The MTA risks squandering the potential of the proposed Brooklyn-Queens Interborough Express light rail line if the agency runs part of the route on city streets instead of building a short tunnel under a Middle Village cemetery, argues a new report.

The current plan for the IBX light rail to emerge from its underground right-of-way near the boneyard and run on surface streets makes the train "far more vulnerable" to traffic delays than even existing bus routes in the area, the advocacy group Effective Transit Alliance said.

A 515-foot tunnel beneath All Faiths Cemetery, meanwhile, would increase the cost of the project "only slightly" in exchange for "enormous" service benefits, ETA said.

"The IBX must deliver fast, frequent, and reliable all-day service, on par with or exceeding that of the existing subway system," the group wrote in its report. "Current planning parameters, however, provide too little capacity for this new line, potentially fatally hamstringing its usefulness for riders."

Gov. Hochul last year announced plans to build the IBX on an existing, mostly submerged freight line between Bay Ridge and Jackson Heights. The project is currently in the design phase, but transit officials seem set on the street-running plan. The MTA has not contacted All Faiths about potential below-ground work, amNY reported in January.

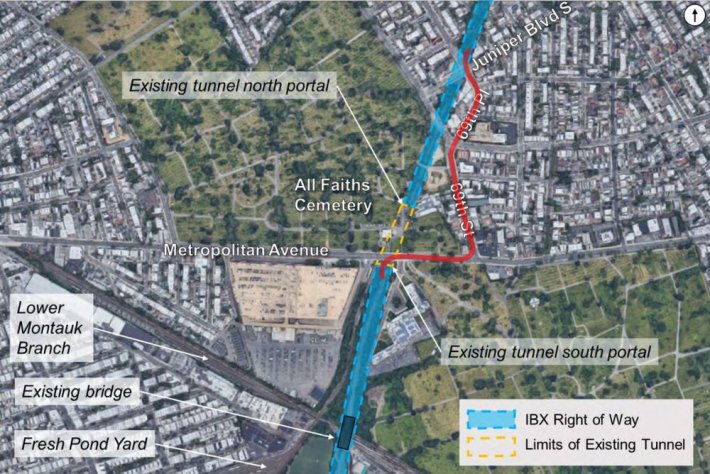

The Bay Ridge Branch's existing tunnel under All Faiths is currently the exclusive domain of freight trains operated by the New York and Atlantic Railway. The MTA wants to avoid sharing track operations with the current freight operation, which could lead to conflicts — especially if the proposed Cross Harbor Freight Tunnel is ever built and even more freight trains run on the Bay Ridge Branch.

To avoid the need to build a larger tunnel, the MTA's preferred plan for the IBX is to circumvent the cemetery and run passenger trains along Metropolitan Avenue, 69th Street and 69th Avenue in Middle Village (red lines on map below)

But the downsides and difficulties of creating effective street-running rail weigh heavily on the success of the project, according to ETA and other observers.

On the one hand, without separation from on-street traffic and signal priority at traffic lights, the transit line risks getting caught in the madness of central Queens traffic. On the other hand, instituting that transit-first right of way could mean massive changes to the street geometry and taking away parking — exposing the MTA to a massive political fight.

According to ETA, the MTA has several options for building the tunnel: It could "cut-and-cover" as proposed in the initial Interborough Express study done by the engineering firm AECOM and dig an 18-foot-deep trench, build the tunnel, then cover it up for $40 million. However, that tunnel that might require moving a mausoleum in the trench's path, perhaps only temporarily.

Any work in the graveyard could be done with respect to the families of the people buried there, according to ETA Executive Director Blair Lorenzo. Moving future resting places for the dead may be easier than moving parking spaces used by the living, she added.

"We haven't gone in depth into an analysis of the politics of the mausoleum as of yet," Lorenzo told Streetsblog. "Our operating assumption ... is that there is and will be far more opposition to street running than disturbing a small mausoleum with significant amount of empty space."

AECOM also studied what it would take to build a deeper, 60-foot deep, 1.5-mile long tunnel that wouldn't disturb the mausoleum and is more suited for conventional subway trains. The consultants said the tunneling and a needed underground station to go along with it would add billions to the $5.5-billion project.

But the ETA report suggests the MTA build a 30-foot deep cut-and-cover tunnel to get under the mausoleum without disturbing it. Doing so would require a steeper incline than is typical, but not unheard of, in the MTA system — the 7 train makes a similar climb when it enters Queens from the East River.

A cut-and-cover tunnel would avoid the high prices that come with tunneling in New York City, allow the Interborough Express to run 10-percent faster than the MTA has planned and possibly enable larger train cars to carry more riders.

The smaller cars of light rail that would be required for on-street transit mean the MTA could fail to meet its own ridership projection even if it ran trains every five minutes — hardly a guarantee given the potential car and truck traffic and the MTA's current plans to only run trains every 10 or 20 minutes.

"To meet the projected demand, it will almost certainly be necessary to run longer or more frequent trains, or both," Lorenzo said. "Not having to run on the street also allows the MTA to have access to a larger size of light rail vehicle should they choose."

The new report isn't the Effective Transit Alliance's first push for a tunnel under the graveyard. A prior report, Interborough Express Done Right, was dismissed by the MTA because its author Alon Levy is not an engineer.

This time, a spokesperson for the MTA said that the tunnel idea isn't dead yet — and that the agency will share more specific analysis about the feasibility of a tunnel and potential designs for on-street transit when the recently funded engineering phase of the Interborough Express is finished.

"No final determination about the feasibility of a tunnel north of Metropolitan Avenue has been made," MTA spokesperson Mike Cortez said in a statement.

"The engineering phase of the project ... will include additional exploration and analysis of specific alignment options, including constraints of potential tunnel construction and street-running engineering."