let's move on. I understand the toll was raised in 2016 to its current rate. And now that money is going for buses and trains exclusively. Has that helped also with the perception of the toll?

JE: This gets into a conscious choice that the government made originally. From the start, the congestion toll money was used to build and maintain roads. I think that the goal is to show that they were actually spending the money in a way that benefited motorists rather than transit users, which might have been a good way to do it at the time politically.

GK: But the way our MTA is promoting it is to say that our toll will entirely be for transit, but all that's done is make drivers angry because they rationalize their driving by saying that the subways and the buses stink. Of course, they perceive it that way because they're drivers. And then even if the money is used perfectly and we get the transit improvements we've been promised, drivers won't care because they won't see them. They don't take the bus, nor do our elected officials.

JE: Many people in Stockholm don't even that the money is now going to support transit in Stockholm, but that's not the issue — the issue is that the money has bought to the support of Stockholm politicians, so they aren't going out and whipping up resistance anymore.

I'd also offer some advice about one mistake that was made when this was first proposed: it was introduced in a way to portray drivers in a very bad way. The campaign was not, "This is just a routine traffic planner policy measure," but more like, "Cars are destroying the world. They are destroying your children's future, etc." And, of course, that increased the polarization among people who drove at least sometimes. And many of those people never even drove into the inner city, but they felt they were being painted as evil. But here's why they did that: If there's no controversy about something, the upside for a politician to support it is small. In this case, they wanted to be out front with not just a little technical fix for traffic, but a campaign to save the planet. This increased the tension. But once the congestion charge was in place, it became non-controversial again.

GK: You've said in the past to Americans, "Just do it." Now we're on the verge of that. Do you still stand by that?

JE: Yes. Congestion pricing works. It works much better than you think. And it's much easier to adapt to it than people think. In Stockholm, people really thought that it would be the end of the world, the city will come to a standstill, no one would be able to get to work anymore and all the theaters and shops would just go bankrupt. None of that happened. And in 20 years, people won't even think about it. But, yes, at the start, this was the most controversial issue. Now, we just talk about tiny issues of how to make it even better.

But it works. It just does.