The state legislature's decision to allow the city to operate speed cameras 24 hours a day, seven days a week was some classic Albany sausage-making that came after an over-reach by Mayor Adams and a strategic decision by two lawmakers to get what they could from their wavering colleagues as a deadline approached, according to interviews with lawmakers.

The result, though, is a watered-down bill that shelved tools to rein in reckless drivers that its sponsors Sen. Andrew Gounardes and Assembly Member Deborah Glick said would be transformative.

And with the pending renewal of the speed camera program this year, my bill would require the DMV to suspend registrations for all vehicles that receive more than 5 violations.

— Andrew Gounardes (@agounardes) February 8, 2022

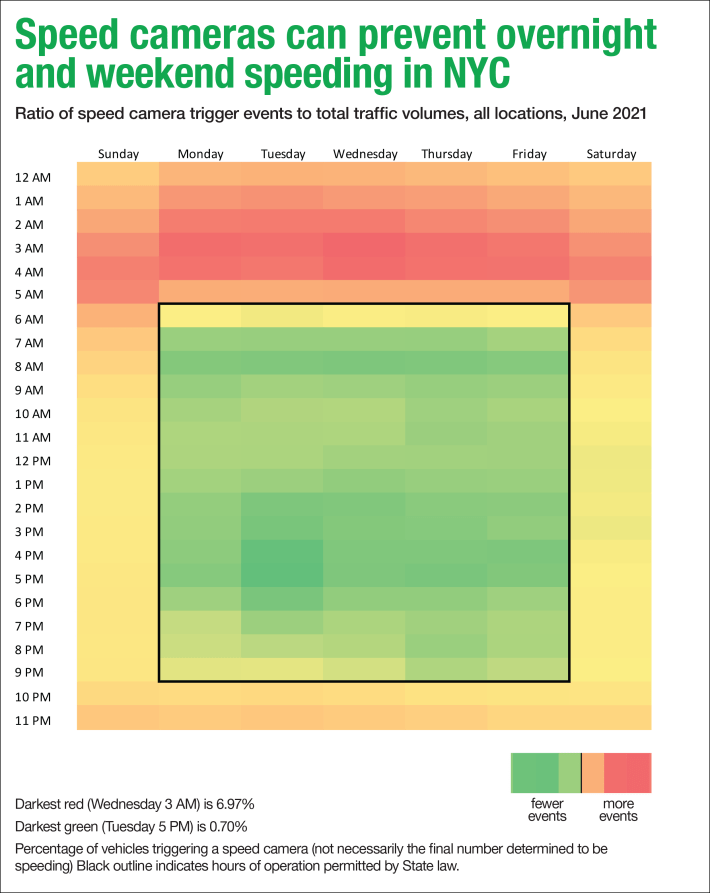

In the aftermath, there was plenty of blame to go around for the gutting of the bill — but very few people willing to air their gripes because of the historic nature of the resulting deal: For the first time since school-zone speed cameras were allowed by the state legislature in 2013, the cameras will be allowed to be on all day, every day, instead of just weekdays from 6 a.m. until 10 p.m. The Adams administration, like its predecessors, had long argued for full deployment of the life-saving cameras after statistics showed that more than half of the city road fatalities happen when the cameras are dark.

But Adams bears some of the blame for the failure of legislators to take up the bill's loftier provisions — which included an 11th-hour attempt to widen the radius around which cameras could be placed in school zones, which wasn't even in the working bill.

Glick, who has been an early champion of speed cameras since their inception, was surprised by the late and disorganized City Hall effort, she told Streetsblog on Friday after Gounardes reached the deal in his chamber.

“The issue of lifting the radius wasn't in the bill," Glick said.

In 2019, Glick said, when lawmakers expanded speed cameras the last time, the reauthorization allowed the city to operate the cameras within a quarter-mile radius of schools, instead of merely one-quarter of a mile from the school building itself.

At the time, city officials told lawmakers that the cameras would cover most of the city.

"But they came back just this week to say, ‘Well we think that’s not 100 percent accurate. We think there are gaps,’" Glick said. "You can’t spring something like that at the 11th hour when we’re trying to move a very critical piece.”

Glick said the administration's position — coupled with "concerns in our house about some pieces of the bill" — forced her and other lawmakers to "make an assessment — what are your top priorities?"

For her and Gounardes, the top priority was extending the cameras to 24/7 operation.

"For both of us, for advocates, too, that was a top priority," Glick said. "I can’t speak to what the city’s top priority was."

Initially, of course, the Adams administration was hoping to win "home rule" — a legislative term for full control of the speed camera system. Every New York mayor — and a retinue of activists — has had to journey to Albany every few years to beg lawmakers for the reauthorization of the cameras, or mayoral control of the city school system, and this year, City Hall hoped to break that cycle of pain by arguing for full control.

