A quiet revolution in public space management is spreading throughout New York City — and it is not being undertaken by the city bureaucrats who are paid to oversee our streetscape, but by Business Improvement Districts, private entities that raise money from commercial interests and also raise questions about the future of urban space.

But if a bevy of recent pedestrianization initiatives is any indication, if a neighborhood wants extensive street improvements, it had better have a BID, as the city Department of Transportation has left major decisions about planning and design of key areas of the city to these private business organizations, the majority of which operate in rich, White areas.

BIDs have long spearheaded pedestrianization efforts — such as in the Financial District (2003), Madison Square (2008), Herald Square (2009), and Times Square (2012-16) — but in the last nine months, these efforts have accelerated, with the BIDs of the Meatpacking District, SoHo, Hudson Square, Union Square, and the Downtown Brooklyn all announcing far-reaching plans to create pedestrian-friendly areas.

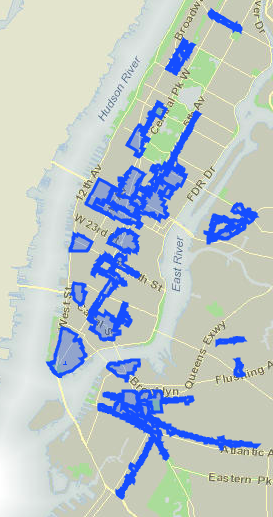

BIDs comprise a tiny part of New York City’s footprint — they cover only 2 percent of the area of the five boroughs — but they have become engines for livable-streets innovation. The BIDs, which are technically “public-private partnerships” with the DOT, steadily have transformed major shopping and commercial districts in the densest parts of the city into some of the most people-friendly streetscapes in Gotham.

Business Improvement Districts don’t undertake such efforts simply out of civic-mindedness and enlightened urbanism — although many of their members and managers profess such — but rather because shoppers, diners and strollers are more likely to spend money on people-centered streets.

Pedestrianization is “good for business and good for our neighborhoods, because people want to be in them. We’re bullish,” said James Mettham, executive director of the Flatiron/23rd Street Partnership, which just worked with the DOT on the city’s longest shared-street block, on Broadway between 21st and 23rd streets. The shared street is a key part of the city’s “Broadway Vision” for a pedestrian-friendly corridor between Columbus Circle and Union Square — a civic vision, perhaps, but one that is anchored and maintained entirely by BIDs.

Upcoming innovations

As the pandemic recedes, BIDs are moving more aggressively than city officials in advocating for, and creating, more pedestrianization — seeing the “open streets” movement pioneered by street-safety activists as the harbinger of things to come and using the coming post-COVID moment as an opportunity (or the excuse) to extend their reach and pedestrianize miles of New York.

Consider the following:

- The Hudson Square BID, which covers the old Printing District above Canal and below Greenwich Village on the West Side, announced last month that it is spending $22 million to create pedestrian-friendly corridors along Houston, Washington, and Greenwich streets and better connect the area to Hudson River Park (see photo at the top of this story). The plan will create two miles of protected bike lanes and claim 50,000 square feet of curbside space for uses other than parking. The BID already spent $27 million in recent years in order to widen sidewalks, plant 350 trees, and improve local parks.

- The Union Square Partnership in January unveiled plans to add 33 percent more public space to the square by banishing cars from some streets and connecting some marooned triangles of land to the park. In particular, Union Square West, made car-free some time ago, will get an even stronger connection to Broadway via improvements to the 17th Street plaza. The $100-million plan would add 100,000 square feet of public space by subtracting room for cars.

- The Meatpacking District’s BID is using Little West 12th Street, an open street, as a laboratory for street innovation. In August, the DOT and the BID made Gansevoort Street, Little West 12th Street, and West 13th Street permanently car-free between Ninth Avenue and Washington Street, using movable planters and street furniture. The streets of the formerly industrial area themselves are now paved with what they were historically — cobblestones.

- The Flatiron/23rd Street Partnership, as mentioned above, partnered with the DOT on the longest shared stretch of Broadway. It also just hosted a month-long “pop-up” plaza on Broadway just north of Madison Square Park, an experiment that could presage a more permanent installation.

- The Lower East Side Partnership, a BID that operates in a narrow swath of the central shopping district of the old Jewish neighborhood, is one-upping the city on garbage. It recently proposed to its community board that the BID centralize commercial trash collection and even bring in compact street sweepers in order to help deal with local trash issues. (The city won’t fund such sweepers.) The BID is pressing the board and the Department of Sanitation to bring the “Clean Curbs” pilot containerization program to the LES — months before the city has gotten the program off the ground.

