The city should shift its strategy for reducing excess driving by Uber, Lyft and other app-based cab companies to simply charging 11 cents for every minute that a cab is driving or sitting around empty, a new Council report argues.

The Council study, "Curbing For-Hire Vehicle Stockpiling in the Manhattan Core" [link] says that instead of trying to reduce the overall percentage of time that app-based fleets are "deadheading" (i.e. driving around or merely sitting empty before or after transporting a customer), the city should use a flat per-minute fee of 11 cents per cab during peak hours and 5.5 cents during off-peak or weekend times in Manhattan south of 96th Street.

The study was prepared by mobility expert (and Streetsblog contributor) Charles Komanoff — and it's no surprise to readers of Streetsblog. Last year, after Manhattan Supreme Court Justice Lyle Frank threw out a Taxi and Limousine Commission proposal to reduce the percentage of time that app-based cabs could be cruising from 41 percent to 31 percent, Komanoff confirmed that he was working with the Council on a different approach because "a charge on idle time is bound to be more effective than a [percentage] cap in combating Manhattan gridlock, as well as fairer to riders."

A new per-minute fee would be better than the TLC's percentage cap, the Komanoff report argues, because:

- Congestion would be cut more dramatically with an actual fee. The report argues that Manhattan travel speeds would increase by 2.7 percent more than what is expected once congestion pricing kicks in for all drivers; under the TLC proposal, those speeds would only increase by .7 percent.

- The fee is easier to monitor with existing technology; the TLC proposal had left too much of the calculation up to the tech companies.

- Reducing gridlock would have a societal benefit of $160 million in regained productivity, again about four times what the TLC had anticipated.

- The charge itself would generate $80 million per year for the city.

- The fee could be adapted to cover delivery companies at some point (though there is pending state legislation that would slap a $3 fee on all non-essential online orders).

It's unclear if Komanoff's proposal will become law, but Council Speaker Corey Johnson called his findings an "excellent report, which is an important contribution to the policy conversation about reducing gridlock and improving transportation efficiency in New York City.

“I am confident that Komanoff’s findings will pave the way for more effective transportation policy-making in New York City and I look forward to having a public conversation about the per-minute charge,” Johnson added.

The TLC was motivated to address deadhead cruising because app-based cab trips account for close to one-third of all Manhattan traffic. And here's why: According to the city, 60 percent of a typical taxi trip in the Manhattan core comprises waiting for a pickup notification and traveling to the pickup itself. That's a lot of empty driving or standing, causing a lot of unnecessary congestion.

Ride-hail companies keep so many empty vehicles on hand so that customers can get a cab within minutes of firing up their Uber, Lyft, Via or other cab app.

“They want to keep ridership times very low and flood everywhere with cars, but a large portion of cars are empty," Deputy Mayor Laura Anglin said in 2019 when she announced the TLC proposal to require the tech/cab giants to use their existing technology to reduce deadheading from an average of 41 percent to 31 percent. (The city is still considering appealing Judge Frank's ruling, though in the meantime, the Council may act.)

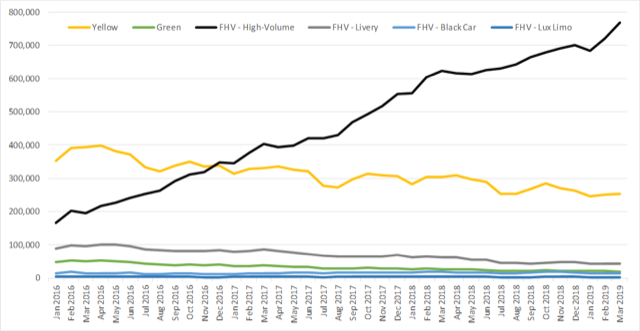

Neither the Council report nor the TLC proposal affects yellow cabs because their numbers are capped by law at around 13,000 vehicles. By comparison, there are close to 100,000 app-based cabs, or "high-volume for-hire vehicles" as the city calls them, which carry the vast majority of the estimated 1.1 million cab rides per day (see chart below).

There is already a surcharge attached to all for-hire vehicle trips in Manhattan below 96th Street. Since February, 2019, yellow cab customers have paid a $2.50 surcharge and app taxi customers have paid $2.75, a fee that is sort of a cab congestion pricing toll in that the estimated $35 million a month that the fees raise is funneled towards public transit.

Other cities also have surcharges attached to ride-hail services, which have been shown to reduce transit use. But the Komanoff proposal appears to be the first time a city would charge an additional fee to reduce the congestion that stems from all those empty vehicles.

The 11-cent figure is built from Komanoff's years of studying traffic patterns and the cost of congestion. Here's how he derived it: Once congestion pricing kicks in, auto drivers into the central business district will be charged a toll, which is expected to be about $13. That price, the report says, is roughly 14 percent of the total cost of traffic slowdown that each of those auto trips imposes on other drivers overall. Komanoff also estimates that a minute of an Uber or Lyft sitting in Manhattan south of 96th Street imposes around $.80 of delay costs on other drivers. Fourteen percent of that figure would suggest a per-minute fee of 11 cents. Hence, the 11-cent-per-minute fee.

"This empty-time charge would not penalize ride-hail companies for their vehicles’ empty time but rather address and mitigate the costs resulting from that time," the report states.

The per-minute charge won't be applied to yellow cab owners for a simple reason: they've already paid the city plenty.

"Taxi owners and drivers have invested equity by purchasing medallions, in return for which they gained exclusive franchise rights — until those rights were breached by the advent of ride-hail services," Komanoff said. "An ancillary benefit of the empty-FHV charge is that it restores part of the lost equity."

Given an 11-cent-a-minute (or $6.60 per hour) charge, Komanoff estimates that if the app-based companies pass on the entire idle-time costs to their customers, the result would be a $1-per-ride fee during peak hours or as low as 30 cents in off-peak hours. That fee "may nudge the takers of some of those trips to substitute other means — subway, bus, bicycle, or a closer destination — for trips in the Surcharge Zone currently made in ride-hail vehicles," the report suggests. And that nudge would go to yellows or to fewer Uber and Lyft trips overall.

Plus, the tech giants would be incentivized to alter their algorithms to lower their costs, which would reduce congestion, he added.

So is Komanoff right? Well, on the central issue — combatting congestion — there is broad agreement that something needs to be done.

"The question in my mind is which approach better makes the companies manage the efficiency of their fleet," said longtime taxi industry expert Bruce Schaller, a former city DOT official during the Bloomberg administration's initial effort to approve congestion pricing.

But Schaller focused on the "nuances" of any plan to mitigate congestion.

"For example, prior to midday, there is naturally an overabundance of drivers in the central business district because there are more dropoffs than pickups," he said. "After noon or 1 p.m., it's the reverse. The latter is easier to control since the companies could give disincentives to coming into the zone. In the a.m., the task is to get drivers out of the zone."

What's the best way to do that? It's unclear.

"The advantage of the [TLC's percentage] mandate is the regulation specifies the desired outcome and holds companies to that," Schaller said. "Since no one has done anything like either approach, it's hard to evaluate a statistical model which naturally requires making assumptions about human behavior."

Curbing FHV Stockpiling in Manhattan Core by Gersh Kuntzman on Scribd