No more free lunch!

At an epic, hours-long City Council hearing on Tuesday one key element emerged for the plan for converting the pandemic-era Open Restaurant program into a permanent one in 2023: restaurateurs will have to pay to use the public roadway space along the city's extremely valuable, but often given-away, curbside.

And that could lead, activists hope, for reform of the singular giveaway of public space in city history: the surrender of the curbside lane on virtually every street to car owners for free.

3 @FDNY Trucks cannot get though East 11th Street because of ONE double parked vehicle. For 10 minutes. Abolish free car parking: heal the city. pic.twitter.com/H4vvj9vTJF

— Choresh Wald (@Choresh2) February 9, 2022

The Open Restaurant fee "will be based on the location of the restaurant and the size of the space the restaurant will be using for its sidewalk or roadway café," Transportation Commissioner Ydanis Rodriguez told Council members on Tuesday. For now, it's unclear how much the curb space fee will be, above the initial $1,050 license fee for a sidewalk or roadway café (renewable for $525). Those fees are up slightly from the old sidewalk cafe program, which ended with the pandemic and was ostensibly folded into Open Restaurants, which will function as the only program going forward.

The fees cheered livable streets activists, such as Sara Lind, the policy director of Open Plans (a sister organization of Streetsblog), who testified that a fee "that goes toward the management of the public realm is a reasonable requirement" for use of curbside space. But she also noted that other curbside users — such as the motorists who use the city's copious free parking for private car storage — also need to pay their fair share for space, too.

In its testimony, Transportation Alternatives also focused on the millions of free "parking spaces" in the city.

"The current allocation of curb space in our city is highly inequitable," said the group's deputy director Marco Conner DiAquoi. "Seventy-five percent of our public curb space is devoted to the movement and storage of vehicles. New York City has three million free parking spaces, mainly for personal cars — private property stored for free on public space. When just 0.2 percent of these spaces were put to higher use for outdoor dining during the COVID pandemic, New York City saved 100,000 jobs.

"We believe in a city and future that puts our shared public curbs to better use than the free storage of private vehicles," he added.

Oddly, the Department of Transportation, which will take over the entire outdoor dining program from the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection, could not say how many of the estimated 12,000 Covid-era outdoor dining "sheds" are in metered parking zones or along side streets or avenues that do not have meters. In any event, it is likely that restaurants will generate considerably more money for the city in fees and sales taxes per "parking space" than the current use of car storage.

The long (eight-and-a-half-hour!) hearing was actually a debate on two matters: the Open Restaurants Zoning Text Amendment, which the Planning Commission passed last year in order to legalize outdoor dining in areas of the city, mostly residential, where al fresco eating had been prohibited; and legislation to put all outdoor dining in the DOT portfolio.

As such, much of the debate focused on how the city will implement a permanent program, setting aside the question of whether it should or should not. Rodriguez, who was on the other side of the Council grilling for the first time as commissioner after 12 years in the city's legislature, promised a "simpler process" for the licensing outdoor-dining spaces, which many at the hearing faulted as costly and excessively bureaucratic in the pre-Covid days, when every community board in town got to vote on every single outdoor cafe. (There will still be community "review," Rodriguez said.)

Above all, the hearing demonstrated the need for a single agency to focus solely on public space management, even if Council members and some activists didn't actually call it that. Many speakers, for example, clearly didn't trust the DOT or think that it works well with other agencies — including the NYPD, Health, and Sanitation — in managing the program, which has been dogged by complaints of vermin, dilapidated sheds or unused space.

Council Member Julie Menin (D-Upper East Side) — a former Consumer Affairs commissioner — suggested that the program might require an inter-agency "task force."

Her colleague, Christopher Marte (D-Lower Manhattan), complained not only of a high concentration of restaurants on narrow streets, but other problems common in restaurant-rich areas: noise, rats, garbage, crime, and a circus atmosphere that happens when a great number of people congregate outdoors. Those — and the loss of parking — were the issues that a number of West Village residents cited last year when they sued the city to end the Open Restaurant program. The suit is ongoing, but the city says it is confident that it will prevail on the merits.