Glick suggested that full "home rule" was a bridge too far.

"The larger question is whether the city’s focus on a very broad authority rather than specific important pieces was the best strategy," she said.

Her answer? It was not.

“The city had lots of press conferences on home rule and really didn't spend a lot of time in Albany,” she said. “I understand you want to build public support, but you can't do that solely; you have to engage with the people who are going to be voting on the matters you care about. Has to be both inside and outside. Conversations have been only within the last week."

Glick confirmed what previously unnamed sources had told the Post and Daily News last week, that Adams's outreach was ultimately “dysfunctional” and that attempts by his team, including Department of Transportation Commissioner Ydanis Rodriguez, to get support from Albany were a “total fuck up.”

Nonetheless, once it became clear that full local control was off the table, Gounardes shifted his focus to ensuring that the legislature would pass his existing bill before the cameras shut off in July.

The bill went far beyond 24/7 speed cameras. How much further — simply compare Gounardes’s amended bill, S5602A, with the original bill that remains on the Senate website here. Gone are key safety provisions that would have fundamentally altered how reckless drivers are held accountable. The original bill would have:

- required the Department of Motor Vehicles to tell insurance companies whenever a car gets five school-zone speeding tickets in any two-year period

- suspended the registration, for 90 days, on any car slapped with six camera-issued tickets within two years

- allowed for escalating fines after a driver gets five tickets in two years.

- eliminated the provision in current law that prevents camera-issued speeding violations from becoming a part of a driver's record or used for insurance purposes.

Those provisions were never part of the Adams administration's push, several lawmakers told Streetsblog. As a result of being told repeatedly that the bill was designed to expand speed cameras to 24-hour operation, some lawmakers, even at least one of the co-sponsors, expressed surprise to Streetsblog about the other provisions. One, Sen. Roxanne Persaud, said she was didn't like having DMV report reckless driving to insurance companies. And Assembly Member Khaleel Anderson (D-Queens), who is a supporter of speed cameras and has been endorsed by StreetsPAC, questioned whether they were too punitive in general.

It's not clear when Gounardes and Glick started reducing the scope of their bill. By May 7, Gounardes was only still touting the escalating fines provision. The others seemed to have been gone by then:

The renewal of the speed camera program must at a minimum include:

— Andrew Gounardes (@agounardes) May 7, 2022

✅escalating penalties for recidivist reckless drivers

✅cameras operating 24/7 https://t.co/T8xVRk2g6C

Certainly, the arc of a bill from introduction to getting a governor's signature does not always bend to perfection; it’s not uncommon for amendments to be made to cut controversial elements in favor of the most important goal.

“You have to make decisions whether that provision is the hill you're gonna die on,” said Glick. For Glick and Gounardes keeping the cameras on 24/7 was that hill. As such, advocates and pols heralded the deal late last week, especially given how so many states don't even allow cities to operate speed cameras. But there's a big "but" after that.

“The importance of removing time-and-day limits from the city’s life-saving speed camera program can’t be overstated — the elimination of ‘cameras off, accelerators down’ periods overnight and on weekends is a very big deal — but it is painfully frustrating that the lawmaking process in Albany isn’t better, and that too many lawmakers continue to make excuses for drivers who seem completely unaccountable," said Eric McClure, executive director of StreetsPAC. "There’s a large cadre of recidivists who don’t seem fazed by racking up dozens upon dozens of speeding tickets, ... so maybe the way to get their attention is by levying geometrically increasing fines and taking away their keys. Thanks to another squandered opportunity, we’re not going to find out this year if that does in fact have an effect.

“We’re deeply grateful for the sponsors’ efforts to pass the full package, but Albany sadly remains a place where great ideas go to get kneecapped,” McClure added.

Mayor Adams wasn't having any of the naysaying, however accurate.

“Make no mistake about it, this is a major victory for New Yorkers that will save lives and help stem the tide of traffic violence that has taken too many," Hizzoner said in a statement.

And Transportation Alternatives, which has watched some of its key legislative priorities get left on the cutting room floor for several legislative sessions now, also championed the deal.

GOOD NEWS TO END THE WEEK:

— Transportation Alternatives (@TransAlt) May 20, 2022

Lawmakers in Albany heard your calls and announced a deal to *more than double* the reach of lifesaving speed cameras by reauthorizing the program and keeping them on 24/7.

This will be a significant step toward safe streets.https://t.co/V3o6M4ky7q

Neither City Hall nor the Department of Transportation would comment on the accusations of bungling the bill. Gounardes declined to comment until the bill passes.

— Additional reporting by Gersh Kuntzman