This is their New Year’s resolution.

State lawmakers are eager to trek back up to Albany next year to finally pass a bill that would allow New York City to set its own speed limits — which legislators have failed to do for four years in a row.

Last year, despite the overwhelming support of Gov. Hochul, the state Senate, Mayor Adams and the City Council, plus a nearly unprecedented hunger strike in the state Capitol, Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie (D-Bronx) refused to allow the lower house to vote on the bill, known as Sammy’s Law.

But even after that crushing defeat, the bill's supporters are coming back stronger — especially on the heels of one of the deadliest years for traffic violence in the Vision Zero era.

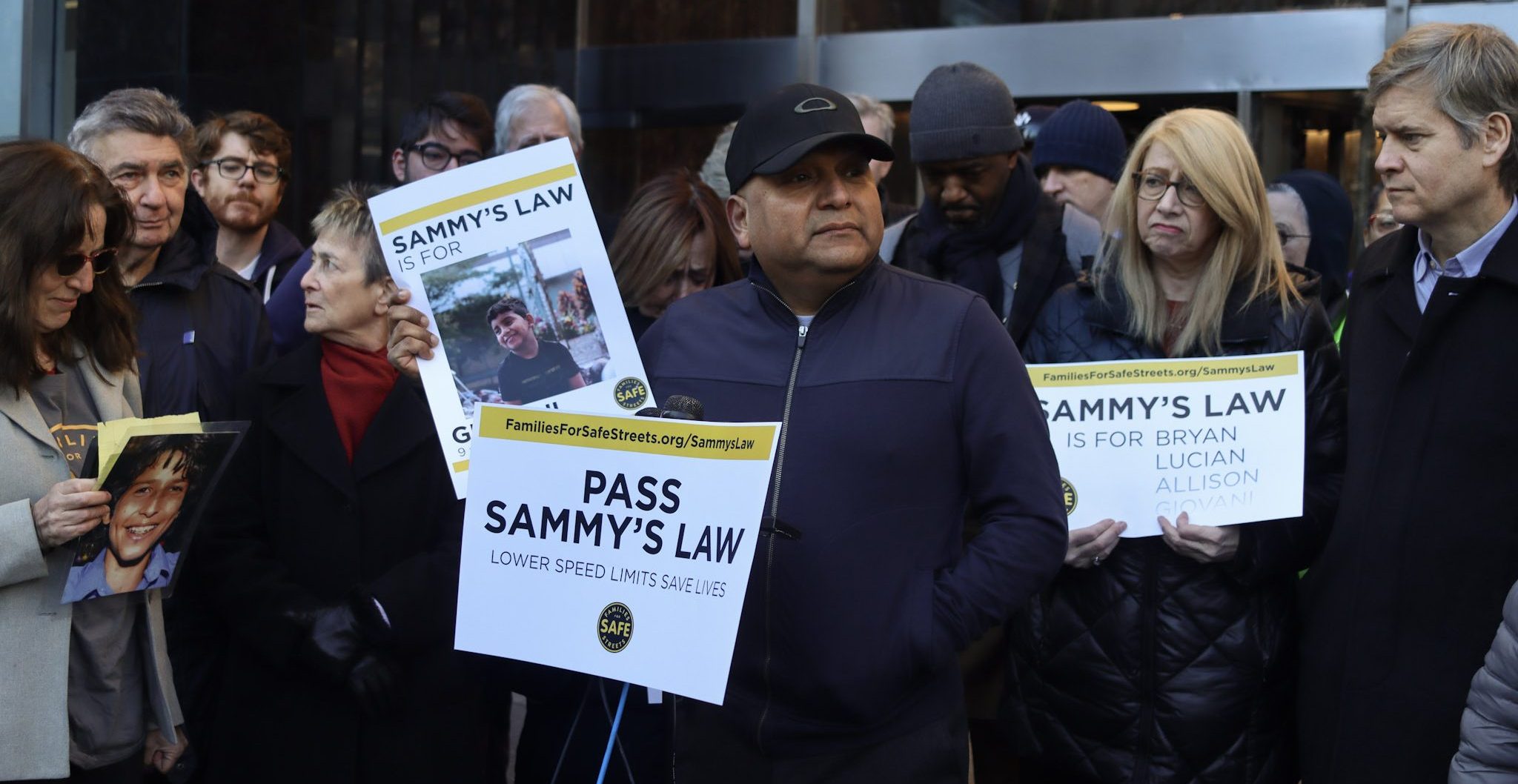

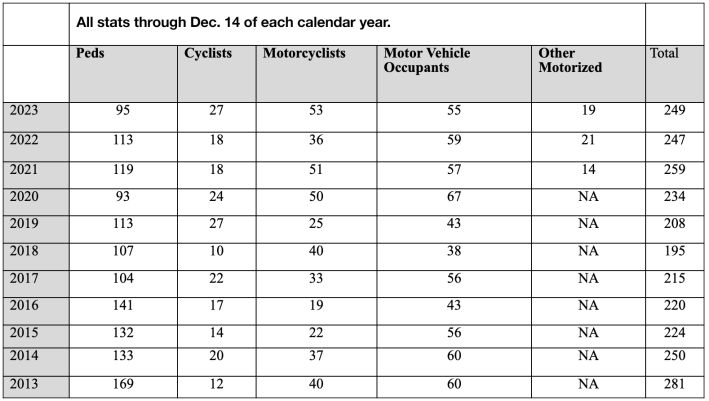

“We’re not giving up,” Upper West Side Assembly Member Linda Rosenthal, who carried the bill in the lower chamber, said at a rally outside Heastie’s Manhattan office on Friday. “Last year, 257 people were killed on New York City streets by reckless and speeding drivers. ... Each of these deaths was preventable. This horrifying statistic demonstrates the urgent need to pass Sammy’s Law.”

Slower speeds save lives.

— Families For Safe Streets (@NYC_SafeStreets) December 15, 2023

Today, we joined elected officials and street advocates to call on Albany to pass #SammysLaw.

No more delay. pic.twitter.com/3wW1JyWxX8

Rosenthal was flanked by half a dozen of her colleagues in both houses, city officials, advocates and grieving parents — including Amy Cohen, whose 12-year-old son, Sammy Cohen Eckstein, was killed just steps from his Brooklyn home in 2013 and in whose memory the bill was written. All attendees demanded the bill get another chance come January, when session in Albany resumes.

