It’s deja-vu on Fifth Avenue.

A long-delayed plan to turn a stretch of Manhattan’s most famous avenue into a thru-traffic-less roadway to speed up buses may still be in the works, but the Department of Transportation won't know until late summer at the earliest — which means any implementation will be a whole year after it was initially promised.

DOT reps updated Community Board 5’s Transportation and Environment Committee on Monday night about the transformation of Fifth Avenue between 59th and 34th Street [PDF] — by which we mean there are no updates on the busway.

“We don’t have an updated proposal. ... We hope to present to the Community Advisory Board and CB5 again in August and then move forward with implementation in September,” said DOT’s Kimberly Rancourt on Monday, more than a year after Mayor de Blasio announced the Fifth Avenue busway, promising it would be installed by last summer.

Rancourt added that DOT is moving forward with its installation of a curbside protected bike lane this summer, but as far as the original busway proposal goes, the agency is evaluating "potential modifications, turn restrictions...required turnoffs, and changes to curb access" after initially proposing a real 14th Street-style busway with a requirement that drivers make the first right turn off the roadway so that buses would not be affected by car-caused congestion.

"We’re looking at busway restrictions, and still working on evaluating," said Rancourt, adding that the agency is conducting "additional outreach over the summer."

On the plus side, the bike lane and curb extension part of the plan looks like it will be completed by the fall — if the city can obtain enough green paint (no, seriously).

“The goal is to be done by October,” said DOT’s Ted Wright. "Right now our biggest contractor can’t source green paint, so that changes everything."

The whole process seems to be playing out in slow motion: Last summer, DOT capitulated to the needs of luxury retailers who bemoaned the busway because they wanted shoppers to be able to drive directly to their storefronts along one of the world’s most expensive streets, in favor of the 110,000 people daily who rely on one of the corridor’s 60 to 160 hourly buses. Most of those bus passengers are people of color, and the average income of a city bus passenger is $28,455 a year.

DOT's Manhattan Borough Commissioner Ed Pincar cited the needs of fancy retailers over those long-suffering bus riders — with words that steered away from the de Blasio administration's promise of "a recovery for all of us."

“One of the real concerns we’ve heard so far about a busway with private vehicle restrictions is its impact on retail, in particular during COVID recovery," Pincar said. "And that is something that is being looked at very carefully." [That comment had another irony: DOT almost always hails bus improvements as being good for retailers.]

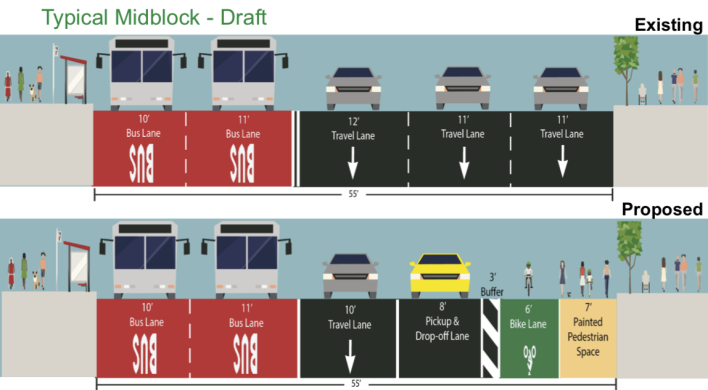

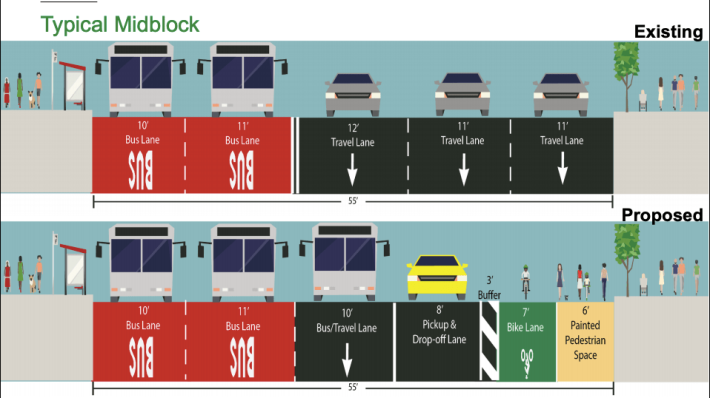

DOT’s original plans showed more attention to the needs of bus travelers, who already benefit from having two dedicated bus lanes on Fifth Avenue. The DOT plan would have added a shared bus and car travel lane, a pickup and dropoff lane, a protected bike lane and wider sidewalks for shoppers — but it was then watered down into a so-called “Fifth Avenue Complete Street,” which instead converted that shared bus lane into a regular travel lane for private vehicles.

Rancourt says DOT still has to meet with corridor stakeholders, including St. Patrick's Cathedral and the business-booster group the Fifth Avenue Association, whose concerns about the busway are exactly the same as they were last summer — they claim a car-free corridor and turn restrictions would hurt noted Mom-and-Pop retailers such as Armani, Dolce and Gabbana, and Tiffany and Co.

Jerome Barth, president of the Fifth Avenue BID, appeared to want the next mayor to deal with the issue rather than the current one.

“Fifth Avenue is a major economic asset to the city,” he said. "This proposal has significant potential to impact the economic recovery of an important corridor [but] it is not well thought out. The businesses on Fifth really believe this project is going to be detrimental to their ability to come back. Making a snap decision that could impact customer access could also impact our ability to bring back the jobs that the city needs. It might be wonderful to potentially speed up travel speeds on Fifth Avenue, but if the jobs are not there in the first place, what’s the point? We believe the priority should be to let the pandemic pass, let the avenue recover and then engage in a meaningful plan for improvements.”

And others raised familiar privileged concerns, including the alleged lack of enforcement on cyclists. The same question might be raised about enforcement against car and truck drivers, who have caused 495 reported crashes on the strip since January, 2019, injuring 25 cyclists, 18 pedestrians and 62 motorists, according to city statistics. Cyclists have injured zero pedestrians in the same period, according to the same city statistics, despite the continuous bike boom. And prior to the pandemic, Fifth Avenue had the highest ridership on a Manhattan corridor without a bike lane, according to DOT.

Others worried about the city's economic recovery, basically saying that the needs of people to drive to Fifth Avenue to pick up a new diamond are more important than those who rely on the bus to get to work.

"I find side streets really clogged, I just don't see how if we force through traffic for people that take clients to shopping sprees on the avenue, to make them turn, there's even no way to turn, which will further clog the avenue. I don't think this will be successful," said Ruediger Albers, who, according to his LinkedIn, is the president of WEMPE, "one of the world’s largest purveyor of luxury timepieces and fine jewelry."

But safe-street advocates countered Albers's argument, saying what the city needs is a safe and efficient public transportation system that works for all, not just the one percent.

"I'm a big supporter of all the elements here of this plan. I'm a big, big believer in busways, it works fantastically on 14th Street," said Paul Krikler. "I would get on a bus much more if I could get through quicker, it's what we should be doing as a city to encourage public transportation."

The committee ultimately did not vote on the measure, punting its purely advisory recommendation until next month.

CB5 Transportation Committee want to refuse to hear any more bike lane discussions until DOT comes back with answers to their long standing concerns about “pedestrian safety issues” from bike lanes. Dragging NYC rapidly backward into the 20th century. Unbefuckinglievable.

— @paulkrikler 🚲🛴🦽🚠🚂 (@PaulKrikler) June 22, 2021