They built it — and they came.

The year-old Crescent Street protected bike lane, a two-way, 1.8-mile route connecting the Triboro and Queensboro bridge in Astoria, has been mobbed with riders since it debuted last October, according to data collected by a local activist.

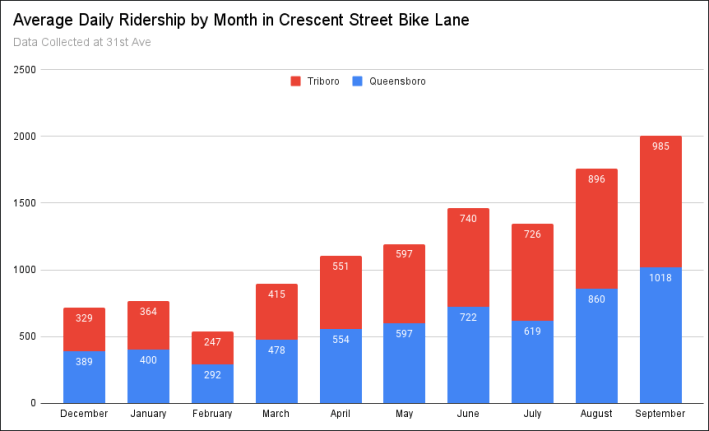

About two cyclists on average pedaled past a counter placed along the crucial north-south route every minute — with the one-day record of 2,300 trips set on a day in September, said Macartney Morris, who set up a camera to count the bikers last December.

The results show that the citywide bike boom that began last year has only grown in the places where the Department of Transportation has established life-saving infrastructure. It also puts to lie the naysayers who opposed the bike lane, claiming that industrial areas such as those surrounding Crescent Street would not draw a sufficient numbers of cyclists. Indeed, in 2019, local Assembly Member Cathy Nolan outrageously suggested that biking should be banned on Crescent Street and similar roads because of truck traffic in the area.

Last November, only a month after the bike lane was installed, the driver of a massive beer-distribution truck fatally struck 35-year-old scooter rider Alfredo Cabrera Liconia on Crescent Street near Astoria Boulevard. But despite the sharp spike in the number of bikers, the number of crashes has fallen, showing the safety effect of the lane, according to data from the city compiled on Crash Mapper.

Before the installation of the protected bike lane, from June to October 2019, 67 crashes occurred on the street, causing 13 injuries, including to three cyclists and one pedestrian. In 2020, during the same four-month period, there were 27 crashes — a 60-percent drop — causing five total injuries. And this year, from June to October, there were 26 total crashes, causing 10 injuries, including to four cyclists and three pedestrians, according to the data. The city had installed a temporary bike lane in May 2020.

Morris said he and his husband first set up a camera outside their home on Crescent Street near 31st Avenue last December, collecting about a year's worth of data using a software program, Camlytics, which uploaded the number of bikers who traversed the protected bike lane in each direction onto a spreadsheet. The results showed exactly what bike advocates had hoped: More people will choose to bike if given a safe route.

“I spent quite a few years advocating for what I thought would be successful, but the actual success has far exceeded what I imagined,” said Morris.

Even during the winter, in conditions of rain, sleet, and snow — often when many delivery workers are the only ones on the road — an average of 600 bike trips were taken on Crescent Street. The number tripled this past summer, when an average of almost 1,000 trips occurred in each direction in September.

“Every month since it’s been implemented we continue to see sustained growth," said Transportation Alternatives organizer and activist Juan Restrepo. "More people are learning about Crescent Street. Many people are getting into biking in Astoria or exploring new parts, and finding new routes to Manhattan."

Morris spotlighted one day in October in order to show just how many people are relying on the safe route. During rush hour on Thursday, Oct. 14, from 6:26 to 6:41 p.m., Morris said he counted 74 bikes and scooters, two people jogging, 80 pedestrians, and 131 cars — a ratio of 131 motor vehicles to 156 sustainable transportation modes.

“Take a moment to let that sink in: There were more people biking and walking on Crescent Street than there were cars and trucks driving,” he said.

The data should be a wake-up call for the DOT, Morris said — proving that cyclists desperately need more safe routes, and especially a new east-west route to create a connective, accessible network across Queens.

“What’s so frustrating is that since the Crescent Street bike lane, which is such a huge amazing success, DOT has been MIA in northwestern Queens. The fact that they haven’t led with it for a second north-south or east-west route in Astoria is just criminal,” he said.

Morris’s data comes just days after the DOT reported that bike lanes, both those that are protected in some fashion and those that are simply painted, lessen the risk of cyclists becoming injured by 32 to 34 percent, respectively. But advocates criticized the report, arguing that the relatively small difference actually represents more than just numbers, because protected lanes help riders feel safe. Earlier DOT studies have showed that protected bike lanes have the support of 68 percent of voters (including majorities in all boroughs), and help close the gender gap in cycling by making female bikers feel safer on roads.

A spokesperson for DOT told Streetsblog that the city is working to expand the bike network in Astoria.

"We are actively working to further develop the Astoria bike lane network with both protected and conventional lanes with north-south and east-west connections. We are closely consulting with the community and stakeholders as these plans progress. We will have more details to release next year," said Seth Stein.