"Walk this way!" as Aerosmith might say.

The "Make Way for Lower Manhattan" pedestrianization plan for the Financial District — which would turn the streets below Chambers into "shared streets" prioritizing walkers and cyclists over motor vehicles — has the backing of the Financial District Neighborhood Association. The area's immediate past Council Member, Margaret Chin, set aside $500,000 to complete the preliminary work on the plan, which was published in 2019.

Yet the Department of Transportation is dawdling on its implementation.

What's the hold up?

The answer can be found in the "Make Way for Lower Manhattan" report (full disclosure: I worked on it), which ascertained that almost half of the vehicles stored on two important streets, Broad and Nassau, had government-issued placards.

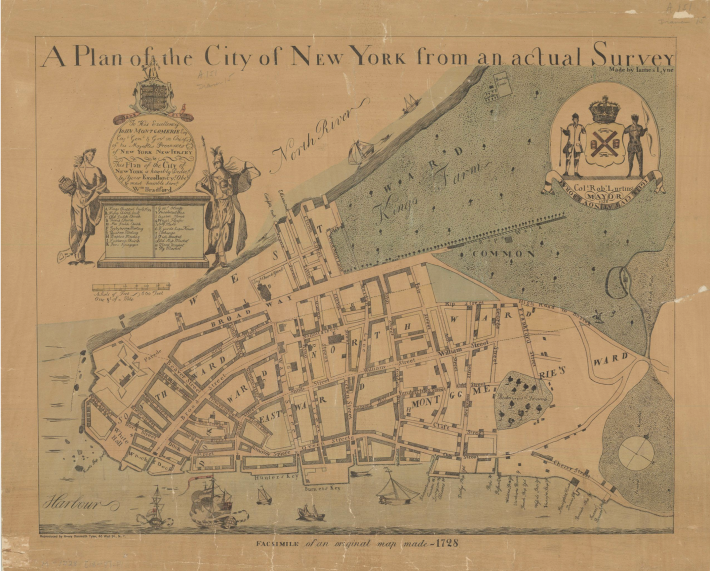

FiDi's streets — New York's oldest, the narrow, winding streets we inherited from the 17th century Dutch colony — are singularly ill-suited for the vehicle traffic we imposed upon them in the 20th century. But they also house the seat of city government — City Hall, the David Dinkins Municipal Building, and a raft of other agencies that occupy office space below Chambers. Many of the workers in those buildings have city cars.

Thus, the city's lack of action on the "Make Way for Lower Manhattan" baffles me as an urban planner — but makes perfect sense to me as a former city official who used to drive a city car with a placard. (I did not use the placard to beat any parking regulations, only to avoid feeding the meter.) Any pedestrianization plan worth its salt will curtail the space for government-subsidized "free" car storage (that is, on-street parking) — and that's anathema to the placard class!

Will we ever wrest the public’s streets away from the public servants?

That's up to our supposed "Get Stuff Done" Mayor, who hasn't evinced much concern about city cars, placards and their abuse.

Needless to say, the city should get right to pedestrianizing the area. If not now, when?

"Make Way for Lower Manhattan" is not the first time that the city has sought to pedestrianize FiDi. A 1966 plan called for more housing and for reserving Chambers, Fulton, Wall, and Broad/Nassau Streets for pedestrians. A 1997 pedestrianization study lamented the massive flows of black cars on FiDi's tiny streets. In 2010, under Mayor Bloomberg, the city succeeded in a small attempt at pedestrianization: the creation of the “shared street” in the area in front of the New York Stock Exchange. It's one of the city's most popular roadways for tourists and locals alike (as is the restaurant piazza on Stone Street nearby).

Of course, there are naysayers.

Those, like the Alliance for Downtown New York's Jessica Lappin, are engaging in obfuscation when they argue against pedestrianizing Lower Manhattan because the irregular streets make deliveries difficult for businesses and residents. No, Lower Manhattan's streets are not a grid like the car sewers of Midtown. That's precisely why they should be pedestrianized.

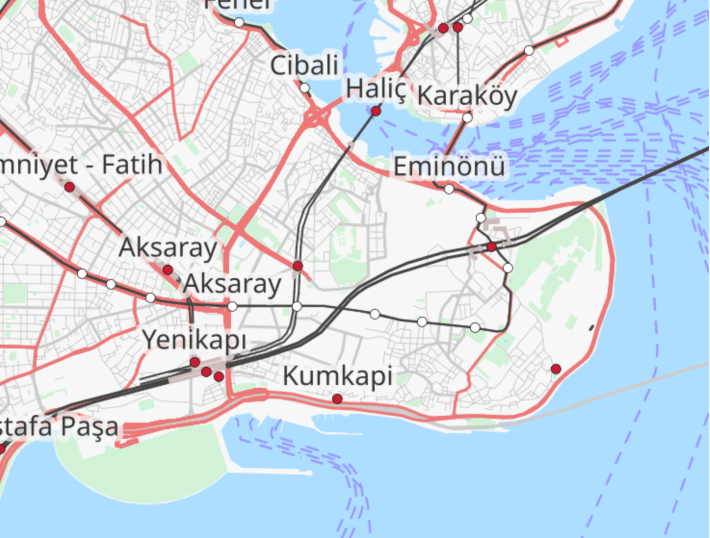

Lower Manhattan is a cul-de-sac on a peninsula; it naturally lacks thoroughfares, other than the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel. In that way, it resembles other cities situated on peninsulas, such as Dubrovnik, Istanbul, Montevideo, Mumbai, and Vancouver. In each of those cities, the municipality reserves the tip of the peninsula for plazas, points, and parks. So should ours.

Our "old city" has streets like other organic towns of its 17th century vintage, except by now they are filled in and densified beyond recognition. The 1728 map below shows the city we had then: a "high road" (Park Row, Centre Street and the Bowery) to Boston; Wall Street, which of course had a wall; a "rope walk" through the commons north of where City Hall is now; Dock Street, at actual docks, and no streets west of Broadway or east of Pearl (Queen) Street.

New York is a world city, and cities around the world have made their old cities car-free — to the betterment of their economies, environment and tourism. "Make Way for Lower Manhattan" makes way for people walking. Let's do it now.

Michael King (@TrafficCalmer), the DOT's first director of traffic calming, worked on the 1997 Lower Manhattan Pedestrianization Study and the 2019 "Make Way for Lower Manhattan" report.