A pair of state legislators have decided it's time to bridge the MTA's bike gap.

State Sen. Alessandra Biaggi of the Bronx and Assembly Member Jessica Gonzalez-Rojas of Queens revealed a new bill on Monday that would establish a pedestrian and cyclist advisory committee inside the MTA, so that people-powered transportation has some representation at a transit agency that critics say has no interest in the most sustainable transportation mode on bridges that exclusively serve the least.

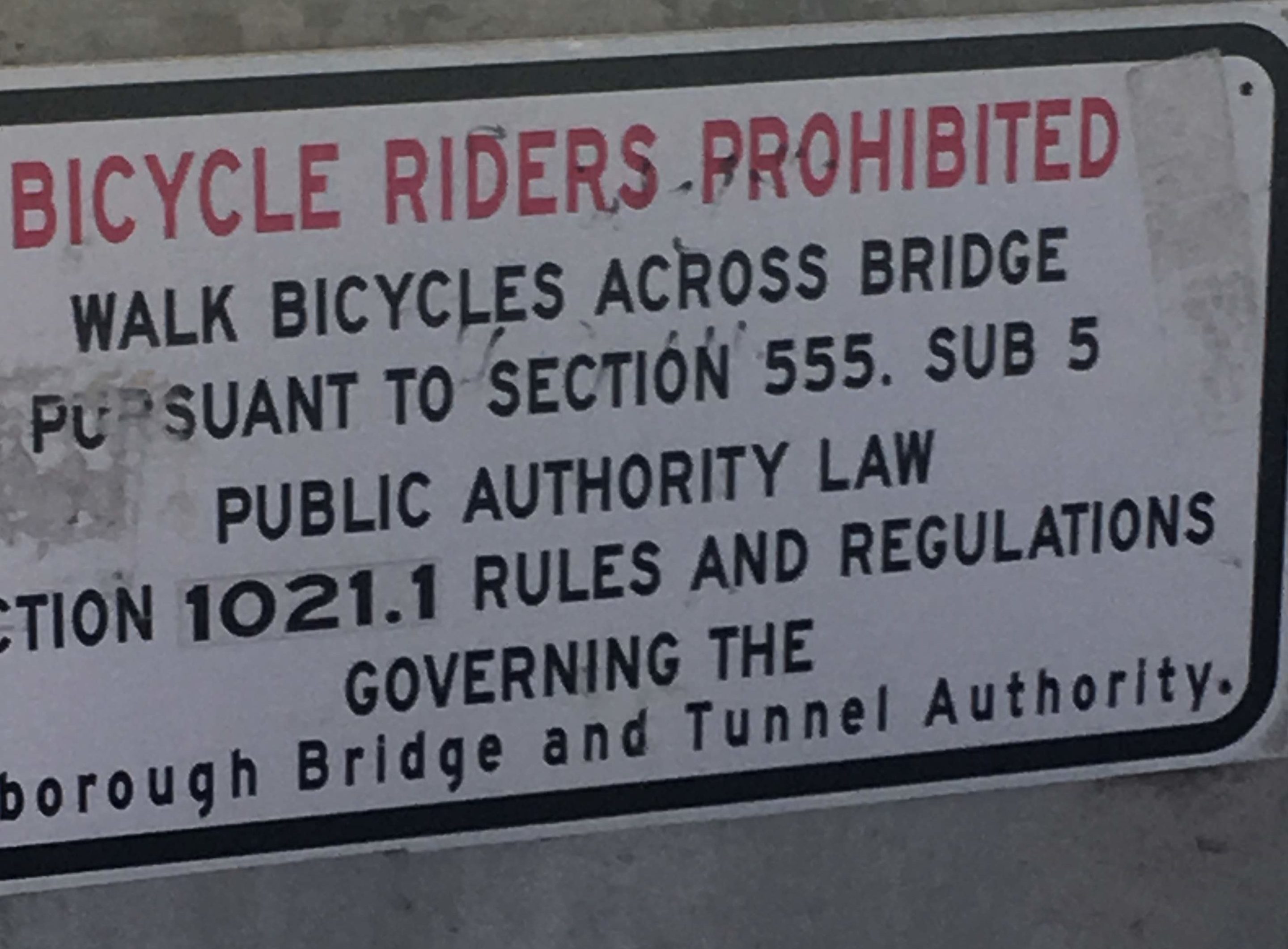

"Despite the rapid growth of bicycling in New York City over the last decade, the MTA has done little to improve bicycle access at its stations and prohibits cycling on its bridges altogether," said Biaggi. "As more New Yorkers have turned to cycling and outdoor spaces throughout the pandemic, we must continue to make our communities welcoming to cyclists and pedestrians and encourage residents to use clean forms of transportation."

