Four Brooklyn neighborhoods that were named Vision Zero “Bike Priority Areas” in 2017 still haven’t gotten any new bike routes — part of a group of 10 community boards that the city vowed to improve, yet still trail the rest of the city for bike infrastructure and have poor safety records as a result.

Roads in Borough Park, Midwood, Flatbush, and Bedford-Stuyvesant remain unsafe for cyclists because the city’s progress on bike lanes is not evenly distributed, even among DOT’s priority areas, according to an analysis of the city’s open data portal. The slow progress frustrates advocates and community members who want safe biking connections.

“Why [do] streets in other priority bicycle districts deserve protected bike lanes, but not in these neighborhoods in South Brooklyn where consistently a lot of people do bike?” asked Liz Denys, the campaign lead for Flatbush Streets for People. “A lot of people continue to get injured or killed because they keep failing to act.”

DOT did not respond to requests for comment specifically about the bike priority districts. Previously, the agency has said that it is prioritizing its street improvement projects based on the equity formula outlined in the Streets Plan.

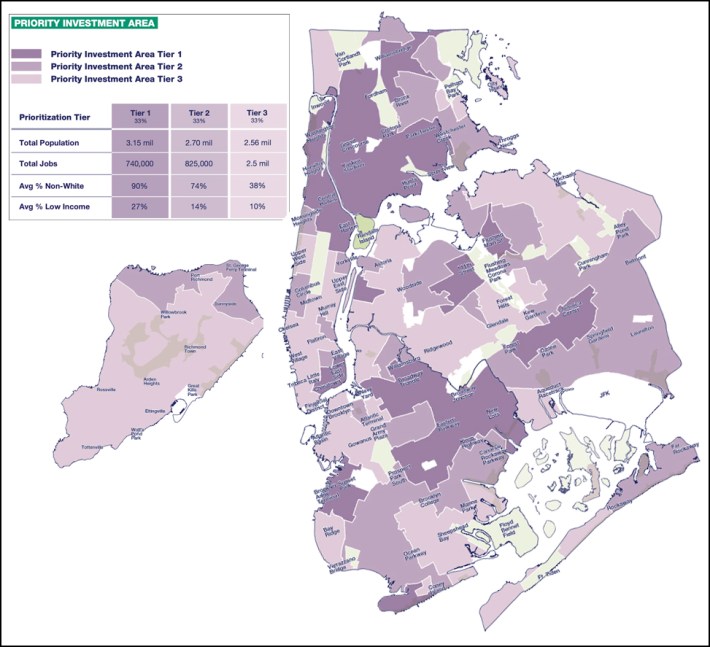

DOT said earlier this year that it had completed more than 150 "street redesign projects," which comprises a broad variety of changes that sometimes include bike lanes, in its "priority investment areas," Tiers 1 and 2 (see map, left). The agency said that as a result, there has been a 30-percent drop in fatalities involving Black victims over the last two years.

But parts of the Tier 1 priority zone includes the community boards that have gotten no protected bike lanes. The remainder are in Tier 2 zones.

A little history

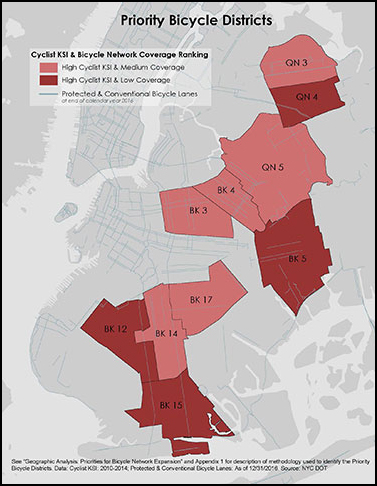

Back in 2017, DOT identified priority districts for cycling based on danger to cyclists — those neighborhoods made up just 14 percent of the city’s bike lanes, but 23 percent of cyclists injuries and deaths. The city promised to create or enhance 75 miles of bike routes in those areas by the end of 2022.

The city’s bike network has big gaps in crucial stretches of Brooklyn (click around on the interactive map below).

