Brother, can you spare a billion dollars?

With just $1 billion, New York City could have free buses — a dream that was once again thrust into the ether after TWU Local 100 Vice-President JP Patafio suggested that free local buses were a better option than fare-beating enforcement, given that fare evasion on buses hit 29 percent at the end of 2021.

"They should look at making local bus service free," Patafio told the Post. "As we saw during the pandemic, it’s an essential public service — like, the most essential of the essential."

“I don’t know that there’s a police solution to 29 percent fare evasion. They should look at making local bus service free. As we saw during the pandemic, it’s an essential public service — like, the most essential of the essential.” - JP Patafiohttps://t.co/IH66srgovy

— Tri-State Transportation Campaign (@Tri_State) February 22, 2022

Patafio's remark came shortly after Boston Mayor Michelle Wu extended free fares to two more lines, turning Beantown from a place that once trapped Charlie on the MBTA into a place where Charlie could ride three bus lines for free. And all of Kansas City's buses are already as free as the wind blows.

Could such a thing work in New York? Got a billion dollars?

In 2019, the last normal year before the pandemic, the MTA collected $937.5 million in bus fares, an important consideration when comparing New York to places like Boston or Kansas City. In Kansas City, eliminating fares for the entire city's bus system cost about $8 million, which is only about 8 percent of the city's transit budget. Meanwhile, Boston is spending $4 million in federal fun bucks to run its three free bus line pilot.

But MTA officials are doubtful that one day they'll wake up with a big check with "FREE BUS SERVICE" written on the memo line

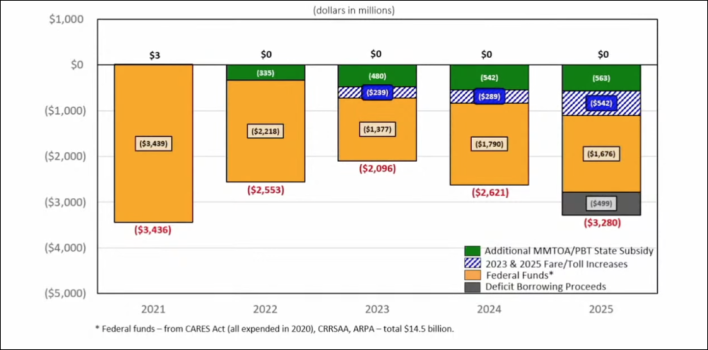

"We can all imagine that the proverbial pigs are going to fly, hypotheticals that are not going to happen," MTA Chairman and CEO Janno Lieber told Streetsblog on Tuesday. "Nobody's offering me a billion dollars for something other than closing the MTA's $2B-plus fiscal cliff."

Lieber is of course no stranger to appealing for transit funding by calling the subways and buses an essential service, but his rhetoric has been more in service of trying to keep the lights on at the pandemic-battered transit agency. Federal aid is currently buoying the MTA, papering over huge deficits from 2022 to 2025. When (if?) we reach 2025, the MTA is facing a $1.3-billion void, so when it comes to money and the MTA, Lieber suggested a full court press on filling the fiscal hole.

"We really need to focus," he said. "Anyone who's a supporter of transit and transit equity, we all need to focus on making sure the fiscal cliff gets dealt with."

One legislator, though, said free bus service advocates should be pressing their case right now.

"There's always going to be a looming budget crisis," said Assembly Member Jessica González-Rojas, a Queens Democrat who's spoken up for free transit before. "I don't want to make light of the many realities that system is facing. But how do we explore new, good ideas and take them seriously?"

González-Rojas is working on efforts to fill the MTA's hole, including pushing for a proposal to change the gas tax allocation in the state so that the MTA gets two-thirds of the revenue instead of just one-third, a move worth $500 million per year. She pointed to the MTA's own experiment with free buses during the pandemic as something the agency should learn from and possibly implement as a pilot on some lines sooner rather than later.

"It was such an effective tool during the pandemic, and it quickened the pace of the bus service. It was such a important public service during that time, and I really believe we should take a good hard look at it and, and allocate the resources to this effort," she said.

The MTA's decision to run free buses for a piece of 2020 was driven by safety concerns for bus drivers, who had less contact with riders who boarded through the back door. During the free fare stretch from March through August 2020, bus ridership actually outpaced subway ridership, which is extremely rare. And bus speeds rose (though that was more likely due to steep reductions in car traffic than reduced dwell time at stops as people fumbled for change).

Bus ridership, like subway ridership, hasn't returned to pre-pandemic ridership, hovering between 55 and 70 percent of 2019 ridership depending on the day. But even though bus ridership initially dropped after fares were brought back in September 2020, ridership has regularly matched and exceeded ridership in the free bus era, suggesting that fares aren't the driving force keeping people off the bus.

But bus ridership in New York has been suffering for years. Annual ridership dropped from 2.5 million riders in 2014 to just 2.1 million riders in 2019, and bus service, to use a highly technical urban planning term, sucked during the de Blasio era. The former mayor left office with buses moving an average of just 8.1 miles per hour, which was slower than the also unacceptably slow 8.2 miles per hour they were moving in January 2015.

To that end, Lieber suggested that better bus service was more important right now than the question of whether it should be cost something. Rather than free bus fares, the MTA boss said that riders would be better served by ramping up camera enforcement against bus lane blockers and by Mayor Adams's efforts to install 150 miles of bus lanes across the city.

"Buses are the top of the list for the MTA's transit equity agenda, and the first step is we must make the buses faster. If it's not faster than walking, it's not mass transit," Lieber said.

Tri-State Transportation Campaign Policy and Communications Manager Liam Blank agreed with Patafio that there were better ideas for the MTA than counting on police to recover every quarter lost to fare evasion on local buses, including bringing the long-delayed back-door boarding to buses, which advocates point out has shaved 40 percent off of dwell time (the amount of time buses remain standing still at stops) on SBS routes with all-door boarding.

"The MTA could add more SBS treatments to more routes, and tackle the issue that way. It's not free, but it's a using an honor system, and it has a lot of treatments that are needed for improving service like all-door boarding," said Blank, whose organization will be part of a rally for that better bus service next week in Brooklyn.

For her part, González-Rojas said there's no reason why the MTA can't walk (i.e. run the transit system) and chew gum (i.e. plan for a more hopeful future) at the same time.

"While we're addressing the immediate needs of improved bus reliability and service, it's not one or the other. I think it's a 'both and,' and I think we can continue to figure out ways to get to a free fare," she said.