- The SoHo-Broadway Partnership recently unveiled a “vision plan” for making parts of Broadway, Prince and Broome streets more pedestrian friendly, in order to promote safety, rationalize operations such as garbage collection and loading, better the environment and create more space for cultural events and people in a district, that hadn’t seen real any street improvements for a half-century. The BID piloted “Little Prince Plaza” on successive Saturdays in October (see Streetfilm below).

- The Downtown Brooklyn Partnership, a consortium of three BIDs covering the Fulton Mall, the Borough Hall area, and the Metrotech Center, recently introduced a “Public Realm Action Plan” to pedestrianize and green a large swath of the area under its purview, including some smaller side streets. The BID worked with design firms Bjarke Ingels Group and WXY architecture + urban design not only on shopper-friendly street treatments, but on “green infrastructure” to improve air quality and mitigate heat-island effects.

These “vision plans” are variations on car-free districts pioneered during the last half-century in Europe and tacitly acknowledge the simple fact that cars ruin cities. Meanwhile, the DOT — which traditionally has been dominated by a cadre of traffic engineers — remains beholden to political pressures from car-owners entrenched at community boards (indeed, the DOT’s mission statement is long on “the movement of people and goods in the City of New York” and very short on creating great public space).

In fact, opposition to BID pedestrianization efforts often organizes around community-board meetings, such as at a Nov. 4 meeting of the Manhattan Community Board 2 Transportation Committee at which the SoHo-Broadway BID presented its vision plan; for a contentious four hours, resident after resident rose to defend the needs of motorists, even as many complained of hellacious traffic congestion, pollution, and ear-splitting noise from cars.

But BIDs know better.

“We want an improved quality of life throughout the Brooklyn core,” Downtown Brooklyn Partnership President Regina Myer told Streetsblog. “We want to push forward in places that have been ignored. The city hasn’t taken a hard look at the streets other than the arterials, like Atlantic Avenue. All of those streets are home to tens of thousands of people.”

Why is this happening?

The rise of the BIDs stems from something rotten in the Big Apple: public disinvestment. The movement to form BIDs started about 50 years ago with the deterioration of city services and accelerated during the city’s late-1970s fiscal crisis; the city enacted legislation authorizing BIDs in the early 1980s. The first BID, the Union Square Partnership, formed in 1984 with a heavy assist from Con Edison. After that, the BIDs, loosely overseen by the city’s Department of Small Business Services, took off like a shot.

According to the city’s Fiscal Year 2020 BIDs Trends Report, the most recent one available, 76 BIDs served 93,000 businesses and collectively spent $170 million on supplemental services in that year, the largest chunk of which (25.5 percent) was on sanitation followed by marketing and public events (20.1 percent) and public safety (14.6 percent). They spent about $17.1 million on streetscape and capital improvements in the teeth of the pandemic. If you subtract marketing and public events costs, BIDs collectively spend almost $136 million to supplement services that the city supplies to all areas.

BIDs employed 435 full-time staffers in FY 2020 and tens of thousands more part-time. Almost two-thirds of the BIDs are found in Manhattan (25) and Brooklyn (23). BIDs manage 12 percent of the open streets in the city’s program and have been heavily involved in the “Open Restaurants” program. A glance at any BID’s website, almost all of which feature cheery photos of local cafes, demonstrates how the needs of the restaurant industry drive a good deal of BID activism on behalf of people-centered streets.

The downside

But when the impetus for people-centered street innovation comes mostly from commercial interests, it demonstrates by its very existence the atrophy of those functions in the public sector. It also has profound effects on equity when areas — especially poor neighborhoods where, not coincidentally, streets are the most dangerous — don’t have BIDs: They simply don’t get the amenities that other areas enjoy. The growing privatization of public space management — and the private security services that come with it — also creates opportunities for harassment of people of color, youth, and the homeless.

And if a BID doesn’t adopt a street, it’s up to the DOT to fix it — a scenario with predictable results. Manhattan’s gritty Canal Street, for example, is not currently part of any BIDs streetscape plan, so it remains a dangerous car sewer to which the DOT is only making marginal changes.

“Why is it that wealthy BIDs are leading the way on pedestrian safety?” asked Jackson Chabot, director of public space advocacy for Open Plans, the parent company of Streetsblog, in City Council testimony on Oct. 25. “I wish that the Department of Transportation had the same transformative vision for our streets and sidewalks. … New Yorkers deserve access to safe public space, literally outside of their door. Open streets have shown us this is possible; now we need a framework for public-space management to manage them municipally.”

Others have an even more pointed critique of BIDs. Nicole Murray, a member of the Ecosocialist Working Group of NYC-Democratic Socialists of America, sees the BIDs as vehicles for small-business owners to impose their needs onto public space through direct government support and funding.

