U.S. gun deaths increased sharply in the first year of the pandemic, 2020, with the rise so steep among young people that the National Institutes of Health issued a bulletin this July calling gun violence “the leading cause of childhood death.”

That framing has been catching fire. In a major ad campaign, New York State’s largest healthcare provider, Northwell Health, has been calling out guns as “The #1 Killer of Kids.” Earlier this month the New York Times devoted its Sunday magazine to portraits of children killed by gun violence, which the paper described as “the leading cause of death for American kids.”

The New Yorker writer Jelani Cobb deployed the same framing in his “Talk of the Town” column leading the Dec. 26 edition of the magazine, castigating the Republican Party for making “access to firearms so obscenely sacrosanct that guns have become the leading cause of death for American children” (emphasis added). That Cobb is dean of the Columbia Journalism School and was addressing a somewhat separate subject than gun violence — his column was titled “Brittney Griner and the Role of Race in Diplomacy” — demonstrates how deeply this new mythos is permeating public discourse.

The portraits of gun violence victims in the Times are heartbreaking, the numbers damning. In an April letter to the New England Journal of Medicine, University of Michigan researchers reported that from 2019 to 2020, "the relative increase in the rate of firearm-related deaths … among children and adolescents was 29.5 percent — more than twice as high as the [13.5 percent] relative increase in the general population."

Any 30-percent jump in deaths among any group from any cause in a single year demands attention. That firearm-involved deaths among people younger than 20 increased by nearly a thousand* in 2020 from a year earlier is almost unfathomable as well as unconscionable.

The scourge of gun deaths of young people absolutely warrants a full-court press from U.S. media and health officials and providers. But that’s no less true for motor vehicles, considering that cars and other motorized traffic are still far and away the biggest killer of U.S. kids — "kids" as society has traditionally defined them: persons younger than the teenage years.

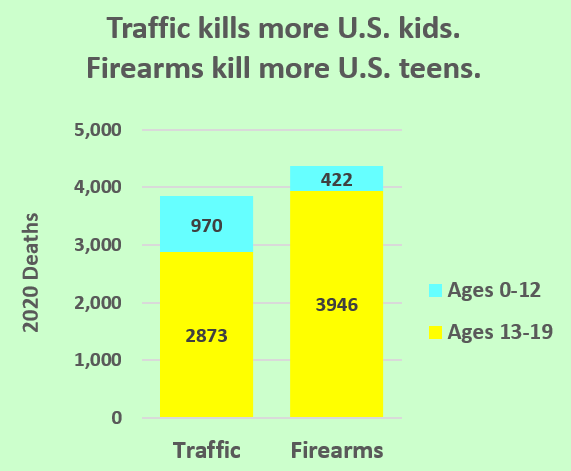

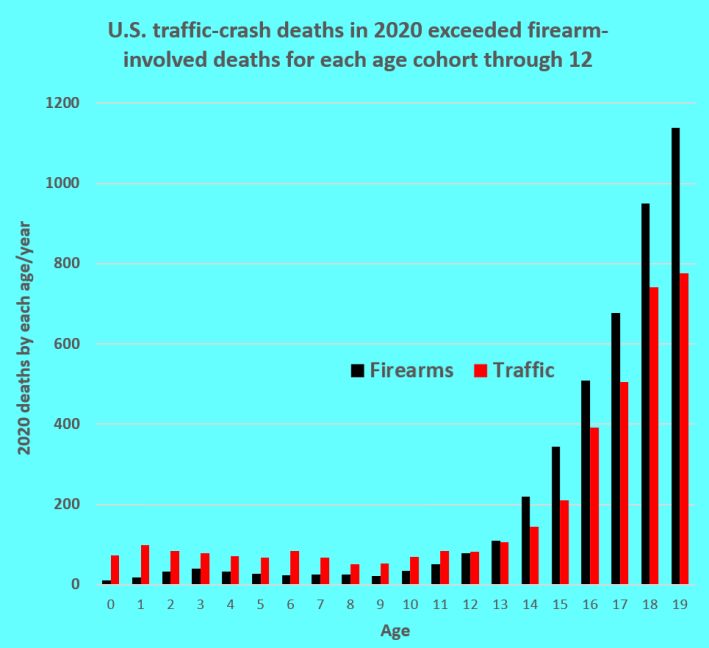

The first bar graph shows that in 2020, for each individual age “cohort” through age 12, U.S. deaths from traffic crashes exceeded deaths from firearm deaths.

Through age 12, more than 500 more U.S. kids died in vehicle crashes in 2020 than were killed with firearms. But the numbers flip beginning with age 13, and emphatically. For ages 13 through 19, firearms killed more than 1,000 more teens than did traffic crashes. (See chart below right.)

As a result, total gun deaths for the 0-19 cohort were, indeed, the greater of the two. That’s the finding the N.I.H. reported this summer, yet mistakenly labeled as "childhood deaths," a framing that Northwell, the Times and the New Yorker amplified this month.

As it happens, the age 12-13 break point between the primacy of traffic deaths and the primacy of gun deaths coincides with customary notions of childhood and adolescence. That custom resides in both language (“13” being the first “teenage” year) and biology, and is rooted in scientific discourse.

The U of M letter cited earlier, for example, is structured around that very distinction, as can be seen in its title, “Current Causes of Death in Children and Adolescents in the United States.” The American Psychological Association’s dictionary similarly defines childhood as “the period between the end of infancy (about 2 years of age) and the onset of puberty, marking the beginning of adolescence (10–12 years of age).”

A subsidiary APA definition even cuts off childhood much earlier, after age 7. And just last week, a New York Times story on the sharp rise in homicides of young people in 2020, did get it right, with the headline, “Homicides of Children Soared in the Pandemic’s First Year” and the subhead, “Killings of children and teenagers under 18 increased sharply.” It affirmed the conception of children and teenagers as separate categories.

Is it “just semantics” to insist that in 2020 cars killed more kids in the U.S. even though guns killed more of our young people overall? No. Constructs shape perception, and perceptions influence policy responses and, through them, the world we inhabit.

Any young person’s death is an immense tragedy, reverberating through communities and afflicting generations. Joy and wonderment gone in a moment, promise glimpsed but forever unfulfilled. The devastation is compounded when the deaths are ostensibly accidental, but actually preventable, as we know from the order-of-magnitude excess of the U.S. firearm death rate of young people vs. other high-income countries and our two-fold or greater excess for traffic death rates.

Yes, children are uniquely vulnerable, but they are also talismanic in shaping public priorities. The current framing threatens to subordinate vehicle dangers to firearm dangers when in fact both dangers are out of control. A U.S. safety establishment that has almost never meaningfully addressed vehicle dangers for any segment of the population has no business marginalizing motor traffic’s menace to children or anyone else.

Data/methodology: I downloaded 2020 fatality figures via the Centers for Disease Control’s online database. Motor vehicle occupants, pedestrians and “pedalcyclists” are reported separately and had to be aggregated. For some age cohorts, pedestrian and especially cyclist fatality figures were too small (single-digit) and thus were “suppressed” in the data. I approximated them by calculating the “missing” deaths from the category total and distributing them by prorating the cohorts’ percentages of occupant deaths.

* The University of Michigan researchers’ letter identifies “children and adolescents” as “persons ... to 19 years of age." From the CDC’s search engine, I calculated 4,368 firearm-involved fatalities in 2020. Dividing by 1.295, the 2019 fatality figure would be 3,373, implying an increase of 995 fatalities from 2019 to 2020 (the most recent year with full data).