“We can’t wait any longer. People like Sammy, and so many others are dying on our streets. This is not Sammy’s law, this is also Giovanni's law, and Kevin's law, and the law for all children who are dying in traffic violence, for seniors, for peoples’ spouses and loved ones,” said Cohen, referring to 9-year-old Giovanni Ampuero, who was killed by a hit-and-run driver in Queens in 2018; and 13-year-old Kevin Flores, who was riding his bike when he was killed by an oil tanker in Brooklyn the same year. “We cannot let this go on.”

Hochul had signaled her support for Sammy’s Law last year during her State of the State address, but it failed to move forward in the budget. Lawmakers had another opportunity to pass it in the more traditional "how a bill becomes a law" way, but that didn’t work either, thanks to Heastie, even though the bill had enough sponsors to earn passage — if, of course, those sponsors indeed supported the bill.

It was just the latest failure. In 2022, when the Senate was poised to pass Sammy’s Law, the New York City Council failed to support it in the form of a "home rule memo," which is required for bills that affect specific municipalities. And the year before that, the Senate did pass the bill, but the Assembly skipped town for the summer before voting on the measure.

Lower speed limit saves lives, advocates say. After the city got permission to lower its speed limits from 30 miles per hour to 25 mph (and 20 mph in school zones) in 2014, there was a 36-percent decline in pedestrian fatalities, advocates said. The bill on the table now would not automatically change the speed limit, but would merely allow the city to do so.

Rosenthal declined to name the hold-outs against the bill, but said she and her colleagues are working on getting their support.

“There were people from different areas of the city that are heavily car dependent. They believe they need to protect the rights of some car owners,” said Rosenthal, who also hinted at a few minor changes to the legislation, like adding an education campaign component. “We’re tinkering around with it and we will have a more final version soon.”