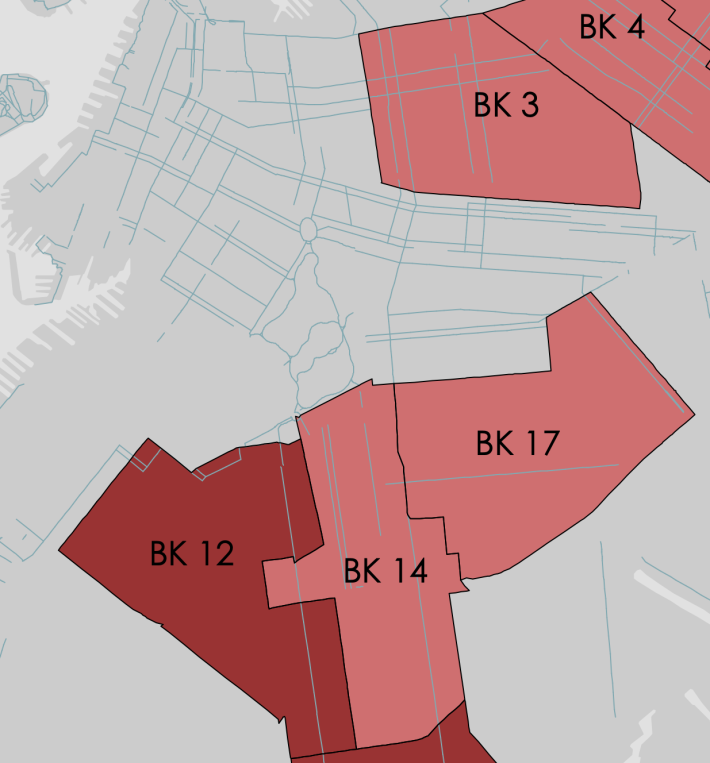

Priority districts in Queens, East New York, Bushwick, and Coney Island have received 56 miles of new routes since 2017, according to analysis by graduate researcher Kara Stoley. But there has been zero expansion of the network in Flatbush, Midwood, Borough Park, and Bedford-Stuyvesant — whose four community boards were all labeled as "high" need in the 2017 report.

The slow progress alarmed residents and even elected officials, who have been active in advocating for more bike lanes.

“DOT takes too long. But those other neighborhoods got their bike lanes, [so] now it's our turn.” said Council Member Rita Joseph, who represents large portions of Flatbush and Midwood. “We've been getting a short end of the stick and we want that to change.”

Last year, Joseph introduced a bill that would spur DOT to accelerate the pace at which it is building protected bike lanes, from 50 miles a year to 100.

Joseph's colleague to the north, Council Member Chi Ossé is also getting impatient.

“This failure is yet another glaring example of the administration falling far behind on its commitments to develop bicycle infrastructure in our city,” Ossé wrote to Rodriguez last year after the Bedford Avenue protected bike lane was delayed. On March 16, Ossé rallied with community members over the delays, which, he said, is the result of the DOT claiming it needs to do more community engagement.

Advocates say that City Hall, not DOT alone, is to blame.

“You have places even where there is strong City Council support [for bike lanes], [but] also near to the core Adams territory where people see this stuff and torpedo it,” said Jon Orcutt of Bike New York.

As Streetsblog reported last year, Mayor Adams created a rogue chain of command led by Brooklynite and street safety opponent Ingrid Lewis-Martin to stall or kill bike lane projects that she doesn't like.

A safety and equity issue

The lack of safe infrastructure has deadly costs. Since 2017, 3,417 cyclists were injured and 18 were killed in Brooklyn community boards 3, 12, 14, and 17 which cover those neighborhoods, according to city stats. Those four community boards have just 3 percent of the city’s bike routes, but 10 percent of the bicyclist injuries and 12 percent of bicyclist deaths since 2017.

Sometimes, the DOT has appeared to act, but has failed; in 2021, the agency presented a plan to add additional east-west connections through Community Board 14. None of the lanes would be protected, so residents demanded more safety, but DOT didn't provide the enhanced lanes.

“There’s no plans to actually implement any of the protected bike lanes we badly need; in my opinion, a connected protected network of bike lanes is the minimum,” said Denys.

On the flip side, some powerful pols objected when DOT sought to add bike lanes in CB17 in 2021 — but those weren't even protected lanes.

As a result, these four Brooklyn neighborhoods have far fewer protected bike lanes than the city’s network as a whole, data analysis by Streetsblog shows.

Flatbush is also due for Citi Bike expansion this year. The neighborhood needs a viable bike network to maximize its impact.

“There's also been a lot of extra concern through both bicyclists and non bicyclists about Citi Bikes coming to the area without an adequate amount of interventions to protect those bicyclists and make sure streets are easy and clear for all people,” said Denys.

As the Council considers monitoring the Adams administration's failure to meet the legal benchmarks of the city's Streets Plan, it will be crucial to hold the city accountable for not just how many miles of new lanes get built, but also where they get built — an issue of equity.

“It becomes what we always talk about — equity and access,” said Joseph. “My community has been asking for it. The Commissioner has made a commitment. He needs to step up and do it now.”

— with Gersh Kuntzman