Like most Democrats running for office in 2021, Eric Adams wholeheartedly endorsed an idea of continuing to tilt the balance of city streets away from private cars. Maybe he didn't vow to get rid of half of the city's parking spots, but he talked up building Paseo Park, expanding open streets to less well resourced neighborhoods, and meeting the ambitious goals of the Streets Master Plan. In fact, candidate Eric Adams even promised to go well beyond the streets plan, promising 300 miles of protected bike lanes and 150 miles of bus lanes by the end of 2025.

So to paraphrase one of his popular predecessors, how's he doin'?

The good

Although the phrase "The Pedestrian Mayor" sounds like an insult or a backhanded complement at best, Adams's rhetoric bore fruit when it came to pedestrian safety, as the year ended with the third-fewest pedestrian deaths since the city began recording the figure in 1910.

The Adams administration blew past its goal of upgrading 1,000 intersections this year, ending with upgrades at 1,400 intersections across the city. While many of the upgrades were simple changes to signal timing, the small things obviously count: there were fewer dead pedestrians than in 2021, 2019 and 2016.

Adams also advocated and won other safety improvements, such as speed- and red-light camera expansion that even the mostly new City Council didn't fully get behind. Adams wasn't able to help get enforcement mechanisms like insurance company notification or license revocation into the final law (if he even wanted such things), but it's easy to envision the expansion falling flat with a mayor more sympathetic to the crocodile tears of city representatives who saw the cameras a cash grab and not a safety tool.

Adams also expanded the range of what was possible when it came to open streets. It wasn't easy to get there, though, as the year started with a baffling effort to secretly dismantle part of the Willoughby Avenue open street. The mayor never said who gave the order or how any rogue anti-open streets elements in his office managed to get things as far as sending trucks to take down signs and remove planters from the street, but after that February surprise things generally moved in the right direction.

The city opened 46 new open streets, according to the DOT, and also ignored ugly and bigoted opposition to Paseo Park in order to move forward on the city's gold standard for open streets in Jackson Heights. Open streets were expanded by four hours and almost 50 locations for trick or treating on Halloween (even as the same bigoted opponents of Paseo Park showed up to yell about that too), which people have asked for for years, and Fifth Avenue in Manhattan was turned into a pedestrian-friendly winter wonderland on Sundays in December.

Adams also kept up the momentum on the city's bike rack installation, including a commendable effort to daylight 100 intersections with the bike corrals. As Bike New York pointed out in a tweet though, it's unclear what the city's next step is for bike parking. The Oonee Mini demo that brought the bike storage pod to five neighborhoods around the city this year drew praise wherever it landed. But beyond that, the DOT hasn't said what the agency learned from the pilot or what the future holds for either Oonee or another municipally connected bike parking idea.

The program didn’t meet its 5,000/year goal, but we’ll take the life breathed back into bike parking as a win. The big question is where the city’s bike parking efforts go from here pic.twitter.com/rHjxGmc5QM

— Bike New York (@bikenewyork) December 28, 2022

Credit where it's due, after all the grief Bill de Blasio got for never been seen on the bus or subway, Adams was a visible presence on the bus and subway. Hopefully we'll see him on a bike more next year.

The bad

Adams and his team talked a big game that he simply hasn't lived up to. Last December, even before Adams was sworn in, Ydanis Rodriguez, his incoming transportation commissioner, promised to harden half of the city's plastic-protected bike lanes in 100 days. By February, the timeline on the vow stretched to hardening those 20 miles by the end of 2023, a goal the city is meeting.

In any other year, building 25 new miles of protected bike lanes would be a cause for widespread celebration. But Adams the candidate promised an astounding 300 miles of protected bike lanes in just four years, which would amount to 75 miles per year in his first term. Projects like Schermerhorn Street and Emmons Avenue are rightfully held up as highlights for the year, but unless Adams recalibrates or suddenly gives his beleaguered DOT the staff and cash it needs to even hit the 50 miles of PBLs required annually by the Streets Master Plan, his own boast will haunt him at every year-end roundup.

The Adams administration did pledge $904 million towards the first five years of the Street Plan — more than the $1.7 billion the DOT once said it would need over 10 years — so it's fair to ask why the administration came up so short.

