Gov. Cuomo launched his indefinite, four-hour overnight shutdown of the New York City subway — the first such ongoing closure since the system opened in 1904 — as an emergency measure on May 6 in order to disinfect the trains nightly against the spread of the pandemic.

By now, however, the nightly subway shutdowns amount, in effect, to something much different: a systematic, racially disproportionate assault on the livelihood and economic position of the city’s Black and brown communities, especially of its essential workers.

Cuomo may not have intended the shutdowns to have that effect — but that is the upshot. News that overnight service won't return until at least next summer is unacceptable (especially given our better understanding that COVID-19 transmission in the transit system is not the problem that many thought it would be). Cuomo must end the shutdowns — now — especially as he mulls adding insult to injury, in the form of a 4-percent transit-fare hike, which the Metropolitan Transportation Authority Board may vote on as early as next week.

The shutdowns are undermining the livelihood of the city’s working classes and communities of color — creating untenable situations for many essential workers in which they must spend inordinate amounts of time commuting, waiting for buses that don’t even begin to replace the missing trains and that don’t respond to the commuting patterns forged during the pandemic. Plus, the limited capacity and infrequency of the replacement buses could lead to crowding — which could help spread COVID!

In a recent paper, I calculated the average extra commute times for workers on the replacement routes — and the routes’ capacity. For inter-borough trips, the buses added one to 71 minutes to each trip, for an average of an extra 19 minutes, or a 40-percent increase in trip time. For intra-borough trips, buses added four to 60 minutes to each trip, averaging another 23 minutes, or an almost 70-percent increase in trip time!

According to the MTA, the three replacement routes run every 20 minutes, for three buses an hour on each line. The buses have only 40 seats each, meaning that each route may transport only 120 passengers an hour. If social distancing is enforced and every other seat is left unoccupied, that brings the maximum capacity of each line to only 60 people per hour. The subway, of course, can carry multitudes more workers overnight — which will be necessary for any real economic recovery.

Interestingly, as anyone can see, the MTA still is running many empty trains at a fair frequency through the system every night during the shutdown hours.

That’s why it’s time to end the pandemic-induced shutdown experiment before it does any more damage to workers — and resist any budget-related attempts to make the situation permanent. The most vulnerable New Yorkers must not be so sacrificed.

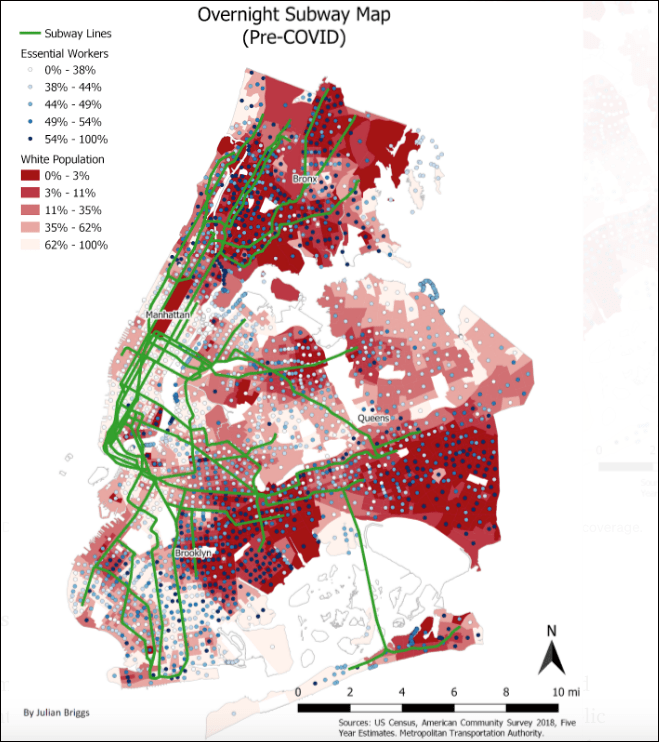

A map that I created with census data clearly tells the story of this injustice: On the map, darker red census tracts represent those containing more people of color (fewer White residents) and lighter red represents fewer people of color. The map also measures the number of essential workers per tract, using occupational data downloaded from the Census website, including food services workers, healthcare/education workers, and transportation/warehouse/

When the two datasets are overlaid, a correlation between race and occupational status becomes clear. Darker blue dots are more concentrated in darker red areas, and lighter blue dots are mostly found in lighter red areas, meaning that people of color are more likely to be essential workers, and therefore rely on the subway system more than white non-essential workers, who are more likely to be able to work from home. That communities of color bear the brunt of the pandemic does not represent new information, but the data visualization shows just how strong the correlation is.

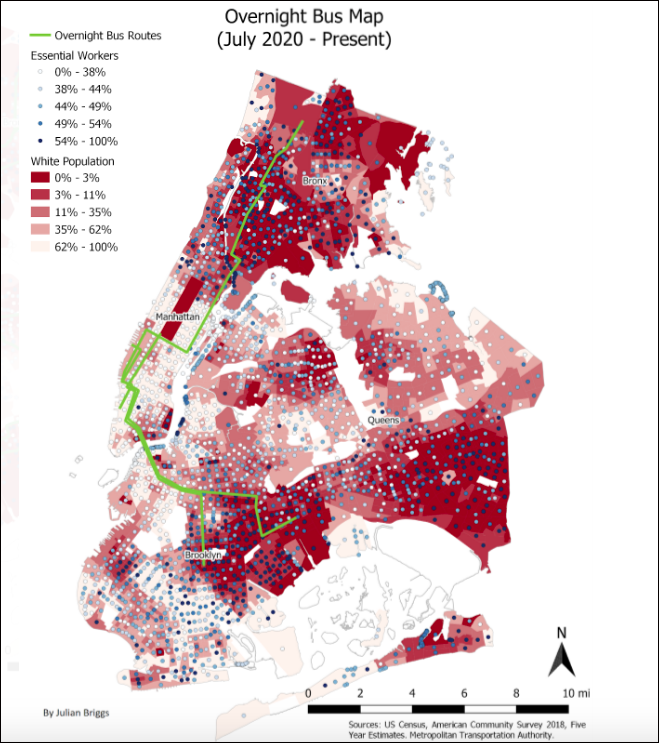

The dispersion of essential workers seen in the map demonstrates just how grossly inadequate — even punitive — are the replacement bus routes. As the MTA website shows, all three bus routes originate in Manhattan. One goes to the Woodlawn in the Bronx (Bx99) paralleling the No. 4 train, and two go to the Brooklyn — terminating at Midwood (B99) and East New York (M99), paralleling the 2 and 3 trains.

For my final GIS project I mapped out how the nightly @MTA subway shutdowns disproportionally affect POC and essential workers across NYC.

— Julian 🚇 🐝 🪩 (@julestrainman) December 10, 2020

My maps compare the coverage of the subway vs the replacement buses, overlaid with racial and occupational data. pic.twitter.com/2b3ooBAh8y

This very limited coverage area omits the eastern Bronx, southern Brooklyn, the Upper West and Lower East sides of Manhattan, and the entirety of Queens from the overnight service. Buses form the backbone of transit in Queens, with most feeding into the subway system at some point for a relatively convenient transfer. The elimination of all inter-borough transit to and from Queens overnight basically cuts off the borough from the rest of the city.

The whole scheme shows a callous disregard for the safety of the New Yorkers who risk their lives every day to keep our society functioning.

As the governor and MTA contemplate their next budgetary move, they must reinstate the overnight subway service that workers so desperately need.

Julian Briggs (@julestrainman)is an undergraduate student at Columbia University's School of Engineering, studying civil engineering and concentrating on transportation planning.