Meet the new plan. Same as the old plan!

Upper West Side cycling advocates are appealing to Mayor Adams to take a fresh look at a $150-million road-rehab project after the Department of Transportation declined to make safety changes demanded by the community.

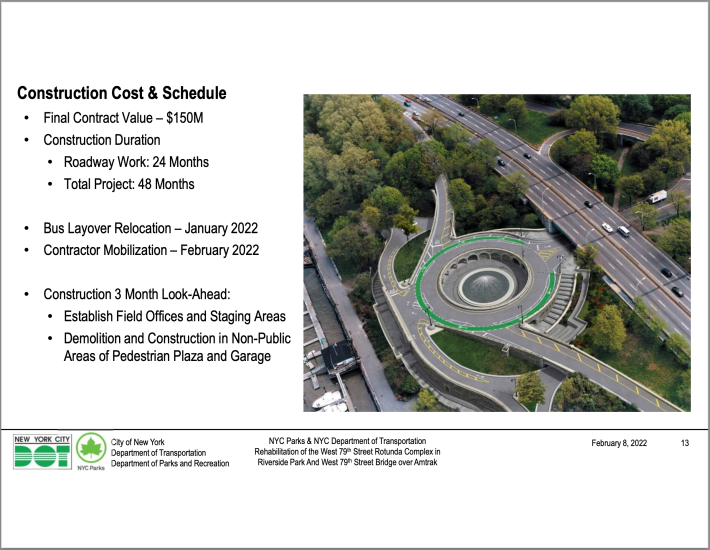

The project — the renovation of the traffic circle atop the 79th Street Rotunda, a decaying Robert Moses-built edifice which acts both as an exit of the Henry Hudson Parkway and a well-used entrance to Riverside Park — for several years has been a flashpoint for activists.

The traffic circle — a narrow roundabout with no shoulders, like other Moses roadways such as the Brooklyn-Queens and Cross Bronx expressways — originally served only as a grand entrance to the Upper West Side for the hundreds of car drivers exiting daily from the parkway. In recent decades, however, the circle has become the gateway for cyclists seeking access to the nation’s busiest bike path, the Hudson River Greenway. The two groups of users mix dangerously in its narrow bowl.

In 2019, Manhattan Community Board 7 unanimously disapproved the project absent safety improvements, including a protected bike lane; better signage, including "flashing warning lights"; and tactile warning treatments, such as rumble strips on the motorist approaches to the traffic circle.

On Tuesday, however, a DOT rep presented the latest iteration of the project to the CB7's Transportation Committee, and it contained none of the resolution's recommendations — only a painted bike lane with a slight curve where the exit ramp meets the traffic circle to slow motorists, according to several who heard the presentation. The DOT presentation itself, obtained by Streetsblog, contains no verbiage describing its plans for the bike facility — only a photo suggesting that arrangement, below.

Carl Mahaney, an architect and organizer for StreetopiaUWS, a sister organization of Streetsblog, said the fact that the DOT presented the same dangerous design after CB7 passed a unanimous resolution requesting safety changes is "a damning indictment of the city's priorities."

The Rotunda project, he said, "should have been an opportunity to radically rethink the use of that structure to bring it in line with the city's stated transportation, equity, and climate goals," but the design that the DOT presented locks in auto-centric infrastructure and funnels hundreds cars a day into the neighborhood instead of "offering a generous, green pedestrian and cycling gateway connecting the community to the waterfront."

Mahaney appealed to the new administration's sense of equity in pressing his case.

"Mayor Adams needs to think more creatively about how we spend our limited transportation and infrastructure dollars and consider who benefits from these projects and who is harmed," he said.

Ken Coughlin, a CB7 board member who saw the Rotunda presentation, said he was "shocked and disappointed that DOT adopted none of the safety measures to protect cyclists in the traffic circle that we called for in our resolution, and that they couldn't really explain what other concerns outweighed the lives of cyclists. They said they'd continue to consider our advice but couldn't adequately explain why they'd rejected it."

A silver lining, Coughlin said, it that "we have a couple of years — these treatments can wait until the end of construction and the roadbed is repaved," so the new administration has time to fix the mistakes of the last one.

The DOT, however, is sticking to its guns.

“The DOT has reviewed the 79th Street rotunda options very closely and adjusted our proposal to reflect the community concerns while also proceeding with this critical structural repair project," said spokesman Tomas Garita. "We believe this design will be safe, and will continue to work with the community on how to best upgrade bicycle infrastructure in the area.”