"By investing $904 million, Mayor Adams and the City Council showed their commitment to confronting traffic violence and creating safe streets," said Elizabeth Adams, senior director of advocacy & organizing at Transportation Alternatives. "However, the failure to meet the requirements for year one is a troubling sign. Moving forward, New Yorkers need to see concrete plans and the political will from this administration to ensure the requirements are and continue to be met on this ambitious and life saving plan."

Bus riders continued to get shafted in 2022, a rare bit of continuity between Adams and former Mayor Bill de Blasio. The results are plain: buses that were stuck at 8.1 miles per hour under de Blasio move at ... 8 miles an hour still according to the MTA. Coming into office, Adams said he would install 150 miles of dedicated bus lanes in just four years, and he was going to turn SBS service, with its dedicated bus lanes and all-door boarding, the baseline for bus service in the city.

But the reality is quite different:

- the city built just 11.95 miles of new or camera-protected bus lanes this year.

- The Fordham Road busway is being sent back to the drawing board again.

- The mayor's Office of Intergovernmental Affairs was reportedly a driving force in delaying the completion of the Northern Boulevard bus lane.

- The mayor trimmed the hours on more busways (two) than he created (zero).

Such a spotty record makes advocates wonder if the so-far-unnamed bus improvement project on Flatbush Avenue will actually get done.

"I’m looking forward to seeing Mayor Adams deliver on his commitment to better bus service in Brooklyn and I couldn’t be more excited to see paint on the ground for the desperately needed Flatbush Avenue bus lane," said Council Member Rita Joseph, who represents a stretch of Flatbush Avenue where the B41 struggles along under 8 miles per hour for much of the day.

The ugly

Start with the obvious: Even though pedestrian deaths went down compared to last year, total traffic deaths were at 248 on the cusp of the end of the year, lower than last year, but the third most deaths since the Vision Zero era began in 2014.

Beyond those cold numbers, regular old governance issues and horse-trading politics sapped the life from some important safety and transit initiatives outside of just Northern Boulevard. The administration also stumbled in areas with fewer public-facing metrics. The city treated its School Streets program, which allows schools to create open streets in front of its buildings, as an afterthought; as a result, participating schools fell from 101 schools in 2021 to just 47 as of December.

The city's one enforcement mechanism tied to speed cameras — a threat to impound cars that belong to repeat reckless drivers who fail to take a city safety course — was rolled out for only a tiny percentage of drivers, leaving tens of thousands of the worst recidivists in the city safe to continue endangering the public (only 12 cars have been seized).

Citi Bike's expansion in Maspeth and Ridgewood was held up for months, reportedly as a favor to Council Member Bob Holden, an Adams ally.