In any event, Marte, Menin and even the plaintiffs in that case are all, in their own way, calling for better management of public space.

And, of course, so are activists.

"We call on the city to create a framework and structure for better coordination, stewardship, and management of public space, including the Open Restaurants program," testified Jackson Chabot, Open Plans's director of public space advocacy. "Formally, we call for an Office of Public Space Management."

Conner DiAquoi agreed.

"Once permanent rules are set for the Open Restaurants program, we need to continue reimagining the entire streetscape," he said. "When streets are planned around people, there is plenty of space for parklets, bike lanes, benches, bike share, and outdoor dining. Everyone can be included on and benefit from our streets if we stop planning around the needs of cars and start planning for people."

The hearing was the latest step in a process that began in March, 2020, with the immediate closure of city restaurants at the beginning of the lockdown. Within months, however, the city created a pilot "Open Restaurants" program that allowed eateries to take curbside and other public space for commercial purposes, replacing, in most cases, free car storage. The program — which even its detractors acknowledge staved off the pandemic-induced collapse of the restaurant industry — has proved to be one of the most popular recent additions to New York's streetscape, according to surveys. More than 12,000 restaurants have participated, thereby saving some 100,000 industry jobs, according to city estimates.

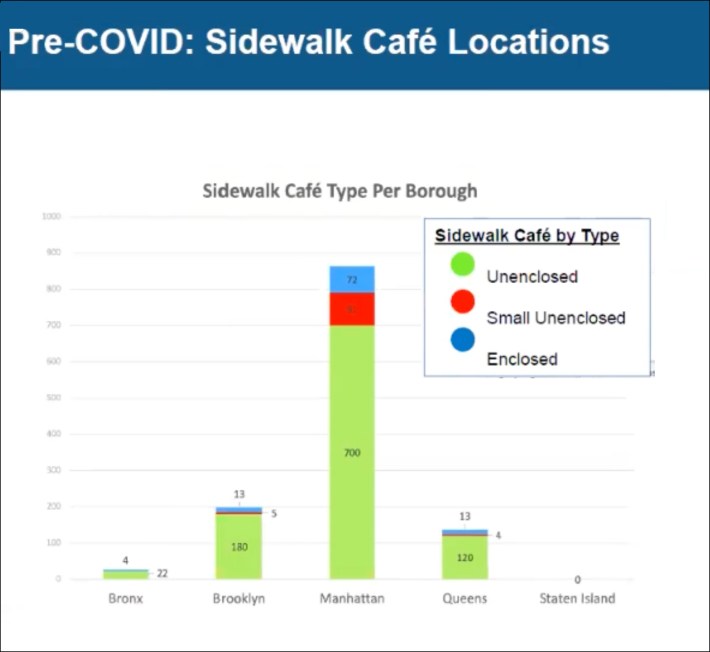

The program, moreover, created a café scene in many outer borough neighborhoods where there was none; for example, The Bronx had a mere 26 restaurants with outdoor seating before Covid, while now it has 659. Queens went from 137 to 2,400. Rodriguez painted the development as a great democratization of city life that had given outdoor-dining options to many immigrant areas and "will particularly help businesses in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color."

Now, to make the program "permanent," the city must codify its rules. To do so, the DOT first reached out to 59 community boards and five borough boards for advice and consent — which was not easily obtained. About 30 community boards rejected the city’s proposal; about 22 supported it or at least did not oppose it. Some boards objected to nightlife spilling into the street; some said the restaurant "sheds" led to garbage problems; and at least one CB was most offended to lose its role in overseeing which local eateries get sidewalk cafes. [To read the zoning proposal and the various recommendations from earlier in this process, click here to download the City Planning Commission’s report.]