“The needs of the public may clash, directly or indirectly, with the spaces BIDs create,” she said. “While BIDs are often clean and well-lit, they are hostile to existing social and economic structures residents carve for themselves. Street/table vendors, skateboarders, dancers, game and social circles … become loiterers, nuisances, and vagrants. Anything that doesn’t improve the image of the district — and the businesses’ bottom lines — must be replaced with approved structures: hostile architecture, loud shopping music, security and surveillance.”

There is an inherent conflict between property-minded BID constituents and the itinerant city population. The dust-ups among BIDs and the homeless people moving through their territory led to a wholesale rebranding of BIDs’ efforts to remove folks as social-service outreach. Street vending has proved another flashpoint with bricks-and-mortar BID members, with store-owners complaining of unfair competition and peddlers citing official and police harassment.

Still, BIDs have an advantage over the DOT on street questions because of their small geographic focus, tight connections to property owners, businesses, and residents; and granular know-how on quality-of-life issues, which obviously affect an area’s commercial fortune. BIDs even have stepped into the breach on open streets — more than half of which failed because of of DOT neglect — by running 10 percent of the 274 open streets created during the pandemic, according to a Transportation Alternatives report.

“BIDs have more flexibility in contracting and procurement, are more nimble, and can be more responsive,” said Mike Lydon of Street Plans, a design firm that worked on the SoHo-Broadway vision plan and many other such efforts around the world.

“What you are witnessing is driven by real and perceived needs [in] making large gains in public space and livability at the global scale … as well as the moment we are in politically,” Lydon added. “With so many new Council members and a new mayoral administration, it just makes sense for BIDs to put their best foot forward to develop public-realm plans to help set the agenda for our city’s incoming leadership and to help businesses recover from the still ongoing economic impacts of the pandemic.”

As for the BIDs tendency to privatize, securitize and monetize public space, Lydon says, well, that is what Americans get for their low-tax philosophy. He said that “every plaza, park, and neighborhood should have stewardship resources,” but Americans don’t invest in the public realm.

“We don’t have a money problem; we have a political problem,” he added. “When I work with European colleagues they really struggle to understand why we have to tax ourselves at a district scale to avoid taxing ourselves at a citywide scale in order to deliver better public spaces but only in the places that can afford to tax themselves. … When you look at almost every single other modern nation, they do not have to invent the BID because the resources, as strained as they might be in some cases, do flow into local governments to support the public realm.”

The fix, he said, is to lay the groundwork for an Office of Public Space Management — a body either within the DOT or the Mayor’s Office that can provide the kind of attention to neighborhood placemaking that BIDs do in areas that don’t have BIDs. Open Plans has also advocated for such an office.

The DOT says that it is seeking to establish pedestrian areas in neighborhoods that lack BIDs and to bolster the resources for the now-permanent open streets program. Three major-league open streets — the “gold standard” 34th Avenue in Jackson Heights; Berry Street in Williamsburg; and Vanderbilt and Underhill avenues in Prospect Heights — will receive “Broadway Vision”-style pedestrian and bicycle improvements next year (though those plans are still heavily reliant on volunteer effort, which has left too many open streets reclaimed by cars, TA’s recent report showed). Of the 85 car-free plazas the department has created, 45 have non-BID stewards, including schools, businesses and not-for-profit groups such as the Youth Ministries for Peace, its partner for the Morris Avenue Plaza in the Soundview section of The Bronx. The city cited two programs, OneNYC Plaza Equity and Public Space Activations, that aim to give local groups in strapped areas with funds, technical assistance and programming for pedestrian spaces.

“Every New Yorker deserves safe and accessible public spaces where they can relax, meet with others, or enjoy art and entertainment,” said department spokesman Vin Barone. “Equity is a guiding principle as we create new pedestrian spaces and plazas citywide. In addition, as we finalize rules for a permanent open streets program, we will bring open streets to more neighborhoods — even those without strong community resources.” (This is almost exactly what then-DOT Commissioner Polly Trottenberg said at the launch of open streets in May, 2020.)

Local community groups often lack the know-how or the personnel to manage public spaces successfully on their own. Public-space management is a profession, involving expertise in disciplines including procurement, contracting, event-planning, sanitation management, vendor relations, street design and maintenance and others.

Like Lydon, several BID leaders interviewed for this story support the idea of making public-space management a singular focus for the city, although they declined to endorse any one plan for such an agency. Mettham said that having a deputy mayor for public space as the “connective tissue” among the “alphabet soup” of city agencies would be helpful in solving jurisdictional questions.

What’s needed is “change management,” said David Estrada, the executive director of the Sunset Park (Brooklyn) BID and a co-chair of the NYC BID Association. Unfortunately, the responsibility for public space is so “siloed across agencies.”

“BIDs have taken responsibility for handling a bureaucratic process that is difficult to navigate,” he said, but often “they are being left to hold the bag and clean up the mess.”

As the city emerges from Covid-19, it may be time that residents who don’t have the luxury of living in the confines of a BID get some help with those same matters.