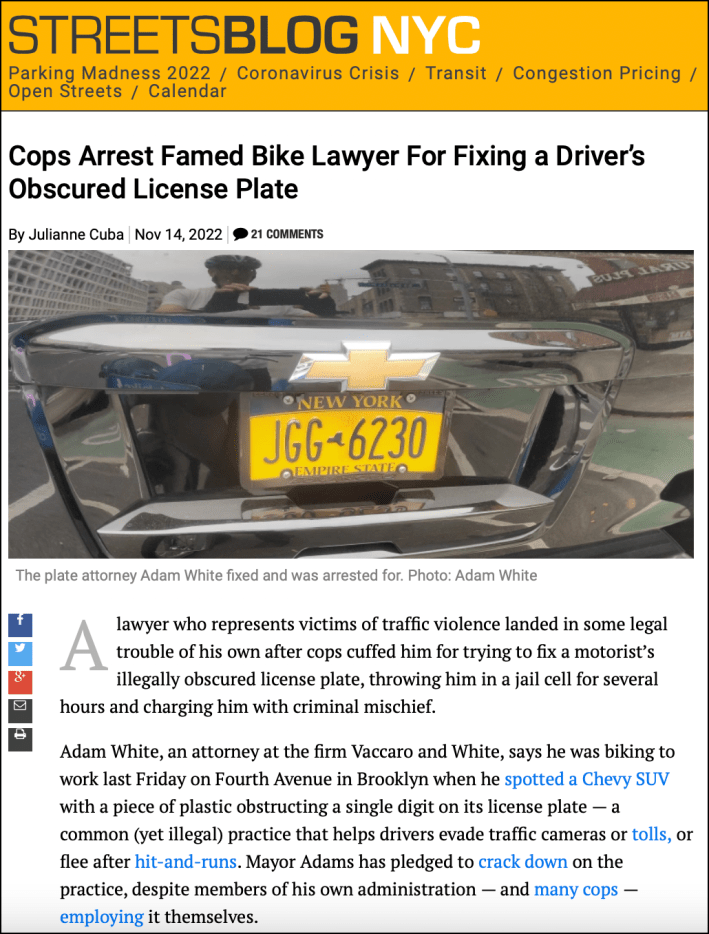

Adams said that his fight against "ghost cars" that are driven by people using fake license plates would be different from the past because, "I'm the mayor now." But ultimately, you could still find cars with fake plates parked near station houses with nothing done for weeks. Out of almost 60,000 complaints filed over fake or paper plates, police only issued 612 summonses all year.

And of course, placard abuse and 311 stalking continued unabated into the first year of the Adams administration. When he was the Brooklyn Borough President, Adams said he shouldn't be held to a standard that other borough presidents aren't held to on the subject. But now as the mayor, he could set the standard. Instead, police have basically gone unpunished for continuing to harass or ignore New Yorkers who make 311 complaints about illegally parked cars and made no effort to reform extremely obvious illegal parking happening all around City Hall.

The nadir of the year's total abdication on illegal parking was no doubt when a lawyer was arrested for removing an obvious illegal license plate obstruction from a car, only for the responding officer to shrug off the license plate obstruction itself.

After that, citizen efforts against fake or defaced plates became such a big thing on social media that the Times and Gothamist covered it. It's not a great look for the "get stuff done" mayor that normal everyday New Yorkers have begun to fan out to fix the problem.

I helped a neighbor of mine in @NYPD78Pct avoid those pesky tickets for having a defaced plate — and learned that he's got thousands of dollars in tickets, including lots of reckless driving infractions. And I'm the one who's guilty of CRIMINAL MISCHIEF??? pic.twitter.com/oFmVWe592m

— Gersh Kuntzman (@GershKuntzman) December 29, 2022

The future

The Adams candidacy was predicated on competence — that unlike his gangly predecessor, he would inject professionalism and entrepreneurial drive into a city government that would get shit done. So what are we supposed to think when the city comes up short on 30 miles of protected bike lanes and 20 miles of bus lanes, a year before it's supposed to start hitting 50 and 30 miles of each per year? Is that truly a "solid B+" — the grade Adams gave himself last week?

Adams has been fond of making the (historically dodgy) analogy that 2022 was his rookie year and 2023 will be his "Aaron Judge year," which is to say he will dominate governing in a way we haven't seen in at least 20 years. And to his credit, the mayor has loaded his future up with potential projects that if completed could actually result in a New York City that is more bike and bus-friendly than anyone has dreamed of. By 2024, we're supposed to see:

- A plan to cap the Cross Bronx Expressway

- A protected bike lane on Tenth Avenue in Manhattan

- A fully built out bus lane on Northern Boulevard

- A plan for a redesigned McGuinness Boulevard that includes shorter pedestrian crossings and a protected bike lane

- A bike network in northeast Queens

- A plan for Fifth Avenue that will bring long-delayed safety and transit improvements to the block and also make the avenue's wealthy business interests happy

- Badly needed bus improvements on Flatbush Avenue and beyond.

- A master plan for a citywide greenway network

New York is poised to be the beneficiary of "an effing lot of money" from the federal government for street safety and bike infrastructure efforts, including oodles of federal cash to help fill in the city's greenway gaps.

And on top of all of that, the "New" New York panel that Gov. Hochul and Hizzoner put together promised Adams would create an Office of the Public Realm to get these ambitious ideas over line, and specifically targeted car reduction as a goal to make the New York of the future fabulous and new New York City.

But ask any Met fan who's lived through not just one but two pitching rotations that were supposed to dominate baseball for years to come, and they'll tell you: potential is worth less than the paper on which the plans are printed.