Locals living in a wealthy Rockaway Beach enclave are fighting to stop the feds from installing accessible walkways and a concrete path along the public beach that has ostensibly become their private oasis.

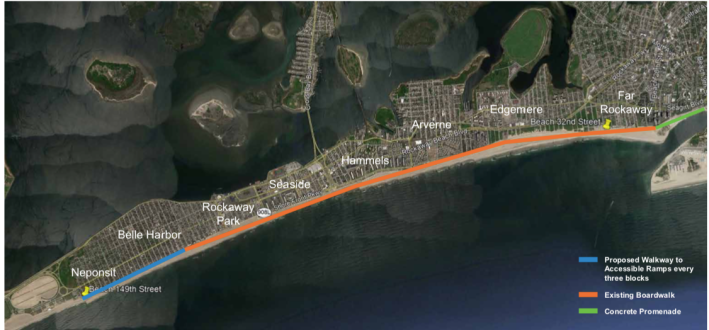

The improvements are part of a $250 million federal resiliency project to shore up six miles of receding coastline after Superstorm Sandy severely damaged the peninsula in 2012. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers plans to reinforce the dunes, install dune crossovers, and replenish the depleted sand, as well as extend the Rockaway Beach boardwalk from where it ends now, at 126th Street, through 149th Street, by building a new five-foot-wide concrete walkway.

But the pedestrian-infrastructure project is facing serious opposition from residents of Neponsit and Belle Harbor, which are the last two residential communities on the Rockaway peninsula before it turns into the federally-managed Jacob Riis Park.

“I don’t want it. You see what happens down there? The boardwalk down there? The environment it brings?" said Andrew Patti, a member of the Belle Harbor Homeowners' Association, who was on the beach near 131st Street on Thursday afternoon. "For argument's sake, some of the people on there with their bikes are not respectful. They ride motorcycles on it; I don’t want that. I’d rather keep it like this, it keeps it semi-private.”

Patti added, “I just don’t see the necessity, we’ve never had it. I’ve been here 29 years, and put a lifetime into this already, and to see it destroyed because people want to walk along to see my house is not conducive to what I like. There's nothing here for them.”

According to the Rockaway Wave, 84 percent of more than 1,000 Belle Harbor residents surveyed said they were “completely opposed” to the construction of the walkways. Just over 4 percent of respondents said they want the walkways, according to the local paper.

The walkway would cross through the neighborhoods of Belle Harbor and Neponsit, where the average median household income is $108,289 — more than two times what it is in the rest of the communities that line the boardwalk. The path would feature four zig-zagging ramps, all compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act, to take beachgoers, including those with strollers and wheelchairs, down to the water. The ramps are required by the ADA and the Federal Government's Architectural Barriers Act.

Hank Iori, a former president of the Belle Harbor Homeowners Association, says his opposition to the walkway and ramps isn’t NIBMYism, and has nothing to do with maintaining the community's relatively private beach access. Iori claims the concrete walkway would be dangerous with sand blown onto it, causing unsafe conditions for cyclists.

"Sand doesn't stay where it is all the time. If they put a concrete walk here, it's guaranteed to blow on it. We're just concerned about the convenience, about the ability to get onto the beach properly; it's really a safety issue," Iori said. "We're gonna have scooters, we're gonna have electric bikes, regular bikes and it's such a small length and people come flying by and kids will step out to go to beach and get run over. You're creating a tremendous hazard."

Streetsblog asked the Army Corps about sand on concrete as a potential hazard, but has not received a reply.

The Parks Department controls the section of the beach in question, but without a walkway it’s not as accessible as the sections to its east. Currently, mobi-mats on top of the sand lead beachgoers down to the water at 131st, 135th, 142nd, and 147th streets, which is where the Army Corps wants to install the ramps.

The current president of the homeowners association, reached after initial publication of this story, said he doesn't want the proposed walkway at all, arguing it's narrowness wouldn't provide any benefits to the public, and instead wants to see non-permanent structures, like the mobi mats, on the sand now to help people access the water.

“I prefer not permanent, hard structures, but more flexible and cheaper — think of mobi mats, enhanced," said Paul King.

When the city was building the public boardwalk in the 1900s, it didn't cross into the neighborhoods of Neponsit and Belle Harbor, because of the private ownership of that section of the waterfront. The city declined to extend it unless the property owners agreed to foot the bill, according to a clipping from the Brooklyn Daily Times. The Parks Department later acquired that stretch of beach in various parcels between 1911 and 1947, according to an agency spokesperson, who said that after Sandy, the Parks Department and FEMA rebuilt the boardwalk, but did not build it beyond 126th Street due to "considerable opposition" from the community.

One former Belle Harbor resident, who now lives in Seaside, told Streetsblog that he’s not surprised by the opposition to connecting the community with the rest of the peninsula.

"I am part of the LGBTQ community, and growing up in Belle Harbor was isolating. It’s pretty obvious to me, growing up over there, it’s very white, and secluded in a lot of ways," said Matthew Horgan. “I always wondered why the boardwalk stopped on 126th street, and then began again at Riis Park. It became clearer to me that it was not an accident, but rather by design to keep the community isolated from the rest of the peninsula."

Horgan, who writes his own blog, Sustain Everyone, which explores how marginalized communities are disproportionately affected by environmental burdens, said he supports the ramps and the boardwalk as "a small step toward more accessibility."

The parks committee of Queens’s Community Board 14 passed a resolution last month approving the project, but Iori dismissed the action as irrelevant.

“The community board is a small body of people. They’re not particularly focused on what's going on, and when it comes to having a meeting of seven or eight people that are on the subcommittee, of which none of them live here ... nobody spoke up,” Iori said.

CB 14 did not respond directly to Iori's comments, but told Streetsblog in an e-mailed statement that the "full board did not vote on this item, the presentation was to the Parks and Public Safety committee only."

The federal government, together with the city’s Parks Department — which will be tasked with maintenance of the boardwalk once it is completed — are trying to secure a contract for construction to start by September. Iori says the homeowners association, along with other members of the community, may sue to stop the project.

“It may go that way, we’re very much looking into that. Let’s get the attorneys out,” he said.

City Hall says it fully supports the ramps and the boardwalk extension.

“Protecting our shoreline from the effects of climate change is necessary to create a resilient future for our city," said Laura Feyer, a spokesperson for City Hall. "The Army Corps’ project will strengthen the area while following the requirements set forth by the Americans with Disabilities Act, and we fully support their efforts."

This story has been updated to include background from the Parks Department, as well as quotes from Paul King, the current president of the Belle Harbor property owners association.