The bill from the pair of lawmakers would establish a 13-person advisory committee that studies and makes recommendations around cycling and pedestrian access on MTA bridges and passenger stations. Per the law, seven members of the committee would be appointed by the governor, two each by the Senate majority leader and Speaker of the Assembly and one each by the minority leaders in each chamber.

"This legislation will create a mechanism by which we can ensure to improve the access to New Yorkers who want to cycle on MTA bridges by bringing diverse stakeholders to the table,” said González-Rojas.

The MTA's relationship with cyclists has in the past made it seem like the authority's acronym actually stands for Must Trash All, when it comes to cyclists. It's still illegal to ride your bike across MTA bridges (the ones with bike paths, even on the 10-foot wide pedestrian path on the Cross Bay Bridge), and the MTA Police (or state troopers camped out at the base of the Gil Hodges Bridge) have not been shy about handing out tickets for violating the ban.

And despite a growing chorus of voices calling for a bike lane on the Verrazzano Bridge, the MTA has stuck by its historical refusal to consider anything but the most expensive, dead-on-arrival, falsely contrived option in order to avoid having to build the bike path or even take one of the span's 13 motor vehicle lanes.

The authority's attitude towards bikes on commuter trains is also one of outright malice. Metro-North and LIRR riders need to carry a bike permit around with them in order to bring a bike on the train, secure bike parking doesn't exist at train stations and there are endless restrictions on which trains you can even ride with a bike. All of this hostility has advocates thrilled at the possibility of finally having a way to be heard at the MTA.

"Right now people doing petitions are just shouting into a void and aren't on the MTA's radar, so we need something real," said Bike New York Director of Communications and Advocacy Jon Orcutt. "And this is a good way to invade the MTA's policy, budgeting and planning space, because they're not going to come to this on their own."

The MTA declined to comment on the bill. In March, 2020, CEO and Chairman Pat Foye said the authority would "consider" temporarily ending its cycling ban to help commuters who were wary of packed trains. But no action was taken since then while cycling exploded across the city. That lack of movement is the exact kind of thing that Orcutt thinks the cycling/pedestrian council could change.

"We tried to get some officials about a pilot summer relaxation of the rules against cycling on the Triborough Bridge a couple years ago, but there's no one home, no one to talk about it," he said.

According to Orcutt, the MTA lags far behind the Port Authority and state DOT in terms of even understanding that bikes are a form of transportation that exists. He noted that the Kosciuszko Bridge and the Goethals Bridge were both rebuilt with well-reviewed bike paths. The Port Authority has also embraced secure bike parking at its stations, in the form of an Oonee pod at the Journal Square PATH stop.

"The other piece of this is bike parking at stations," said Orcutt. "The most sustainable transit systems tightly integrate bikes and rail and and we have a plurality of the rail in the United States in the region and we're not doing this. The MTA owns land around some of their stations in the suburbs, so if it was interested in that, it would make a difference."

Unlike those agencies, Orcutt said the MTA reacts to bike infrastructure as some kind of invasive species, highlighted by the ways it sabotages ideas like a Verrazzano Bridge bike lane by only suggesting complicated and expensive engineering boondoggles to complete the task. But with a possible lower deck reconstruction for the bridge slated to happen sometime in the next decade, Orcutt said the potential legislated advisory council can ensure cyclists and pedestrians finally get a path to Staten Island.

"When the State DOT did the Kosciuszko Bridge it didn't have a separate line item. When the city rebuilt the Williamsburg Bridge it didn't call out the bike lane as some kind of add on. A bike and pedestrian path should be the cost of doing business when fixing a bridge in 2021. And a Verrazzano Bridge bike lane would have massive ridership, if only because it's fun," he said.